… here be dragons …

Historically cartographers would denote areas of undiscovered or uncharted territories with illustrations of mythical creatures or dragons.1 This warning gesture symbolises an ingrained fear of uncertainty and renders some people insecure and others curious of the unknown. We believe these same uncharted territories exist today; they manifest in an uncertain future, made ever more uncertain by the fluctuating present condition. Given the unpredictable nature of the future, who will have the capacity to charter these territories and operate within them? To reveal possible answers to this, this issue of Kerb profiles those who are comfortable exploiting the dynamism of the present condition and practising in uncertain realms. Those who are afraid of the dragons, well, they’re not in our journal.

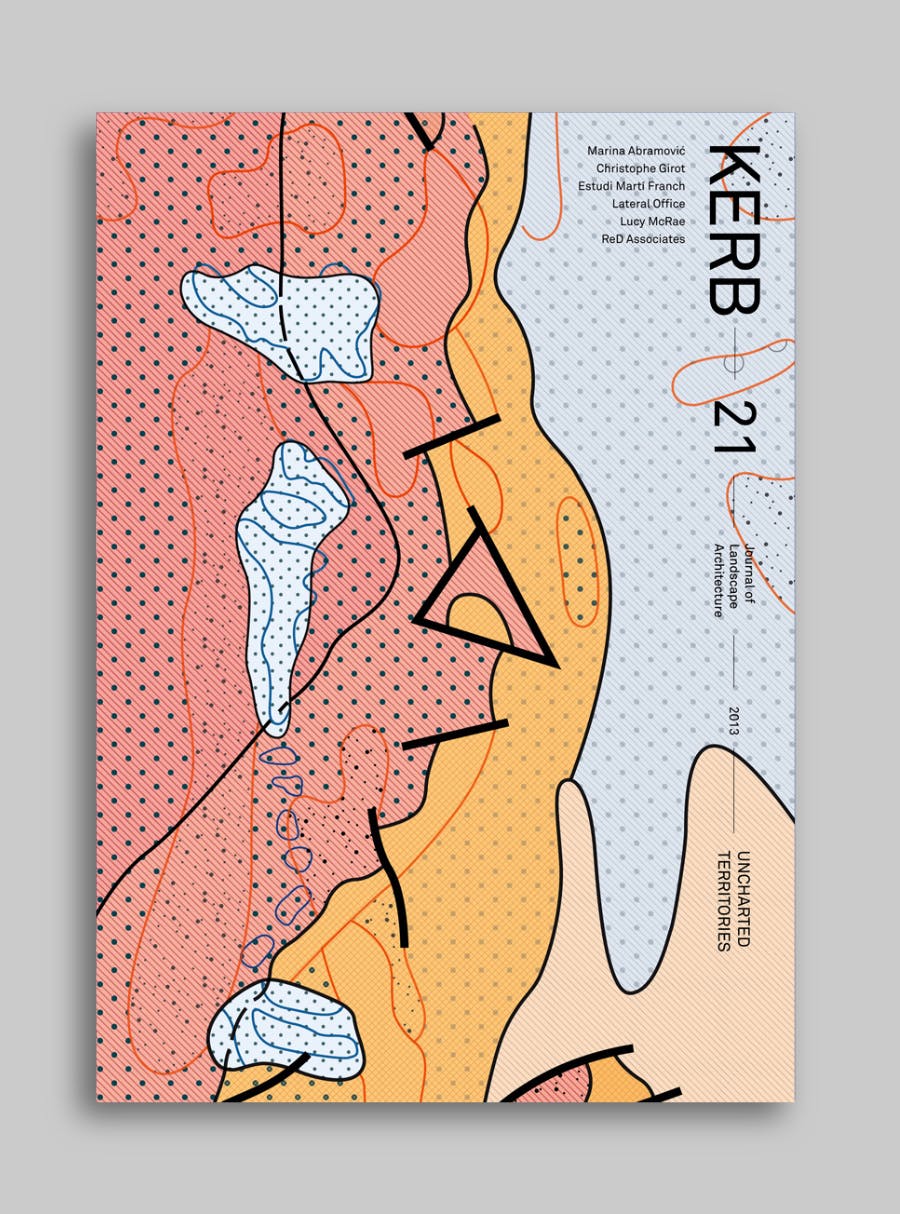

The people who have the capacity to chart these territories participate in a relational field that is negotiated throughout these pages and is at the core of future practice of landscape architecture. At one point in the field exists practice that is constantly in search of the essence of discipline; which translates to a yearning to return to the foundation of landscape architecture. This practice places landscape architecture at the fore of our cities, and landscape architects as the primary place-makers of the urban environment.2 At the other end, there is a practice that operates through a proliferation of disciplinary knowledge, where ownership of ideas and professional identity are fluid. This practice thrives on the freedom of operating at the periphery, drawing resources from the multiple disciplines it skips across. The articles in our journal begin to chart the territories between these two opposing positions. The arrangement of practices relative to these positions is illustrated in our Contents Diagram.

Beyond charting the territory of this field, the fundamental commonality that they share is an adaptive mode of practice. This is representative of an aptitude for wrestling with unforeseeable conditions. These operators can be loosely clustered into three types: intentional, intuitive and instigative. The act of critique serves as an added dimension to these three types and is embedded in and among all practice. Through our own process and journey, we have come to understand the operation of practice as inherently multimodal. Given all practice is continually changing, the value in this clustering is to identify momentary similarities in the works. It is necessarily reductive to understand each project of this diverse catalogue by a single adaptive mode of practice. We understand each submission through the breadth of insight the author allows us and can begin to cluster them accordingly. This allows for patterns to emerge and helps us make sense of this complexity.

Let us begin to make sense of it all. In an essay by Martí Franch he details the journey and development of his practice, Estudi Martí Franch (EMF), as it is engrossed in the work it procures. Martí develops this notion of an accumulated knowledge through both research and testing over every phase of a project. His rigorous approach is distinctively intentional, as it is determined by the ‘real’, and EMF participate in a reflective dialogue.

Martí Franch exemplifies intentional practice, a mode that is grounded in an astute awareness of the present condition, serving as a key informant of their work. It is also rooted in a consciousness of discipline, both responding to and stimulating its immediate context and contemporary practice. Decisions are made by a logic that is born of a knowing of one’s own practice, through research and reflection. This interplay results in an internal knowledge-bank, stemming from a lineage of work. Collectively this provides for an adaptive practice capable of charting the unknown.

Conversely, intuitive practice engages in the absolute present and navigates its course instinctively. This absorption in the present negates the need for ongoing reflection on the lineage of practice. It adapts in unexpected and compulsive ways that allow for hyper-flexibility and is catalysed in the face of limitations. Intuitive practice does not require a consistent understanding of disciplines as it often operates across multiple fields, shifting into uncharted domains. This compulsive creation is driven by sensation, unlike intentional practice, which is conscious in its operation.

These are THE PROJECTS we do together offer us a compelling and spirited insight into intuitive practice, as it permeates every aspect of their lives. Their work is inspired by being open to the potential of everyday happenings, and their practice is curious and experimental. They are comfortably disconnected from formal design discourse as they expand into undefined territories.

Instigative practice actively seeks undefined territories in which to operate. It undertakes extensive research to reveal opportunity and negotiate these uncharted territories through a strategic understanding of past and present factors, this in turn shapes its projections into the future. This practice is based on known unknowns, and requires constant reassessment of project parameters and the legitimacy of outcome.

In our conversation with Lateral Office, we discuss what is required to reveal, and operate in, ‘new frontiers’. They see opportunity in the untapped potential of these remote environments. Lateral Office recognise the limitations of their practice, and while they are excited that the ‘rules of engagement’ are still being written, they are conscious that their scope of operation must be confined to scenarios that have ‘spatial implications’. In an entirely uncharted territory, this guiding principle ensures that they work within their skill set.

We can now begin to compare, contrast and engage with new territories. These adaptive modes chart uncertain territories of two types: realms beyond the scope of discipline, and unpredictable futures. In order to author a disciplinary discourse, we curate an exposition on these adaptive modes of practice. By creating a set of parameters for the formation of other texts, a common ground is established from which discourse emerges.3 From this negotiated platform, we are able to draw projections on the future practice of landscape architecture; thus, our mode of operation is critique. Critique is underpinned by a critical positioning; however, it moves beyond simply making a stance to suggest a further line of questioning toward uncharted territory. When critique is communicated and new lines of questioning offered, ideas are claimed and disciplines are shifted.

Our Contents Diagram starts to spatialise these ideas. Each practice is founded upon a distinct set of values that form the critical positioning of their submission (cross-hair). Their contribution to their discipline is indicative of the critique they offer (darkness of stipple), and their trajectory is determined by their line of questioning (shape). At this point we acknowledge the nature of discourse and must expand the concept of the field. Beyond the two aforementioned positions in the field, between which the extents of discipline can be determined, we understand that this specific discourse is one among multiple discourses and fields. We invite you to be tapped into this critical stream by interrupting this arrangement and unpacking our logic.

Elizabeth Anne Williams asserts that ‘the scope of landscape architecture can no longer exist within our often linear, established ways of working’. We, too, contend that our discipline risks obsolescence;4 we risk our adaptive capacity if we do not depart from the models of our past. Default solutions will not be adequate to maintain operational relevance in times of increasing unpredictability and we must shift towards answers outside our current scope. Navigating this territory craves direction. In tandem, adaptive modes and critique equip us with a direction and capacity to maintain disciplinary authority and conviction in times of uncertainty.

This interplay between mode and critique frames a charting of new territory that continually reframes itself.

Footnotes

-

http://www.maphist.nl/extra/herebedragons.html ↩

-

Girot, Christophe, ‘Immanent Landscape’, Landscape Architecture’s Core, HDM No. 36, p14, 2013 ↩

-

M. Foucault, ‘What is an Author’, Text of a lecture presented by Foucault, Societe Francais de Philosphie, 22 February 1969. Translation by Harari, J. ↩

-

R. Hyde, ‘Future Practice, Conversation from the Edge of Architecture’, foreword by Hill, D, p7, 2012, Routledge Taylor and Francis Group, New York and London. ↩