Over the last decade, rapid urban development, fuelled by the imperatives of growing economies, has redefined the role of the landscape architect in South East Asia. In cities such as Kuala Lumpur and Bangkok, public awareness and demand for design professionals has resulted in a high rate of recruitment from countries such as Australia, England and the United States. Local universities struggle to meet the demands of the private and state sectors and Australian firms are becoming increasingly aware of work opportunities in countries such as Malaysia. While projections of further sustained economic growth remain optimistic, Australian professional involvement in the region can only increase.

However, Australian involvement in the landscape architecture ‘scene’ in Southeast Asia invites certain crucial questions about design practice as a process situated within a specific regional context. For example, is it possible to have a universal design culture, where ‘design skills’ are ‘transportable’ and trained designers able to design anywhere on the globe? Or is design always contextualised by regional specificities? What sort of complexities emerge in practice, when working in different countries where cultural assumptions and socio-political histories are different?

Examining the practice of landscape architecture in a country like Malaysia can therefore help to destabilise assumptions about how a designer operates and howdesign vocabulary can be influenced. Too often, the business of designing is seen to be mundane and not quite as interesting as discussion of the design itself. In this way, ‘a design’ is then divorced from its context. But the reality remains that ‘designers’ operate within market economies, where development is linked to the flow of capital, controlled by various stakeholders.

Specific regional conditions can therefore require designers from Australia, based in Malaysia, to operate in different ways, in order to attract and maintain business. This article seeks to examine these crucial differences. How do design companies seek work? How do regional conditions affect a design process? This analysis moves the focus away from material project critique to examine the wider socio-cultural pressures affecting the business of landscape architecture. In order to do so, some familiarity with Malaysian economic and political history is necessary.

One of the largest flagpoles in the world overlooking Merdeka Square in central Kuala Lumpur

The Malaysian State

The Malaysian State has always been controlled by an uneasy alliance between the elites of the Malay and non-Malay (mainly Chinese) communities.1 In such a pluralist society, identity politics have always played a vital part in economic and governmental policy, affecting the role of a designer operating in such a volatile environment. Power, fractured amongst different racial communities, was a legacy of British colonial rule. While encouraging Chinese and Indian immigration to provide labourers to exploit raw materials to fuel the Industrial Revolution, the British were also instrumental in fostering a Malay bureaucratic class, which after independence in 1957, retained control of the bureaucracy, judiciary, military and the police. Meanwhile, in the 1960’s, Chinese immigrants to Malaysia had gained control of the areas of commerce and industry not in the hands of foreign capital. With Malays wielding political power and the Chinese controlling a substantial chunk of the domestic economy, social tensions inevitably arose, culminating in racial riots in 1969. This occurred largely in response to Malay perception that the country’s wealth was in the hands of non-indigenous migrants. One of the significant outcomes of the 1969 riots was the implementation of the New Economic Policy (NEP), a twenty year strategy designed to spearhead Malaysia’s entry into a modern economy. A major objective of the NEP was the redistribution of economic wealth along communal lines in such a manner that by 1990 Malays would be in control of significantly greater domestic capital and resources.

Economic Growth

State involvement in the economy expanded enormously during this period with the subsequent creation of a Malay business class, where the Malay elites in the bureaucracy were joined by the emerging state sector managers and client business people spawned by the NEP (Crouch, 1993). Chinese economic influence declined - although consistent growth in the post-Independence economy ensured that their influence remained substantial. Significantly, rapid economic growth2 and structural change resulted in the expansion of the middle class, particularly among the Malays. After independence, most Malays were of rural origin aside from those in the bureaucratic elite. It was not until the inception of the NEP that Malays were ensured preference in gaining access to tertiary education and government jobs, with private employers being pressured to recruit Malays to white collar positions. Although the growth of the Malay middle class was rapid during 1970-1990, Chinese, and to a lesser extent, Indian communities, were also becoming more affluent. By 1990, third of the entire population had become middle class. Greater wealth led to increased consumer power and the growth of the design professions.

In particular, the Second Malaysia Plan of 1971-75 gave considerable attention to the building industry, designating it as the engine for economic growth. This paved the way for a subsequent construction boom and property development expansion. The ensuing demand for designers was however, still very much under the aegis of the NEP and its associated focus on redistribution of power and wealth.

The Politics of Race & Culture

In Malaysia, ethnicity is inextricably linked to policy, which affects the ways in which business is carried out. Effectively, chasing work becomes a political exercise. This is particularly true where governmental support is required, or capital for development flow from companies controlled by the government. In fact, studies3 have explored the crucial connections between ethnicity and power in Malaysian corporate culture. revealing hegemony, rent seeking and patronage to be vital aspects of corporate life. This affects the nature of urban development and the choice of design firms. In addition, private sector projects can be initiated by seemingly private firms which are in actuality, companies controlled by political parties representing the interests of the three main ethnic communities in Malaysia. Not surprisingly, the largest corporate empire in Malaysia belongs to UNO, the dominant Malay party.

Designers from Australia and New Zealand are accustomed to dealing with a relatively homogenous, dominant Anglo culture and designers choosing to work in Malaysia can be confounded by the complexities inherent in having three or four cultures co-existing in tenuous harmony. Colin Bennett, an architect from New Zealand recalled that,

“It took us a long time to find influential friends; you can waste a lot of time and money talking to the wrong people. And you have to learn the local customs and try to get an understanding of the politics of race here.4”

In practical terms, what Bennett refers to as ‘the politics of race’, describes, particularly in public sector works, how contracts and tenders are awarded. Additionally, it involves identifying informal networks of financiers and developers in order to attract work and having at least one Malay partner in business to satisfy the requirements of Malaysian corporate policy. All these issues have racial dimensions. A Malay partner of a large landscape architecture firm in Kuala Lumpur admitted that contacts were invariably pursued with ethnic related issues forming some basis for ongoing relationships. While his Chinese partner would liaise with Chinese developers and financiers, he would personally ensure relationships with Kuala Lumpur City Hall, dominated mainly by Malay bureaucrats. The success of the firm, while no doubt owing to their expertise, can be seen to be grounded in understanding how to utilise communal politics to their advantage.

Economic activity is also defined differently in the region. Unlike Western economic cultures, where work and family life are separated, economic cultures of Asian cities are based upon two parallel systems5. The first, is a recognisable, modern, firm-based economy, and the other, a more subtle, pre- industrial urban economy comprising complex networks of diverse and usually small operators functioning within extended systems of kinships. Notions of kinship play an important, although often unacknowledged role in economic activity in Malaysia. Malay kinship is supported through actual legislation (eg. NEP) while Chinese interests are fractured along loyalties to clan, (a legacy of mass immigration requiring cultural support), and family (endemic to Chinese culture). A Chinese developer6 in Penang, whose family controlled a property a portfolio worth over A$600 million stated that he had always directed tenders for design work on his properties towards Chinese firms as he “felt more comfortable dealing with his own kind”. Hokkien-speaking landscape architects were of course preferable, narrowing the field further. It would not be inconceivable for this developer to direct work to a foreign firm employing a Hokkien Chinese landscape architect in preference to a local firm of Malay professionals.

Interest Groups and Political Links

In seeking to maintain or strengthen ethnic identity, the political motivations of ethnic interest groups can also influence design decisions. Traditional Chinese clients, for example, may require that feng shui7 is incorporated in site layout, or that recognisable Chinese forms are used.

The Kuching waterfront development for instance, utilises Sino imagery in it’s ‘Ming- inspired’ forms and sculptures (eg. Chinese dragons), which celebrates the rich heritage of Chinese settlement in the town of Kuching. Acknowledgment of the large indigenous population of Kuching can also be found in the Iban motifs used as paving patterns. However, it is important to recognise that the principal developer of the project, namely the State Economic Development Corporation of Sarawak, was largely Chinese controlled at the time. Their preferred civic image had stronger links to Singapore and Hong Kong than to more Malay regions such as Kuala Lumpur or Seremban. As a federation, Malaysia’s different regions are often under the economic control of different ethnic groups. Penang for example, is another region where Chinese capital exerts considerable influence on townscape.

Similarly, public works in the capital city of Kuala Lumpur tend to reflect Islamic or traditional Malay imagery, although the glass and concrete towers of the International style predominate among the large buildings in the city. Tourist centres however, are built in the derivative Malay style, using vernacular kampong8 forms. Paving patterns are based on traditional Islamic geometry, and built elements such as walls or arches tend to be inspired by some aspect of Malay indigenous architecture or culture. Within the capital city, the drive to portray a consistent and inherently Malay civic image, links in to the growth of tourism and the rise of Kuala Lumpur as the definitive urban capital of the region. The town, as the financial centre, has a representative function, and civic works tend to reflect the desired image that politicians wish to encourage in order to attract investment and status. To achieve this, public development authorities, pursuing the policies of the NEP, are often employed.

In 1971 for example, the Urban Development Authority (UDA) set out to restructure Malay interests in urban areas by generating joint ventures between government and private sector property owners. The strategy involved helping Malay developers to acquire properties with potential for development by providing incentives such as a 30% rebate on development charges associated with land acquisition. The Dayabumi project in Kuala Lumpur was acquired by Petronas9 with the help of the UDA. The tender for the project was awarded jointly to Arkitek MAA and BEP Architects, both Malay firms. Part of the design vocabulary associated with the project involved Islamic motifs, a stylistic convention well suited to the political imperatives of the development.

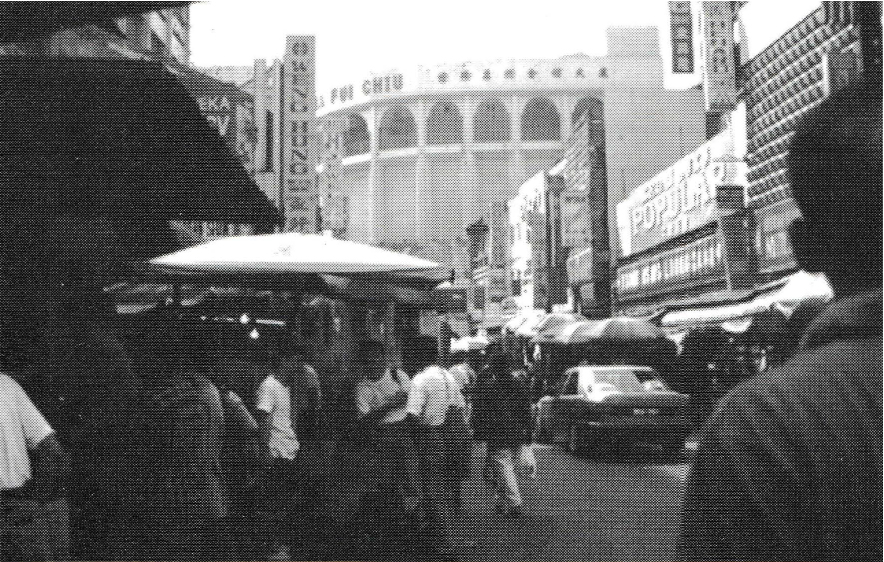

However, despite representing Malay interests, development authorities such as the UDA can be lobbied against by other interest groups, who collectively wield significant influence. For instance, the proposed conversion of Petaling Street into a covered mall has been developed in consultation with Chinese dominated business groups such as the KL Hawkers and Petty Traders Association, Federation of Chinese Assembly Halls, and the Selangor & Federal Territory Chinese Chamber of Commerce. Despite the involvement of the UDA, the Chinese flavour of Petaling Street will no doubt be retained and augmented by pressures from the interest groups represented within the steering committees associated with the project.

In the above examples, macro political forces aligned to the interests of race and culture, operate to influence the design process at every step.

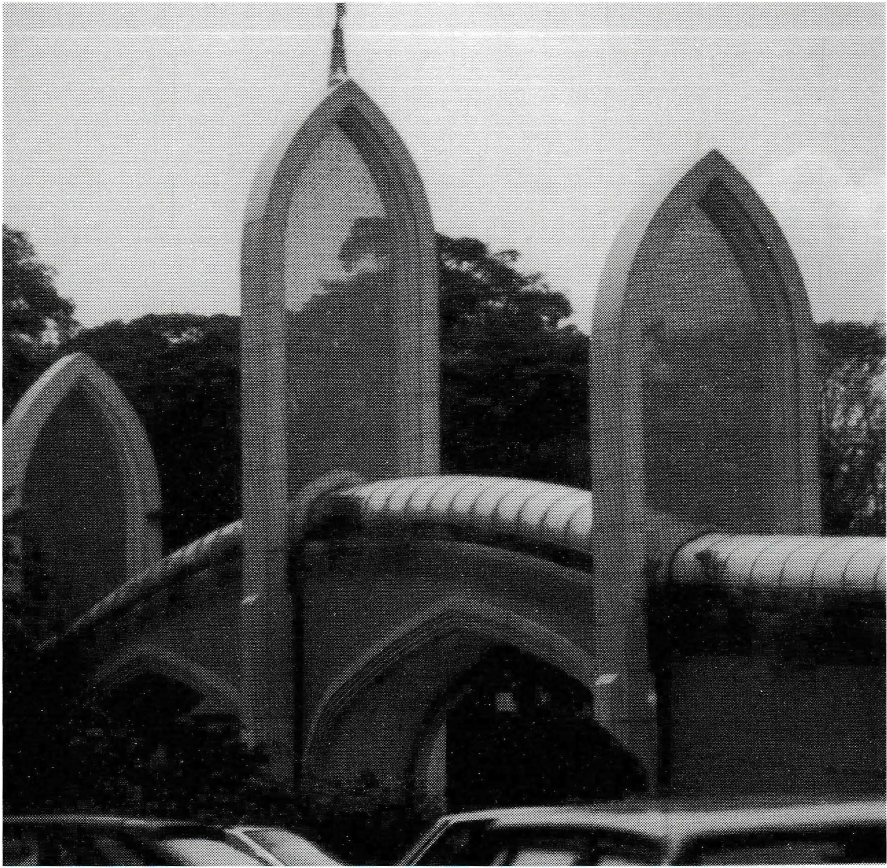

A pedestrian footbridge designed with Islamic arches in central KL

The Search for a Malaysian Identity Significance in Design

The search for a representative Malaysian identity, imaged through the design of the built environment, has been a complex and contradictory process. As a relatively new nation state (since 1957) whose population makeup consists of three quite disparate cultural communities and four or five major religions, Malaysia’s national identity has been in the process of active construction over many years. Following the 1969 riots, the government became aware of the need to promote a Malaysian identity that sought commonality and unity amongst all the different racial communities.

Certain cultural expressions that could not be exclusively claimed by any one racial group, were celebrated as a shared heritage of Malaysian culture. Love of food, for instance - or shared festivals, or indeed, open spaces such as national parks, came to be promoted as a common (i.e Malay, Chinese, Indian) heritage to all.

Meanwhile, as the fields of architecture and landscape architecture became more prominent with the acceleration of urban development, portrayal of a Malaysian identity through the built environment became the dominant discourse pursued through Government channels in conjunction with emerging professional design bodies such as PAM10 and ILAM11 The results have been patchy. Some designers have resorted to plundering iconographies of historical design and transposing them in the form of Malay-style roofs on commercial buildings,12 or buildings in the shape of a Malay kris.13 The consensus among most critics has been that this early experimentation has resulted in pastiche and parody — post modern in its worst sense — where decontextualised elements signify a tenuous link to a constructed past.

Petaling Street Market

Jimmy Lim, the Senior Vice President of PAM expressed his frustration about significance in design in a recent interview,

“you cannot just pluck a thing out of the air and say that this is it! If the government talks about using the Malay house as a symbol, it is not enough, it just leads to more problems.”

According to Malay interest groups, to portray a sense of Malaysia is to construct a visually Malay image. However, Malay culture has never been urban in character, and its heritage of rural craftsmanship and culture sits uneasily with the world of multistorey skyscrapers and global capitalism. Attempts have been made however, to engage landscape design to express cultural identity. For instance, Mini Malaysia, a theme park located near Malacca, developed by Malacca’s State Tourist and Progress Boards, reproduces an ideal Malay village setting using regional architecture and rural landscape features such as indigenous plants and surface treatments. The project seems to succeed as an elegant museum piece but as Malay culture moves towards urbanisation, the park has been described as a showcase for a particular type of Malay identity14 constructed for the consumption of the now-urban Malay middle class who have a less and less familial link to the rural environment. Rather than a true representation of culture, Mini Malaysia mirrors the function of Disneyland’s Main Street, USA — by offering a package tour through an imaginary setting of an ideal society.

With the political necessity of creating and a representing a united Malaysian identity, is no wonder that local firms working in the public arena, prioritise image-building in their design work with attempts to express culture and it’s ongoing expression through the design of the built environment. The designers for Taman Teknologi15 for instance, utilise what they term, an ‘ethno-botanic’ quality in their planting scheme using indigenous plants with the potential for future research and development purposes. While still utilising an indigenous planting framework, the ideas of technology and commercial research (very much a part of Malaysia’s next step towards a fully industrialised economy) are incorporated into the choice of planting material.

Other attempts at expressing culture can be found in proposals for the Klang River redevelopment along Central Market and Jalan Raja Laut. One proposal reinterprets Malay kites as sculpture, using images of Malay boats and fish species found along the river Klang as decorative friezes and incorporates reproductions of historical architectural elements such as bridges. While the design scheme is concomitant with global urban development imperatives - that of improving the pedestrian and connective networks between parts of the city along the riverfront - the essential attempt to express Malaysian identity is manifest within the proposal. It remains unclear though, whether the proposal, as a finished project will be able to express such a slippery concept of cultural identity.

Ethical Issues

Firms working within the private sector are involved in the development of private golf courses, resorts, condominiums, hotels and residential projects. Identity representation and political image-making are largely out of their arena although some firms are sometimes faced with difficult ethical issues when working in regions that favour laissez fare development without appropriate controls. For instance, the office of Belt Collins & Associates in Singapore decided against involvement in designing a supposedly ‘eco-tourist’ park in Indonesia, where big game hunters could hunt rhinoceros for sport. The firm provides another example of projects raising serious ethical issues - a new town development in Irian Jaya which would have necessitated the destruction of several hectares of virgin rainforest. Indeed, staff at Belt Collins identified the trend towards short term visions for many developers caught up in the giddy rush of economic growth, with no commitment to long term environmental considerations.

Faced with developments that are ethically problematic, firms such as Belt Collins & Associates have to question the values of their profession. Three major issues emerge:

- To what extent are ethical values on land-use and development culturally derived and can there be anything approaching a global system of ethical values relating to landscape design?

- If the work of landscape architects depends upon meeting the demands of private development, what frameworks can designers draw upon to regulate the design and environmental qualities and cultural contribution of these projects if no governmental controls exist? What role can professional bodies play in addressing these issues?

- Should landscape architects use their professional standing to influence and educate clients about the possible adverse effects of particular types of development? If so, how should it be done or regulated? These are important questions for landscape architects to consider while working in newly industrialising nations where economic development can occur at a faster rate than preventative environmental policies.

Conclusion

As more landscape architects engage in long term work and adapt to localised conditions in South East Asia, complexities are emerging, fragmenting a once hopeful vision that ‘designing’ involved learning a process with the confidence that it could be applied in all situations. However, if we see ‘culture’ as a set of practices and beliefs shared by a group, we can then start to see design practice as a culturally derived process. The Malaysian examples provides ample proof that working in a different country requires revision of long established ways of operating. This implies that the practice of design can never be universalised or reduced to formula.

In this sense, we can then talk of multiple professional cultures and by looking at professional practice outside the boundaries of our own country, we can then broaden our conceptualisation of the landscape architecture profession beyond the definition set by dominant professional bodies.

The intricacies of the Malaysian political and social environment examined through the prism of design practice, allow us a glimpse into how political and economic processes determine what gets built, where it’s built, and who gets the job. The Malaysian examples are obviously easier to highlight and examine for the Western mind because of the contrast in socio political context, but the value of these examples lie also in showing us where to look for similar manifestations in our own countries. Here in Australia, these very processes are also occurring - designers in professional practice also operate within a particular culture. Tendering for jobs also involves networking, while accusations of ‘private school networks’ and ‘it’s who you know’ surreptitiously make the rounds in the industry. Designers are also influenced by political motivations, client pressure or ethical considerations. Attempts to reflect civic, cultural or national identity through design can still be the basis for design competition in the urban arena. Finally, while professional bodies still maintain and control particular ways of defining the profession, these definitions will continue to be challenged by new horizons.

Examining the intersections of culture, design, politics and economics merely confirm that designers do not merely design - they are participants in complex webs of social and political relationships that constitute professional cultures.

Thanks to

Dr. David Jones, University of Adelaide, Mr. Nik Malik, Malik Lip & Associates, KL, Mr. Phillip Vertue, Pentago, KL, Mr. Rozlan Khalid, KL, Debra Collins, Belt Collins & Associates, Singapore, Mr. Kashino Nadhiro, Landscape Architect, KL, Puan Kamariyah Kamsah, Dean, MARA.

Footnotes

-

Crouch, H.. ‘Malaysia; Neither Authoritarian nor Democratic’, in Hewison. K., Robison, R., Rodin. G. (ed.s), 1993, Southeast Asia in the 1990s Authoritarianism, Democracy & Capitalism, Allen & Unwin, Sydney. ↩

-

The economy doubled in the 1960’s and tripled between 1970-1990. ↩

-

in particular, Gomez, E.T., Political Business - Corporate Involvement of Malaysian Political Parties, 1994, Centre for SE Asian Studies. James Cook University of Nth Qld, Townsville. ↩

-

Shaw, V., Long Distance Design, in Architecture New Zealand, March/April 1994, pg 41. ↩

-

McGee, T.G. in Abel. C., Globalisation versus Localisation, Architectural Review, 196, Sep 1994, pg 4. ↩

-

Interviewed in July 1994. The developer wished to remain anonymous due to the politically sensitive nature of his comments. ↩

-

Chinese art of geomancy - where landscape and building elements are located to enhance luck and fortune. ↩

-

Kampongs mall rural village or rural settlement ↩

-

The companyc ontrolling Malaysia’s domestic oil production - also main developers of the KL Twin Towers project, the tallest buildings in the world (for the moment) designed by Argentine-born American architect, Cesar Pelli. ↩

-

Architect’s Association of Malaysia ↩

-

Malaysian Institute of Landscape Architects ↩

-

Bank BumiputraB uilding, 1980, designed by Kumpulan Akitek ↩

-

A Malay sword,s haped distinctively in a wedge like configuration. Although ‘sculptured- Modernist’ in style, the basic form of the building, designed by Hijas Kasturi Associates was inspired by the Kris. ↩

-

Kahn,J ., ‘Subalternity and the Construction of Malay Identity’, in Gomez, E. T., 1994, Political Business - Coprorate Invilvement of Malaysian Political Parties, Centre for SE Asian Studies, James Cook University of Nth Queensland, Townsville. ↩

-

A technologyp ark at Sungai Besi (Besi River), under the auspice of the Ministry of Science & Technology. ↩