This paper explores strategies for teaching landscape architecture design studio that enable unstructured and often unpredictable events to inform, and be incorporated into, the design process of complex urban sites.

Complex urban design briefs in studio often explore notions of ambiguity and multiplicity, as a way of engaging the pressures and opportunities which affect the urban landscape. The possibility that the brief may change swiftly and comprehensively during the project is less often addressed. Based on two urban case studies, this paper discusses strategies and examples of ways to embed this characteristic directly into landscape architecture studio teaching.

The two case studies are urban sites currently under development in New Zealand, where the designers’ brief is being substantially altered during the design process due to a range of political and economic events. This has resulted in rapid and unpredictable change in the brief and programme, and the future urban landscape architecture for these sites.

New Zealand’s capital city of Wellington is sited on large natural harbour. The waterfront is the interface between a small but intense urban centre, and a spectacular and often windblown harbour. Access and control of the waterfront has, as in many such situations around the world has shifted in recent years from domination by trade and transport considerations to a focus on creating public urban space.

The Wellington City Council developed a comprehensive plan for the waterfront which included parks, plazas, boulevards and new buildings. The city’s council-backed masterplan has been strongly challenged by well-organised public protest, mainly around the perception that the council’s plan will create a barrier or wall between the city and harbour. Such protest action could conceivably halt the work and completely redirect the design process. Thus the designers could be required to renegotiate and perhaps reverse many of the programmatic, formal and spatial decisions already taken.

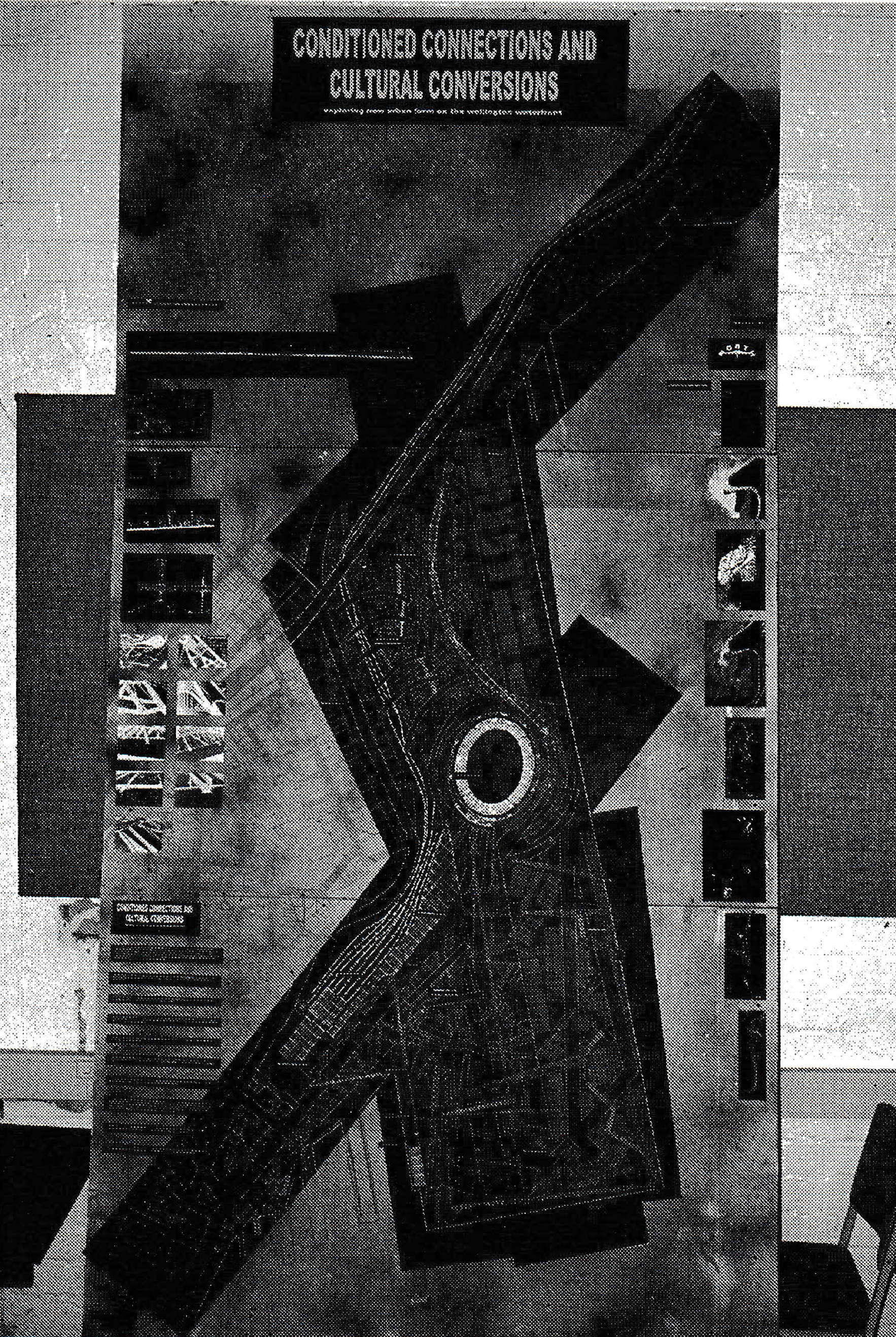

Conditioned Connections: Peter Matthews, Paul Murphy, Michael Casssidy

The second case study site, Auckland’s Viaduct Basin, has been dramatically altered since 1995 to accommodate the 2000 America’s Cup, a premier world yachting event. The future use and urban form of this significant area of the city ultimately hinged not on urban design theory but on the vagaries of the wind and the highly technical business of elite yacht racing.

These two case studies can be mined for a number of strategies which can structure a landscape architecture design studio:

- ‘Game’ strategies enforcing rapid reversals and diversions on the studio process can be generated randomly (by dice, for example);

- Role-Playing (other than as designer) for their own and others’ projects -resulting in the selective (or even malicious) reinterpretation by peers;

- The catalytic addition of completely new influences into the project by the instructor, such as additional infrastructure, or catastrophic demolition;

- Adaptation of modeling techniques to allow rapid and massive redeployment of design components.

The strategic approach to the design process becomes more useful than an adherence to certain conventional landscape architectural tenets. A thorough and systematic survey and analysis of an existing site and brief may be rendered partly or wholly redundant by the kinds of changes that occurred in the waterfronts of Wellington and Auckland. A formal or typological approach may also be left stranded if bits of the fabric are drastically altered. Exploring a strategic process is one way of absorbing and moving forward with an array of shifting parameters.

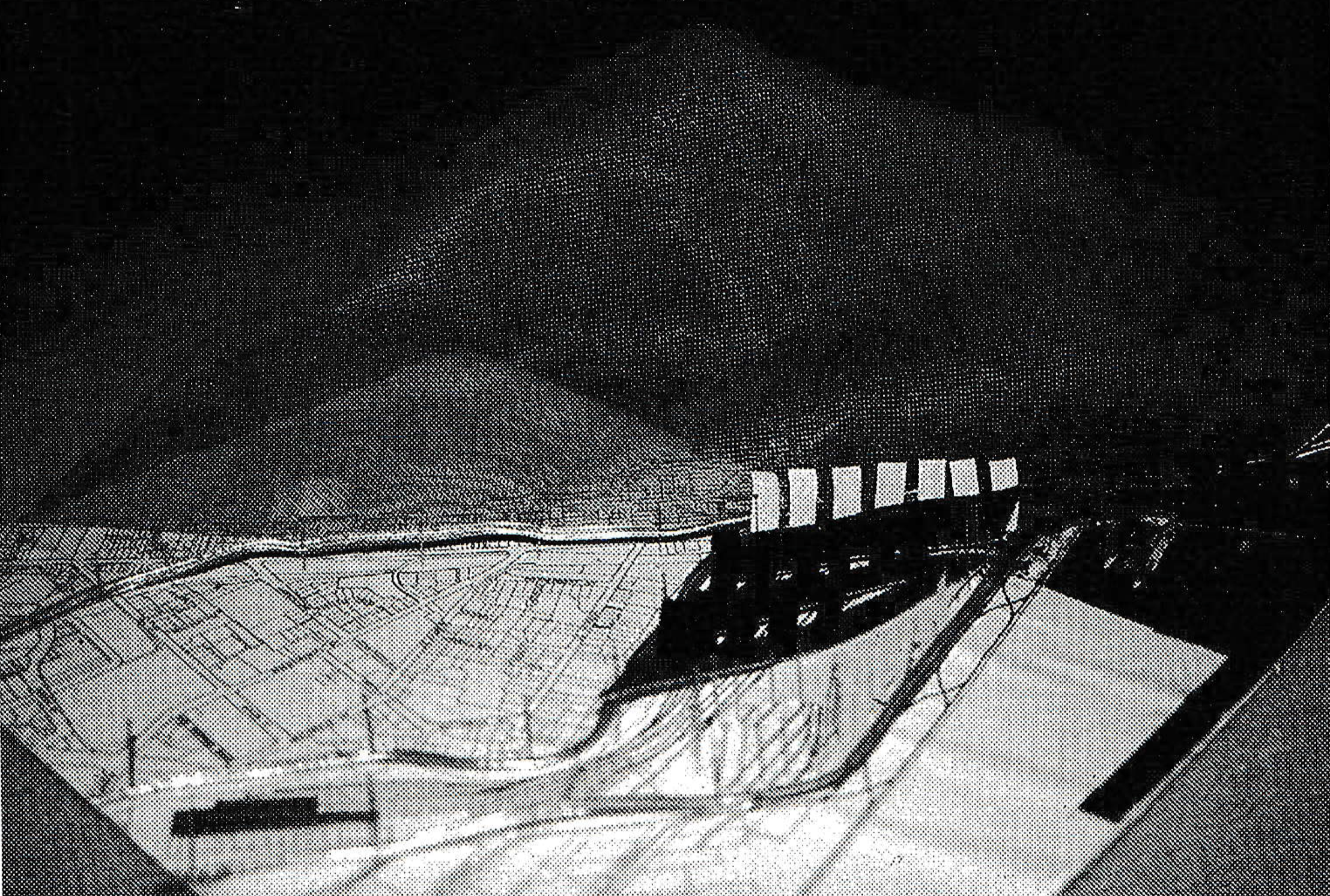

Viewing and Being - working model of the site: Helen Mellsop and Nicky Treadwell

Viewing and Being-perspective; showing towers and screens: Helen Mellsop and Nicky Treadwell

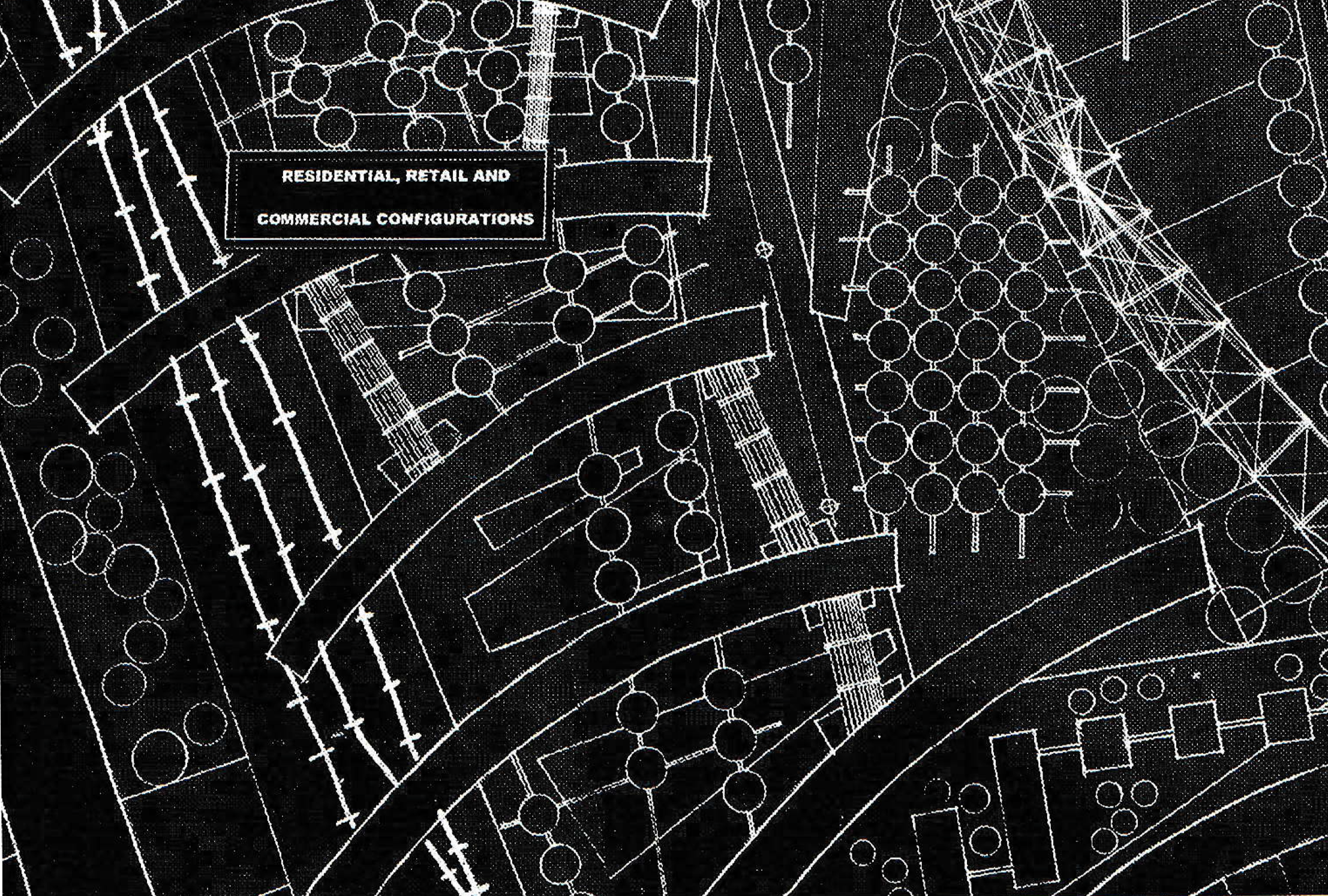

Conditioned Connections-detail of residential area of site plan: Peter Matthews, Paul Murphy, Michael Casssidy

Fourth year students at UNITE used different strategies for the project sited on a large disused piece of railway land close to the Wellington Waterfront project already mentioned. The brief in this instance was devised by the Architectural Centre in Wellington and was offered to a range of design teams who all worked on a series of fixed elements and an assortment of physical and programmatic variables. These students ended up with the ‘wildcard scenario’, which called all elements into question.

The first project by Michael Cassidy, Paul Murphy and Peter Matthews used one fixed element - the newly constructed stadium on the site - as a centrifuge around which to whirl other elements and aspects of the site. Sketch models were used to explore this process without programmatic fixity.

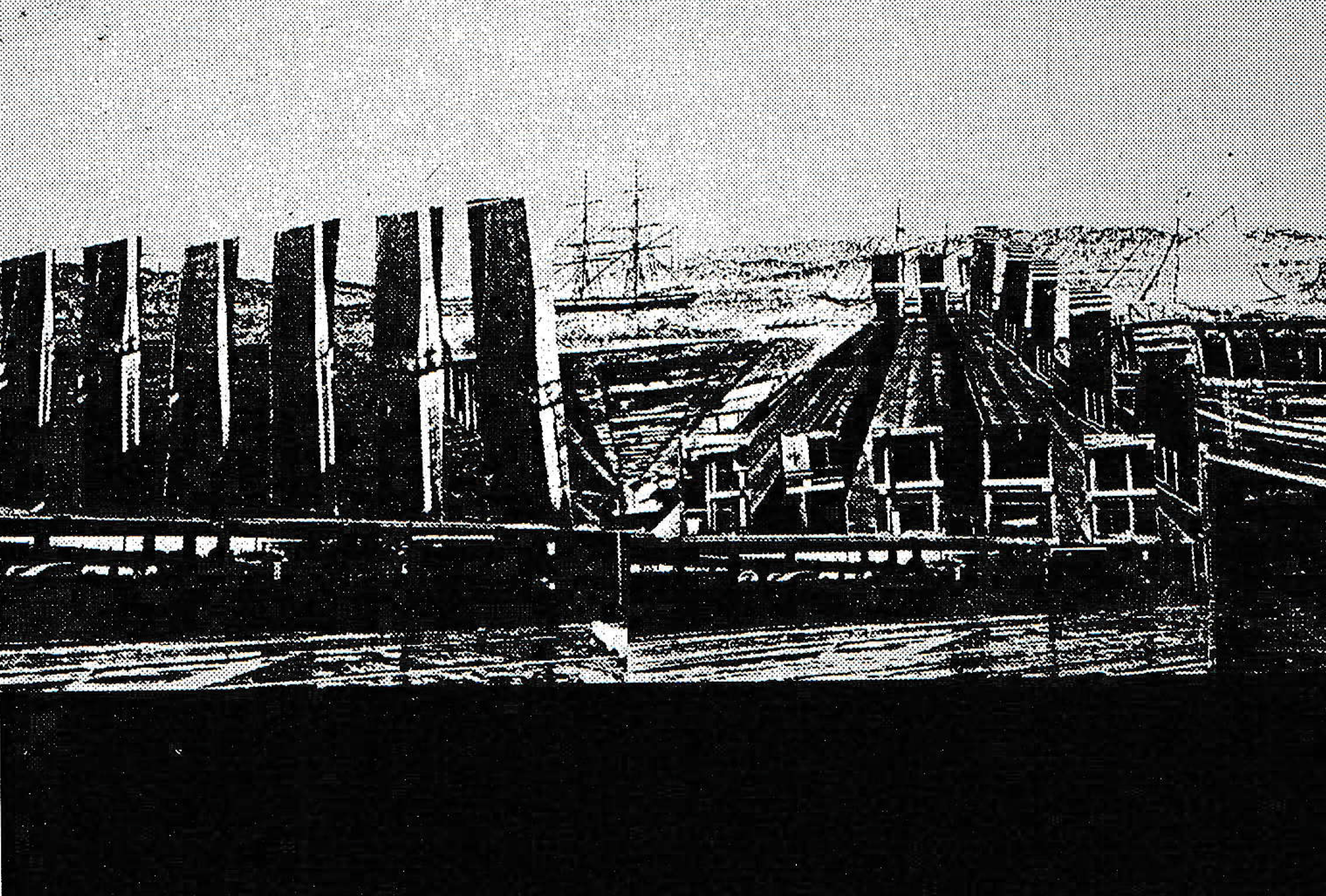

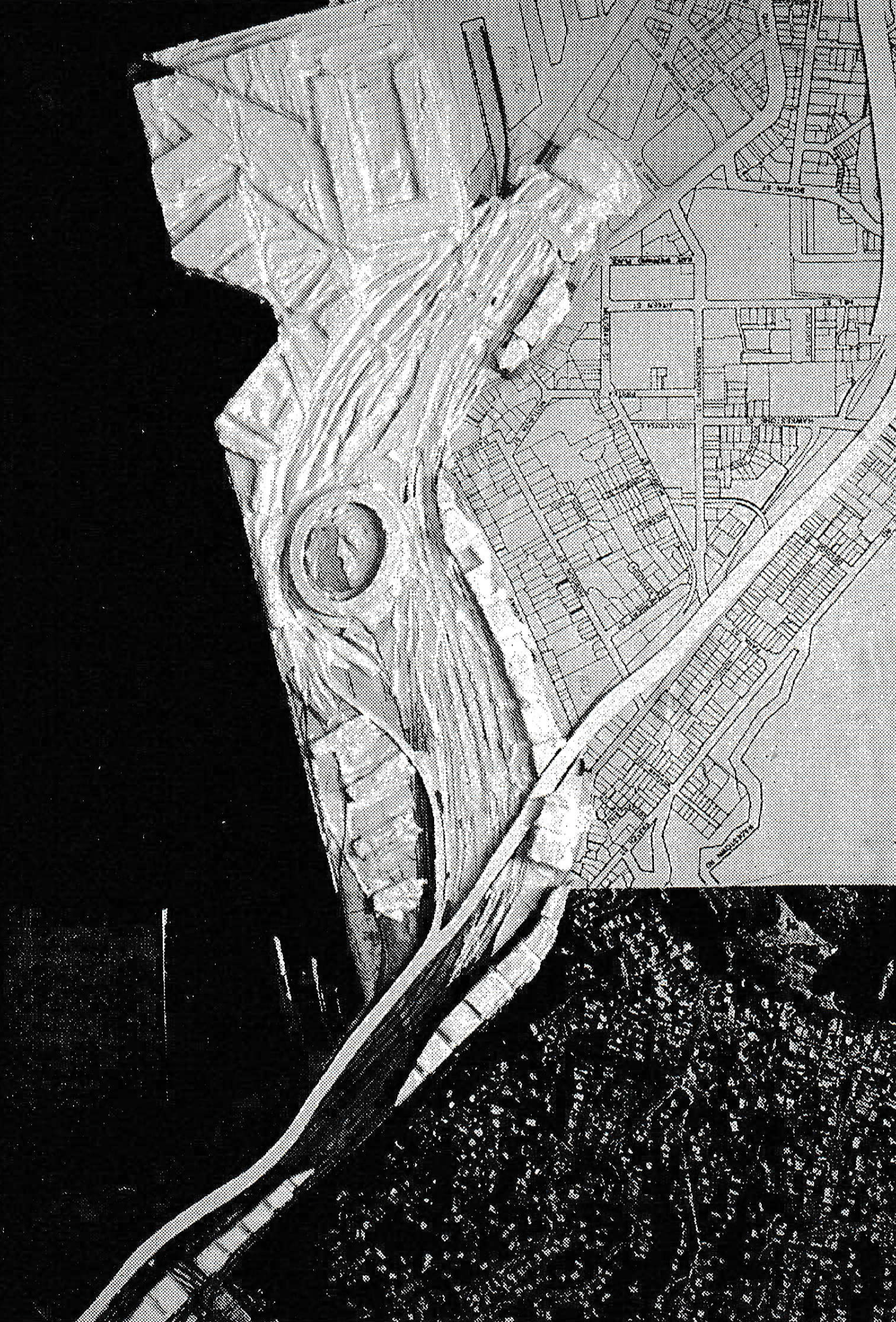

The second strategic approach, by Janice Penney and Amy Trubovich took its cue from the inherent changeability of the site. They identified and mapped the incremental changes and alterations that had happened, such as significant tectonic uplift in the 1855 earthquake, repeated episodes of land reclaimation, and treated their own project as an ongoing process of sedimentation and re- exposure. New elements or unexpected changes to the surroundings were absorbed into this relentless process, which they initially explored with a modelling process that layered, sedimented then scratched away.

The third scheme, entitled ‘Viewing and Being’ by Nicky Treadwell and Helen Mellsop was based on an analysis of urban space and experience of movement in such space by Lefevbre. Their initial modeling process explored the relationship between the body moving in space and the view, linking the intimate scale of movement to the vast scale of the city and harbour through the juxtaposition of platforms and viewshafts which directed the gaze both horizontally and vertically.

These three all chose to keep the stadium, but could also have adapted their strategic design process to accommodate its removal or relocation. The wildcard scenario, with its lifting of restrictions stimulated design responses which actively engaged with the inherent changeability in the urban landscape. Change becomes a catalyst for design, rather than a frustration of it.

The splintered fossil- working model of site: Janice Penney and Amy Trubovich

Design studios based on this premise allow students to actually experience the process of sudden change in a complex brief, giving them an appreciation of the significant design potential inherent in this aspect of the urban realm, and enabling them to develop the ability to respond effectively to the real situations they will encounter in the contemporary urban landscape.