In all landscapes, there are elements of tension that challenge and contest our experience. As students of landscape architecture, our awareness is heightened as we are encouraged to provoke and test. We are perplexed by tensions that exist within landscapes. The English Oxford Living Dictionary defines tension as ‘1. A strained state or condition resulting from forces acting in opposition to each other,’ and ‘2. A relationship between ideas or qualities with conflicting demands or implications.’

We began observing such conditions arising from the competing demands that are placed upon landscapes. The conference Contested Landscapes/ Lost Ecologies, convened by Arctic Frontiers in 2013 at the University of Tromsø, questioned the conflict that is created by extraction processes in the Arctic Circle. The conference argued that ‘it [is] necessary to develop a continuous and critical discourse defining, describing and challenging the dynamics and friction between the logics of exploitations and the landscape as a well-balanced ecology.’1

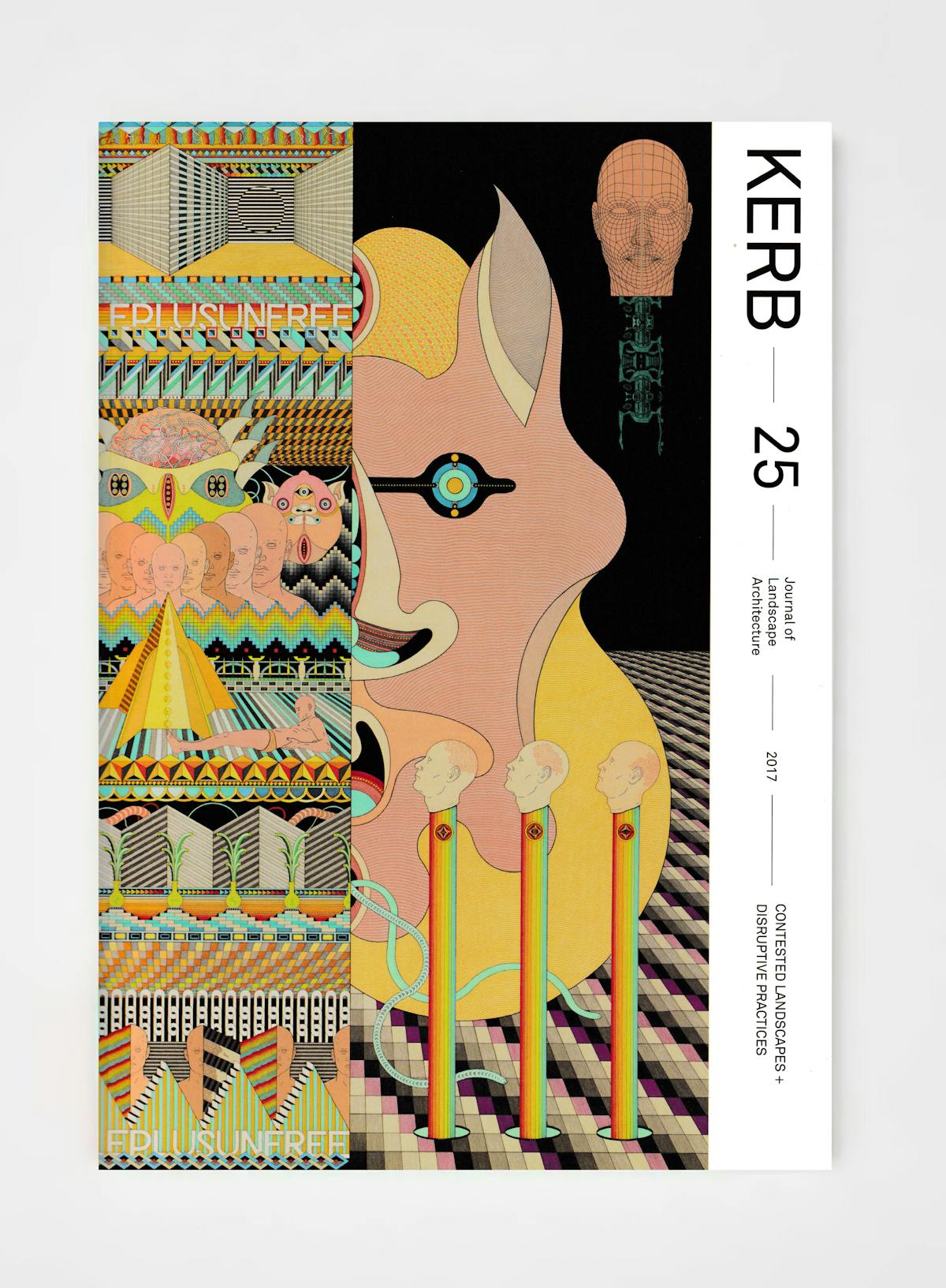

We used the conference as a basis for discussion, which provided a framework for this year’s theme. To begin, we reiterate a question inspired by the conference: ‘are social, political and economical needs compatible with agents and practices that harbour a holistic view on landscape?’2 In Kerb 25 we wanted to examine the value systems at work in landscapes and the conditions that arise from them. We enquire: are contested landscapes a result of disruptive practices or are disruptive practices a result of contested landscapes?

Michael Murphy explores landscape through the lens of control, understanding that ‘the Landscape is formed by processes, such as geology or climate or economics, over which designers exercise little control and, as a consequence, which limit designers’ influence over many aspects of the landscape as others might perceive it.’3 From this, two questions arise. First, how do these processes or competing influences alter and affect landscapes? And second, as a result, how much control do designers really have?

We are presented daily with global events such as war, mass migration and environmental degradation. We found that, no matter their geographical location, everyone is affected by global events in some way. We also found that all landscapes are multi-faceted, comprising of complex living systems. All landscapes experience some form of tension. In presenting our theme Contested Landscapes + Disruptive Practices in Kerb 25 we intend to examine global conflict from a local standpoint.

As Murphy explains, all landscapes are formed and controlled by processes, whether they be social, political, economical, environmental, ecological, geological. Given that we all have observed a degree of contestation in our environments, we looked to the future and wondered how this might affect the practice of landscape architecture within Australia and abroad. With expected population growth, rising energy demands and the inevitable warming of the planet, we wondered how future landscapes would react.

The political climate of 2016 and 2017 was a major talking point. It inspired further questioning of contested landscapes and disruptive practices to grasp how politics, development and culture affect and shape landscapes. From the destruction of Syria and the refugee crisis, the controversy over the North Dakota Pipeline, the resurgence of right wing populism and the introduction of Brexit, and the US election and debate surrounding the US-Mexico border wall, these events all contributed to the framing of Kerb 25.

In exploring the drivers of contestation within landscapes, disruptive practices and conditions, we selected articles for this issue that reflected either a contested landscape, a disruptive practice, or a combination of both. An article that interrogates a contested landscape is ‘Geographies of Violence: Island Prisons, Prison Islands, Black Sites’ by Suvendrini Perera and Joseph Pugliese. The authors examine intervention in the Middle East and its relationship to the current refugee crisis. Rottnest Island and the imprisonment of First Nation Australians is considered against Manus Island and Nauru, thus questioning the Australian Government’s treatment of Indigenous Australians and refugees. Perera and Pugliese frame ‘black sites’ as island prisons used historically to isolate individuals from society. They observe that the spatial advantages of an island prison lie in its state of control and separation from the mainland, thus creating a contested landscape.

We conceived disruptive practises through two lenses. First, we referred to those practices that created physical disruption, for example extraction processes. Kees Lokman’s article ‘Wicked Problems Along Canada’s Carbon Corridor’ explores a physically disruptive practise that contributes to social, environmental and spatial conflict. He examines the resource rich area within British Columbia and Alberta that supports major gas, oil, coal and hydroelectric projects. The level of exploitation within this area is increasing due to demands on energy. Despite this, the area IS experiencing vast ecological and spatial transformations, along with demographic conflict and disruption among farming and First Nation communities. Activities such as the practice of resource extraction lead us to question the role of the designer in the future: what new landscapes will we be working with, and how will such landscapes affect the future of design?

Second, we also understand disruptive practices to include those practices that disrupt normative conceptual frameworks or, as Leyla Acaroglu suggests, practices that are ‘functionally imbued with the objective of challenging the status quo and making positive change.’4 RMIT student, Asa Kremmer, who studied at Delft University of Technology, observes in his article the relationship between colonial maps ‘as a tool to demarcate walls, fences, checkpoints, and divide people, places and identity.’ In ‘Atlas of Borders’, he outlines how the colonial redrawing of maps saw the displacement of people and entire communities. His article positions a disruptive practice that reduces experiences, culture and connection and proposes a new form of mapping at multiple scales that depicts multidimensional spatial conditions. These themes are evident in other articles in Kerb that similarly highlight how populations are subject to environmental disasters, land loss, climate change and rising sea levels.

Alexandra Mei’s project titled ‘Rise: A Guide to Boundary Resistance’ comprises both a contested landscape and a disruptive practice. Her project examines a watermark on the coastline that is used as a bureaucratic mechanism for state ownership. For the Biloxi-ChitimachaChoctaw tribe on the Isle de Jean Charles, Louisiana, this line divides native land and state owned water. As water rises over the next 50 years the tribe and many other coastal communities will lose their land. Furthermore, their land has been subdivided by a nearby oil industry and they will have to leave. Mei’s project provides tools and methods to reclaim land that holds culture and identity even after they leave. If the mark can be altered and obscured the tribe will remain in ownership of their land. This project explores the act of boundary making and resistance.

Since Kerb’s inception in 1997 it is undeniable that globalisation has allowed for greater numbers of students to access education abroad, and for students to engage with national and international concerns throughout their education. Discussions, articles and projects within this edition of Kerb push the question of ‘what is now, what can be and what will be’ in the practice and theory of landscape architecture. As students, we are encouraged to be curious, to engage with and examine landscapes, and the complexities that form them. Through Kerb 25 we have recognised that events of 2016/2017 and beyond may affect the practice of landscape architecture in the future. Kerb 25 asks questions and pushes into the unknown. In presenting Contested Landscapes + Disruptive Practices we aim to explore whether the competing demands of the twenty-first century are compatible agents that can foster holistic landscapes. Kerb 25 invites its readers to question whether contested landscapes are a result of disruptive practices, or are disruptive practices a result of contested landscapes?

Footnotes

-

Contested Landscapes - Lost Ecologies / proceedings of the Arctic Frontiers conference, 2013, University of Tromso, Norway, pp. 1-3 https://www.arkitektur.no/contestedlandscapes-lost-ecologies ↩

-

Ibid ↩

-

Murphy, M 2016, Landscape Architectural Theory: An Ecological Approach, Island Press, Washington, USA ↩

-

Acaroglu, L 2014, ‘Making Change: Explorations into enacting a disruptive pro-sustainability design practice’, RMIT University, Melbourne, Australia ↩