Territorial and spatial conditioners, the systems concerned with the organisation and order of space, operate at a range of scales. On the small scale, the cohesion of space is driven by a compositional and aesthetic framework, tended to through time. On the territorial scale, spatial arrangement is impacted by environmental, political, jurisdictional, economic and cultural processes. This macro set of operations completely abandons micro scale interactive methods of spatial conditioning. It downgrades the potential to actively shape the landscape, degrading it to simply a passive material on which the larger operations play out. Globalised and economically focused agendas of the territorial are often undertaken with little consideration to local and culturally rich landscapes. Yet the overwhelming nature imposed by the vastness of the territorial makes matters of the compositional seem redundant by comparison (Tension). Documentation and commentary surface such tensions and drive a need for action (Observation). Landscape holds the potential to mediate across the two scales through active and inclusive spatial conditioning employing methods of composition which are sensitive to but not ruled by the operations of territory (Mediation). In doing so, landscape balances the growing complexity of the global1 (where borders are open for certain international flows- namely powerful international corporations - and closed for others - migrants and refugees) with the detail and locality of the micro scale. Landscape re-establishes connectivity between the micro and the macro across time, not to privilege one scale over another in conditioning space, but rather to act as the moderator between territory and terrain (Expansion).

Tension

Matters of territory manifest in the material landscape or terrain, often as border crossings or walls, to secure territorial limits between neighbouring states. Further projections of power and ownership are enforced through maps. The point of transition, thought to have a nominally zero width, through adjoining territories is reinforced, and in a way personified, by these techniques.

This exaggeration of the transition point, as marked by the boundary or line, is limiting in terms of understanding and accuracy.2

This ongoing process, in which the edge of the field is progressively redefined, is undeniably conditioned by the force of time. To try to preserve the edge or outer limit is an omission of this integral and inescapable force. Instead of imposing inhibitive limitations, there is a potential to engage creatively with expressions of territorial identity and the acceptance of the progression of time. We argue that a static and blanket response to the large scale is counterproductive to the complexity inherent in relationships between territories.

For Le Roy, minimal to no intervention is necessary for a superior system of complex organisation.3

We propose a middle ground in which the continuum of time is an essential consideration, and chaos and inhibitive regulation is moderated.

Ambitions to rigidly define territory become more problematic when social and cultural groups are ignored due to institutional opposition to legality or legitimacy. Often excluded from official city maps, informal settlements that commonly emerge on a city’s periphery become invisible to mechanisms of urban regulation. In the case of the city of Lima, a redefinition of a divided territory is called for. Researcher Claudia Bode suggests ‘that by working to include these newly defined territories into the overall ‘image’ of the city, it would knit Lima to itself to form a more coherent whole.’ Mapping here could transition from the problematic to the antidotal, and begin to cultivate a system of fairness across a territorial distribution.

Observation

Similarly within observation lies the power of recording and representing. The changing and shifting of territory, and the need to understand this, initiates visual representations. There exists a constant conversation between the landscape, how we interpret it and the platform on which it is represented. It is this back and forth process of translation that sees the abstraction of information. Combined with the knowledge of other sources, landscape as mediator has the potential to deeply unpack territory.

The borrowing of information sees elements of overlay, collation, and intersection arise to form a visual documentation. Importantly, diagrams and mappings record the larger activity of processes. The inclusion of narrative in this recording captures the more ephemeral and atmospheric qualities at the scale of the individual. The challenge lies in how well a visual language can broaden our understanding of concerns across scales. ‘A Cartographic and Political Enquiry on Borders and Climate Change’ by Italain Limes, works with the complexity of landscape observation through dealing with its dynamic features through interactive modes of representation. Documenting fluctuating borders, rapidly changing ecologies, and even the migrations of people, challenges the static nature of common cartographic methods.

In the first steps of moderating previously disparate conditions of site, landscape drawings can work to communicate to other parties. However, they are still only a commentary and, in some cases as discussed by David Heymann, drawings are superficial in privileging aesthetic excellence for the purpose of industry. Drawing itself is, arguably, relatively passive. There comes a point where a physical realisation, an active intervention, becomes a true mediation between territory and land.

Mediation

Where initial recordings become the foundations for designed interventions, landscape embraces its unique position in the hierarchy of spatial conditioners. Landscape holds the potential to pose equity across the scales of the territorial with that of the terrain. Just as territorial processes can be revealed through a manifestation in the land, so too are acts of landscape mediation.

Mediation involves the consideration of larger networks, broader relations, and processes of global connectivity. It addresses the inevitable changing and fast paced nature of what can be seen as a living, breathing, uncontrollable presence of territory. This must come without neglecting landscape’s inherent ability to work with form and composition through aesthetic and tending frameworks, keeping a rich understanding of the embedded qualities of culture and heritage. The act of considering these polarising concerns leads, in turn, to actions that address tensions between local and global scales of operation.

Landscape is embedded in the layer where the dynamics of territorialisation become spatialised. It can be seen as active in the negotiation between scales of occupation, arbitrating between the larger scale of global networks of economics and industrialisation, and the local scale of the community. As Brent Ryan’s work suggests, through changes of occupation new territories emerge or existing territories are reconfigured. Through this reconfiguration, the landscape in which the territories operate is changed, and hence the processes operating within the territory are changed also. Re-imagining previously impacted sites can ignite new occupation and brands of public life.

Expansion

Conditioning engenders a distinction between an active landscape and the processes impacting upon it. Both play a role in the formation of space, with processes embedded in the land through time, intertwining with the territorial to constantly reshape space. It is in this feedback loop between terrain and territory that landscape is found, and mediation occurs across all scales. From the micro moments to the large scale networks, all are constantly made and remade by interacting conditioning processes. It is from this understanding that we push for a view of landscape not as a static outcome, merely to be mapped and built upon, but landscape as an active player in territorial conditioning.

As Brenner, Schmid and Topalovic explore in Cartographies of Planetary Urbanisation, urban regions can be understood as differential nodes of global and regional networks. This orientation sees space as conditioned by networks which link built systems to territorial systems. They are broadening the scope. Territory is more than what is merely observed on the ground.

At its extreme, this conditioning is talked about in conversation with socioeconomic theorist Saskia Sassen. Sassen critiques the new era of systemic logics emerging from the political economy of the 20th Century. She concentrates on destructive forces relating to globalisation and the enlargement of territorial processes which cut across historical, geographical and conceptual boundaries.

‘Spatial consequences are treated as accidental by-products of these networks’4; yet seeing space as an ‘accident’ of a greater network of processes limits ones ability to grasp and work with them.

The expanded network of territorial conditioners becomes a problem when it is viewed in isolation and removed from the landscape which it conditions. Landscape is not the by-product of territory – it takes an active role in its shaping.

Conclusion

Landscape is in a constant state of change, characterised in correlation to space, place and time. Through a break from traditional cartographic methods of interpreting landscape as static form, to a more dynamic mode of recording process across landscape and territorial concerns, landscape is able to be observed as an active agent in the formation of space.

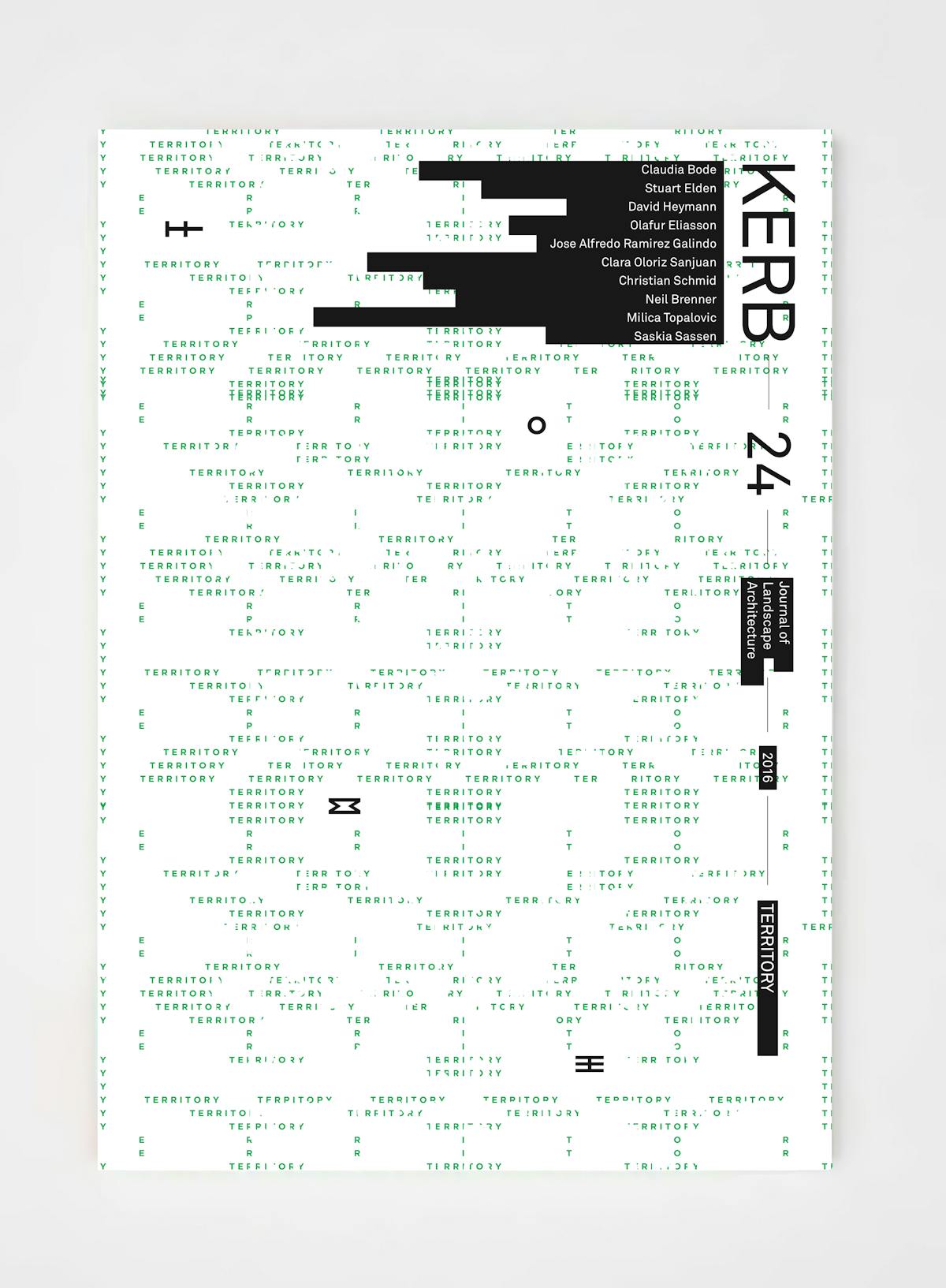

The work presented within this edition of Kerb extends our understanding of territory and landscape, from the vast network of processes to the moments experienced in place. By acknowledging and engaging with landscape as a spatial organiser, it then becomes a mediator of processes across all scales of operation.

GLOSSARY OF TERMS

- Land: material, ground plane, canvas, micro scale.

- Landscape: an abstracted view of terrain within a perceivable range, the mediator between scales.

- Field: an invisible barrier or force.

- Volume: the contents of the field, the macro scale, the network of territorial registers, processes, and relations existing through time.

- Edge: the perceivable range of the volume.

- Boundary: the mark of an area’s limits.

- Border: the administrative division or demarcation of ownership, or, to be adjacent to.

- Barrier: an obstacle preventing movement .

Conditioning: to have a significant influence on, or to bring (something) into the desired state for use, or to set prior requirements on (something) before it can occur.

Footnotes

-

This complexity is apparent in that changes to any one system operating within this territorial scale has ramifications for other systems within the vast global network. See: A Conversation with Saskia Sassen and Schmid, Brenner and Topalovic’s Cartographies of Planetary Urbanisation, published in Kerb24. ↩

-

A Conversation with Stuart Elden: Approaching Territory. Kerb24 ↩

-

Roy, Louis G. le, Vollaard, Piet., Boukema, Esther, & VeÌlez McIntyre, Philippe. (2002). Louis G. Le Roy: Natuur, cultuur, fusie = nature, culture, fusion. Rotterdam: NAi Uitgevers. ↩

-

Easterling, K. (2014). Extrastatecraft: The power of infrastructure space. ↩