Did we miss it? Is the future here already? While we’ve been buried under this publication we may just have passed that milestone, that turning point of ‘civilisation’ that by many accounts demarcates the beginning of the future. This point, reached somewhere about now for who can really tell, marks the urbanisation of half the world’s population. Most of those will reside in an expected 27 ‘megacities’ (those with more than 8 million citizens) and as many as 11 coastal ‘hypercities’ (more than 20 million) in Asia alone. But the greatest growth will occur within medium-sized cities with a current population of around 500,000. This point also represents the turning point for rural populations which are expected to recede into negative growth at this point. The relationship of cities to the surrounding rural landscape has become so distorted as to induce calls from larger cities for self-government. The Mayor of London claims a greater affinity with New York or even Tokyo than the rest of England.

For some this is the beginning of the end. For others, it is just the start. The city is a test a site, offering the chance to unite people and deal with problems in efficient and effective ways, to liberate people from many constraints and to offer more to the lives of those who dwell in them through economies of proximity and scale. Are we nostalgic for a city which is more than fractured pieces produced through differing ideologies? Cities are sites of layering, they are constantly rewritten and contradictory, with unexpected links or disruptions produced through the informal and the deliberate. This same process of competing interests creates frictions that were evident in our own process of curation — but it has been said that without contestation there is stasis.

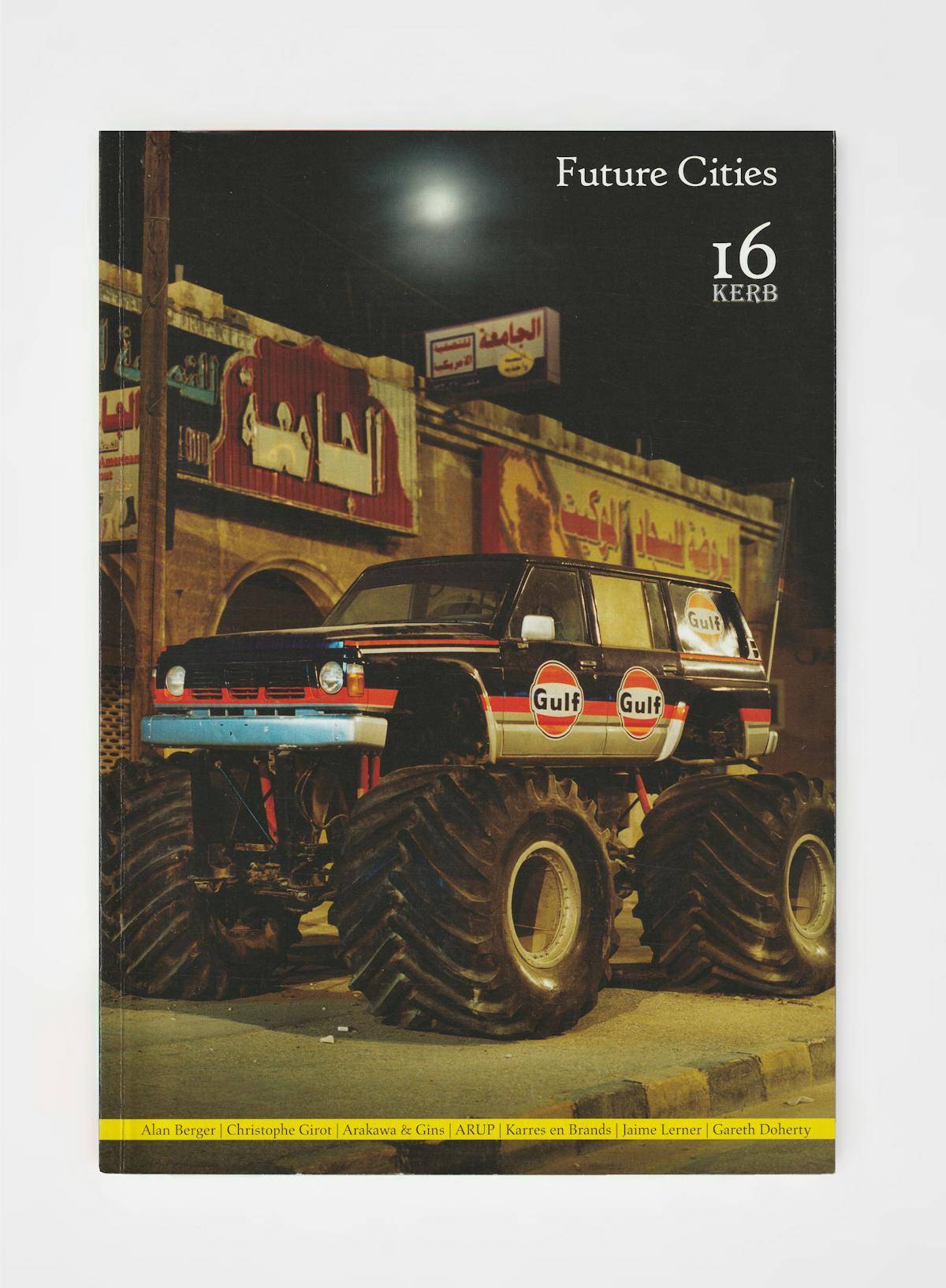

The sixteenth edition of Kerb focuses on the theme ‘Future Cities’. We have collected a diverse range of responses from practitioners, artists, theorists, multinationals and students globally. Although diverse there are obvious threads running through these texts that work to create a collage of ideas much like the physical city.

Landscape is the stage that we play upon, the fabric that clothes us collectively. The dominant globalisation rhetoric suggests that place no longer matters.1 Discourse focuses on the ‘products’ of globalisation (finance, telematics) rather than the processes that make them possible. This is a rhetoric that excludes the increasing majority; the diverse and marginalised workers that embody and are embodied by the city.

Just as great as the divide between developed and developing nations and between cities and their surrounds, will be the increased divide between coastal megalopolises and inland cities. Are current landscape architecture systems suited to deal with this shift from national to regional significance? Does it buy into the dominant rhetoric of exclusion that ignores the processes of the physical city? Charles Eames is famous for the quote ‘design addresses itself to the need’, while Rem Koolhaas asks if the West can criticise the aspirations of developing nations. China builds mega-structures while Africa screams out for infrastructures. As disparities increase, the challenge to design the gradients between becomes increasingly important and challenging. Alan Berger suggests a shift in the predominant role of the landscape architect to one that ‘works on the edges and not the narrowed centre’, the landscape architect must ‘push on the limits of the current discourse rather than trying to resuscitate its old centre’. Berger reframes constraints as opportunity ‘expand[ing] site program and strategy outward, adjusting and feeding-back small scale issues based on large scale logic…’

Shifting in scale, Arakawa + Gins contest the status quo at the level of the body-space interface. Recognising that ‘…the city is an active force that “leaves its traces on the subject’s corporeality”’2 they invite us to step outside accepted paradigms and imagine new possibilities for the space we inhabit. Claire Martin also works at this level. She explores the haptic experience of the post-modern sublime in relation to mortality, she brings death into the city as part of the everyday experience of the commuter. Van Valkenburgh reframes traditional concerns of practice such as the need for open space within the city. He returns to the need of the designer understanding the materials they use and the experiential qualities of built space.

Kate Church embraces global culture not as a homogensing force but as something that also produces difference. She uses the phenomenon of individual customisation, to create a framework to reconceptualise landscape practice, to encourage the appropriation of ‘public space’. Michael Qingsheng He harnesses the ‘humble’ supermarket to design for the forces operating in the superspeed development of Shanghai promoting potentially more economically sustainable development. It is a speculative project shifting the designer’s role in China from working on the iconic landmark to working with multi-faceted systems of urban fabric.

Arup Architect Malcolm Smith discusses with the editors his work on the adjacent island of Chongming, delving into design ethics within sustainable development rhetoric. He argues for the environment as the organising force for ‘shaping a better world’. Judy Rogers questions the indiscriminate use of the word ‘sustainability’ and the emotive minefield that surrounds it. She asks the question: ‘sustainability for who?’ Cities, like ecological environments, are contested spaces. When intervening in ‘natural’ processes we start making value judgments of what should, or shouldn’t, be sustained; ’ … the problem for most of the world’s poor is not that their conditions cannot be sustained but that they should not be sustained.’3 In India Clare Cumberlidge and Lucy Musgrave discuss Himanshu Parikh’s Slum Networking project. Parikh cheaply and efficiently retrofits the basic infrastructure of drainage, sewerage and water supply into informal settlements, providing the basic rights of citizenship to residents.

Map Office, in ‘Breeding Dust’, focuses on the indeterminate, reminding us of the contingency of city development through Marcel Duchamp’s obtuse criticism of Le Corbusier. Duchamp’s interesting play on words is more than just semantics, a subject that is taken up by Bridget Keane in ‘Rethinking the City’. She shows how language is materially productive, verifying publication’s limited yet very real role in shaping the future city through antagonism and stimulus of thought and action.