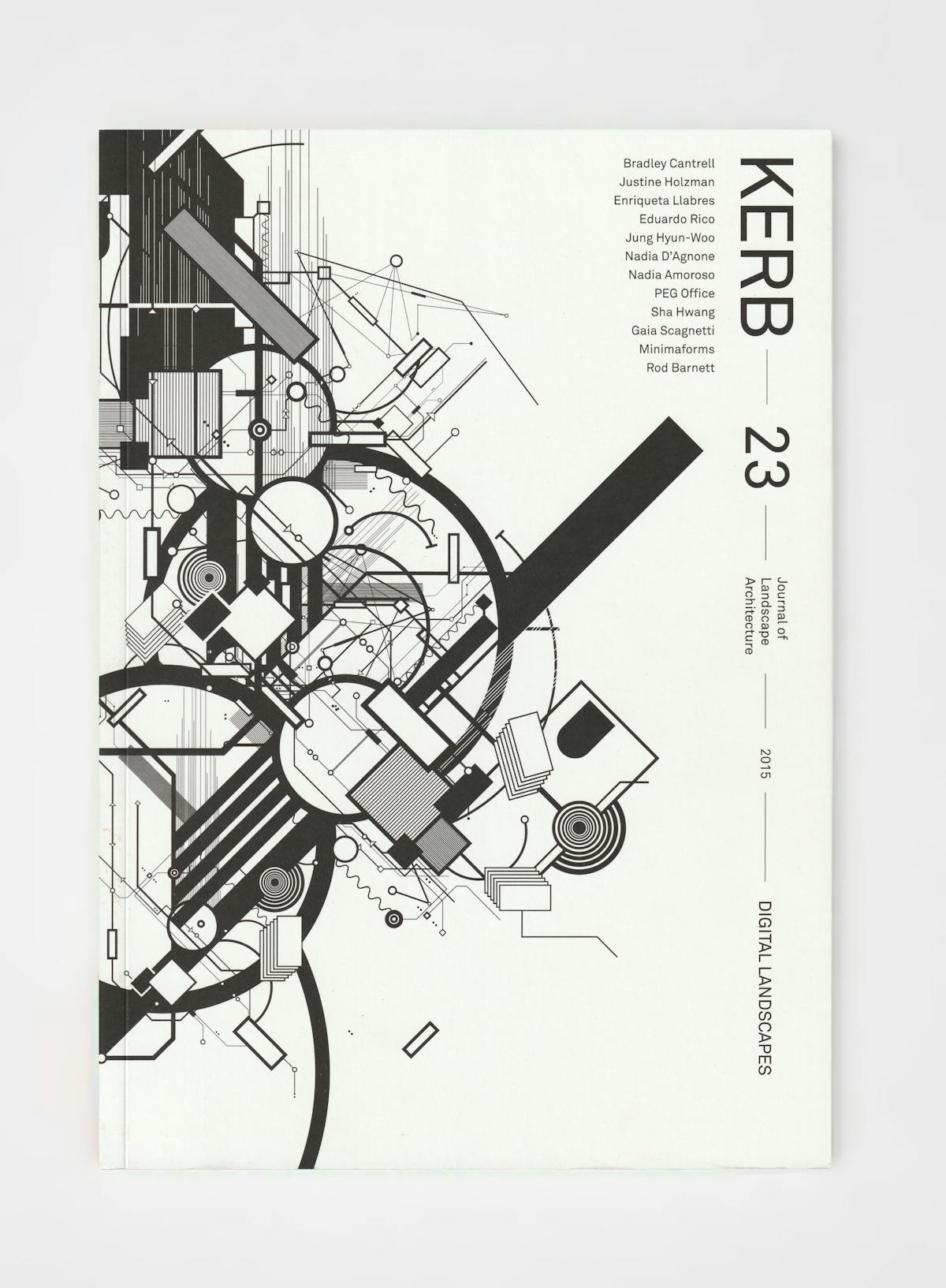

Digital Landscapes is the ecology that is driven by, and drives the alterations that are reflected by the landscape. The alterations on the built environment are the translation and manipulation of information and matter where the interaction between the physical and the digital drives the landscape’s behavioural qualities as matter forms and reforms. The landscape is positioned not as material ground but as an ecology, an assemblage of interacting layers, often remaining latent, waiting to be discovered and decoded. Thomas Mical explores how each location is an ‘array’; a space of innumerable behavioural variations that assume the possibility or impossibility of successfully employing design processes to augment the reflection on the landscape. This approach to the ground is also reflected in the digital landscape that it parallels; as Joe WT Scott notes,

‘[we experience] the real fear of the infinite in a world we rely on, yet we only glimpse the polished surface of via a screen.’

The surface is the outcome of constant evolution of matter and material that makes up the layers of the landscape: consequently, the landscape emerges from the digital landscape’s ongoing adjustments that maintain balance between ‘chance and control’. Scott likens layers of matter forming and reforming to the sublime. These layers show a vast and fearfully endless landscape that has infinite possibilities, and represent a resource for inventing our world without the stagnant matter and materials we reuse. However, Bradley Cantrell and Justine Holzman argue that this exploration of two distinct spaces – virtual and reality – is becoming invalid. Digital and landscape are no longer separate resources. They move us on from associating the digital with technology, and usher us towards the idea of a new perspective on digital landscapes.

As both physical and digital continue to alter and evolve into each other, Rod Barnett infers that we can only properly attempt to understand the change as we develop modes of interaction through the necessity of invention. This stems from the need to not only improve, but invent better quality of life, which comprehensively, reorients design informs design. In this way, substance and form are brought about through recognition of matter yet to be decoded.

Substances are nothing other than formed matters. Forms imply codes, modes of coding and decoding.1

In landscape architecture, identifying matter is linked to simulation. Two main forms of simulation arise: ‘Identification of Idea’ and ‘Identification of Information’. In Experiencing Information, datum-visualisation introduces us to the literal imposition of data onto the surface in order to alter landscape experience. This landscape experience becomes the design of the surface, as the visual element is not a reflection of the landscape, but an interpretation of information.

Identification of Idea stems from the process of unpacking matter, where simulation is generative and speculative. Through visually recreating an existing condition, this unpacked and translated matter is used to anticipate conditions which aid design. PEG Office uses simulation as a generative and speculative process through digital mapping to better understand the existing conditions they aim to alter:

‘this can enable designers to expand beyond our profession’s overreliance on illustrating change – rather than working with it … Variability and change are built into the thinking behind simulations, and reflect the variability inherent to the systems they characterize.’

Simulation decodes the landscape by unpacking the layers of information that form landscape conditions. These layers are infinite and our access to them is limited only by the tools we have available to extrapolate information.

Abstraction allows us to test new connections, through the use of tools, in search of undiscovered outcomes. Now, more than ever, the tool can dictate the information and connections made in the landscape. Sha Hwang and Gaia Scagnetti suggest that the tool itself holds agency as ‘successful tools alter the DNA of entire populations, through cost, materials, or even cultural attitudes around aesthetics.’ The ways in which tools are used is how they alter the landscape, but are limited by the way we approach them. The paper ‘Digital Tools of Multiplicity’ similarly describes that tools act solely as a mediator — they are generative in that they allow for ideas but do not generate ideas.

‘Tools that help us observe and interact with live processes foster the emergence of intuitive forms of engagement with matter and human agency over it. Digital tools are explored through their capacity to shape the world, and through their influence on data recording and visual representation.’

Brian Davis considers how tools can enable visual communication by looking at how tools can move beyond reappropriating analogue processes and their subsequent outcomes and ‘reveal and construct relations that are otherwise hidden or latent.’ But it is the use of the same tools that allow us to extrapolate data, simulate conditions with more accuracy, and even speculate historical and behavioural information. This historical and behavioural information is quite often left out when digitally abstracting information, as most information is from the physical components of the landscape. However, David Mah uses the narrative of the Manhattan’s Commissioner’s grid, and abstracted hydrologic and topographic information, to unveil latent matter and triggers within the site that enable us to imagine an alternative Manhattan.

Historical information is not limited to speculations or in depth abstraction. Minimaforms seek to create new forms of communication and interaction by bringing behavioural information to life. Projects such as Petting Zoo and Memory Cloud encourage this creation of communication between people, and between people, machines and the landscape. Usue Ruiz-Arana’s installation adds behavioural matter into the landscape, allowing us to engage with a ‘mundane city,’ and to explore how adding a non-physical component into the landscape can alter the way it is approached and perceived. The installation gives way to a new translation of space that exists beyond just the surface. It allows a response, decoding and translating new layers of communication and interaction.

Transformation and invention are inseparable functions: both are quality producing processes that describe the coherent flow of matter through time and it is time that makes the new both possible and necessary.2

Viewed as the infinitely complex relationships existing in a singular location and beyond a ‘digital ecology’, the nature of Digital Landscapes eludes the processes of categorisation and organisation. Technological advances continue to expand cognitive boundaries and little excuse for simplification remains. Increasing accessibility to the layers of information provides us with a renewed appreciation of the power of abstraction to assist us to attain clarity and purpose of outcome.

The ground as an outcome of ecology is a reflection of our generative approach to the landscape using simulating, fabricating, and augmenting as techniques to decode and translate the landscape and its functions. These processes together form a digital ecology that impacts the way the landscape is approached and altered in the quest to find necessary meaning in new forms of communication and interaction. Digital and landscape are reflections of the infinite ecologies that coexist and surround us. One is often the surface of the screen, and the other is the outcome of the ground: both are the polished surfaces which allow us to catch a glimpse of something we do not always fully understand. The surface of the screen, and the outcome, are never static.

There runs an invisible thread that binds one living being to another for a moment, then unravels, then is stretched again between moving points as it draws new and rapid patterns so that at every second the unhappy city contains a happy city unaware of its own existence.3

The alterations to the digital landscape are the ways in which we attempt to decode and translate matter and information that is permanently connecting and interacting with the components of the landscape. Through exploring digital landscapes we can derive a better understanding of the ecologies that shape the world. That understanding can assist our search for insights into how we can dictate change.

Footnotes

-

Gilles Deleuze, 1987. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. 1st Edition. University of Minnesota Press. ↩

-

Sandford Kwinter, 2002. Architectures of Time: Toward a Theory of the Event in Modernist Culture. Reprint Edition. The MIT Press. ↩

-

Italo Calvino, 1978. Invisible Cities. Edition. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. ↩