The United Nation’s State of the World’s Cities Report 2006/7 indicates that this year the world will enter ‘a new urban millennium in which the majority of its people will live in cities … “Metacities” massive conurbations of more than 20 million people [will emerge in] Asia, Latin America and Africa … [and] the majority of urban migrants will move to small towns and cities of less than 1 million inhabitants … ’1

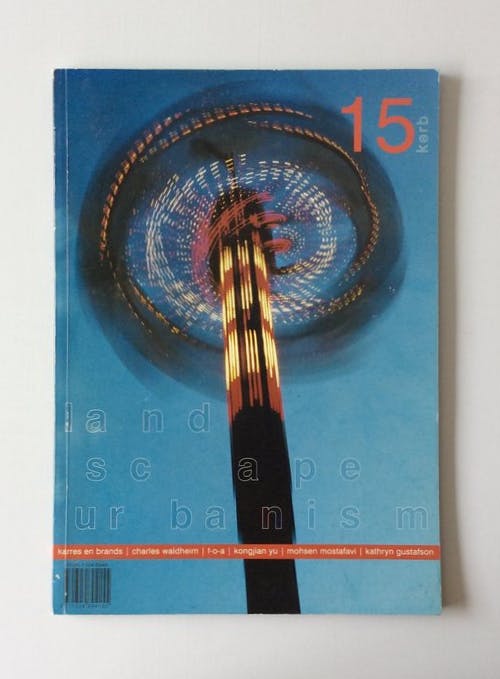

The fifteenth, international issue of Kerb focuses on the theme of landscape urbanism. We have brought together, research laboratory founders, ecologists, urban designers, journalists and activists; students, graduates and academics; leading architectural and landscape architectural practices, as well as the editors of and contributors to the key landscape urbanism publications, The Landscape Urbanism Reader and Landscape Urbanism: A Manual for the Machinic Landscape, to consider how can we reconceptualise the design and growth of future cities?

In an interview for this issue, Mohsen Mostafavi suggests that we can learn from the field of landscape ‘for the purpose of coming up with new forms of urban thinking’. But in considering new types of urban organisation we must also re-consider the idea of landscape and its specific relationship to the human genus. Ideas of nature, landscape or the environment and their representations are perceived as external to human activity. The oppositions of nature and culture, landscape and architecture, are no longer adequate to deal with contemporary urban conditions.

As organisms, we construct the ecosystem of the city, one that is as natural as any other. We are ‘active subjects transforming nature according to its laws and are always in the course of adapting to the ecosystems [we] construct.’2 As David Harvey suggests human urbanisation is one of the most significant of all processes of environmental modification that has occurred in recent history … creating a set of global ecological conditions never seen before.3 If we are to seriously consider new modes of urbanisation in response to contemporary ecological conditions then the architectural disciplines need to further examine the relationships between these varying constructed ecosystems (historically), and the social practices which manifest these conditions.

Landscape urbanism brings with it a multitude of meanings and potentialities; the main point of the discourse does not lie in defining what it is, rather than investigating what it might become. We are always seeking a new understanding, or view, of how things are, as opposed to how they currently appear. In the ever evolving, or adapting processes of our cities, there are many scales where this unfolds. No one view, or scale, is enough to capture this process in its entirety. It may be more obscured on the street level, even if we can sense it, and more easily illustrated laid out in a birds eye view with only a flattened sense of hierarchy.

It’s useful to understand our cities as territories; they are not stable, nor are they inert, but are active processes of organisation. It therefore makes sense in this ‘age of mobility’ for us to strategise in our planning and positioning of projects, in a more anticipatory fashion. However adhering rigidly to this framework, as a type of doctrine, undermines the intention of learning from the temporal and the transitory, in our expanded sense of the landscape. Adaptability is a key word at the moment and most of what landscape urbanism promises is creative and adaptive. The danger may lie in how the ‘flexible’, when built into our planning and strategising, may turn into the ‘generic’ in our public spaces and our cities.

The discipline of landscape architecture needs to reassess its understanding of ecology and shift the discourse from environmental protection and management to one of constructed ecologies where current ecological conditions are examined through an understanding of the social and historical processes of urbanisation. By working in such a way the potential for the architectural disciplines is vast. A failure to do so may mean that the role of the landscape architect remains fixed, working in the traditions of the gardenesque, reinforcing the figure/ ground oppositions of human urbanisation, being exterior to environmental ecosystems.

In reading this edition we would like you to begin by considering landscape urbanism as ‘a projective mode of thinking’.4

Footnotes

-

A Eduardo Lopez Moreno and Rasna Warah, ‘Urban and Slum Trends in the 21st Century’ (online), available from: http://www.un.org/Pubs/chronicle/2006/issue2/0206p24.htm (Accessed: 3 March 2007) ↩

-

David Harvey, Justice Nature and the Geography of Difference, Blackwell Publishers,Oxford,1996 ↩

-

ibid ↩

-

Mohsen Mostafavi ↩