High Vis Dandy was a temporary performance installation at the ‘Paris End’ of Collins Street, Melbourne, presented as part of the 2010 Next Wave Festival. At first glance, the installation resembled the familiar roadside construction site, with a ute and hi-vis clad tradies flanked by traffic barriers and a variable message signboard. Upon closer inspection, however, commuters would double-take – the construction site was actually an extreme sewing workshop! An industrial sewing machine was bolted to the back of the ute, the ‘tradies’ modelled immaculately tailored haute-couture high-vis, and the variable message signboard scrolled through sartorial puns: ‘FASHION HAZARD AHEAD’, ‘INSTALLING SILK LINING’, ‘POWER SUIT ABOVE’. Classic Aussie cock rock mashed with Parisian runway electro blasted from the ute’s speakers, forming the perfect setting for some street-side fashion appreciation.

As a public art project, High Vis Dandy sat at the periphery of landscape architecture, yet it demonstrated a mode of collaborative, intervention-based practice that could be adopted or adapted for future landscape practices.

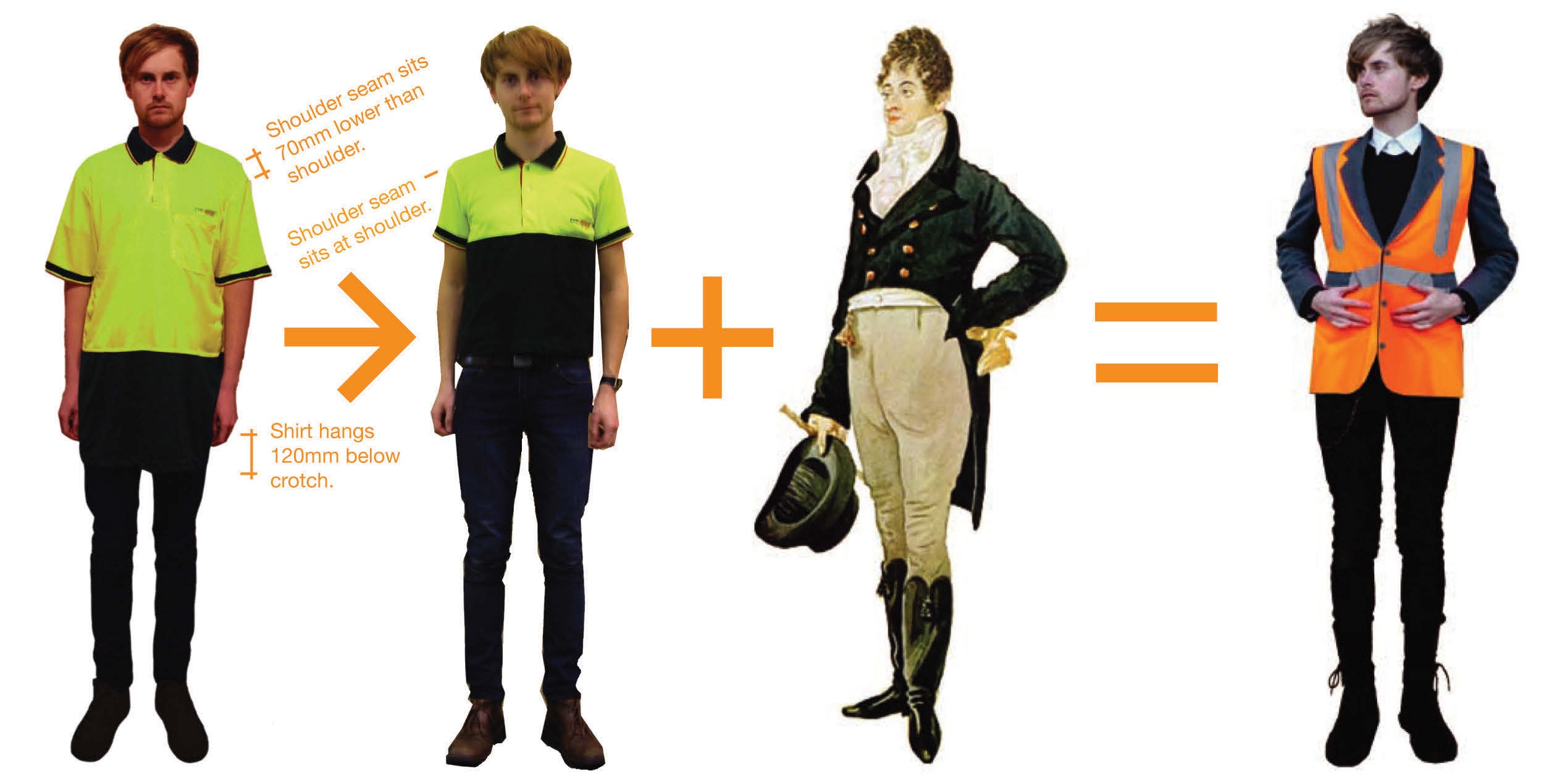

The idea for High Vis Dandy came about in 2008 as artist Matthew Kneale was undergoing a difficult six-month risk assessment process to secure a site permit from Melbourne Water, Moonee Valley City Council and Transurban/CityLink to produce a performance intervention in the Moonee Ponds Creek. Simultaneously, his courier day job had issued him with an oversized high-visibility polo shirt, which he promptly re-tailored to a more flattering fit. If our lives must be so thoroughly risk-managed, thought Kneale, and high-visibility clothing must be worn more often, we should at least be able to look good in it. Subsequently, as observation and protest, he combined the sophisticated style of Beau Brummel with AS/NZ Standards 4602:1999 compliant work-wear, and the High Vis Dandy was born.

In addition to commenting on Australia’s risk-averse corporate and political culture, the project aimed to destabilise cultural expectations of masculinity. As a young male growing up in Australia with an interest in fashion, Kneale became acutely aware of gender expectations and how masculinity is policed through social coercion such as bullying. The project engaged with these expectations spatially: from a distance, city commuters would see people in high-vis work-wear, a traditional marker of hegemonic masculinity, encapsulating physical labour, ruggedness and high-risk environments. Yet, as commuters approached, these expectations were subverted by the reappropriation of high-vis work-wear in the form of haute-couture, Regency-style costume, and the expected masculine physical labour of digging up the pavement was replaced by the traditionally feminine labour of sewing. This strategy of remixing the familiar could be useful as a mode of practice for landscape architecture, as it gives the community an opportunity to see their city and the people who occupy it with fresh eyes. As Walter Hood suggests, ‘People live in places, but they don’t see the place.’1

Image by Sarah Savage

The project was a collaboration between project director and designer Matthew Kneale, performance director Dan Koerner, performer Jess Daly and sound designer Zoe Meagher.

While each had defined roles and responsibilities, these blurred during development. For example, Meagher was encouraged to suggest performance and choreographic material, which Koerner would then integrate into the performance. While Kneale was responsible for securing permission from the various stakeholders, Daly’s charisma and fashion know-how were invaluable in convincing the Prada shop managers to allow a week-long performance to occur in front of their store. Each collaborator designed and constructed their own variation on Kneale’s original costume and performed together in the Collins Street intervention. The project demonstrates the value of embracing the diverse experiences and skills of interdisciplinary teams.

A tangential yet important component of the project’s development was a series of sewing workshops, ran by the team, at Craft Victoria. The workshops aimed to rectify the social discouragement faced by many young men who were interested in sewing. Publicity for the workshops appropriated the language of Bunnings style DIY workshops with the tagline, ‘Ever wanted to fix a rip in your work-wear or add an extra pocket?’ The deployment of this familiar language was strategic in its attempt to operate within normative gender signifiers, framing sewing as a practical skill and therefore making male participants more comfortable in attending.

Day/Night High Visibility Dandy Waistcoat by Matthew Kneale.

High-vis evolution by Matthew Kneale.

High Vis Dandy was funded by Next Wave, the City of Melbourne, Craft Victoria and the Keir Foundation. Future landscape practices could also apply for funding from local councils and festivals to test public engagement with a design concept or even use performers to enact new ways of occupying a specific place. However, any strategy of using performers to shift the way a place is occupied should be employed with caution. In 2011, the City of Melbourne attempted to teach the public how to use new tram stops with integrated bicycle lanes by employing performers dressed as lifeguards and umpires. Unfortunately, the overbearing nature of the performance simply made commuters irate. If future landscape practices are to use performance as a way of shifting the spatial and cultural etiquette of a place, then a more effective approach would be to appropriate familiar imagery specific to the site and for performers to lead by example, not by direction.

Like many contemporary art interventions, High Vis Dandy reacted against the ‘prevailing passive experience of the city’2 in its attempt to jolt city commuters out of complacency and inspire new interpretations and experiences of public space. It engaged with the performativity of the pedestrian and the specificity of the street, remixing the familiar and celebrating the temporary. Future landscape practices could find the strategy of temporary and small-scale interventions useful in testing early project ideas and, more specifically, in testing public engagement with a potential landscape design.

Image by Sara Savage

Footnotes

-

Walker Art Centre, Walter Hood Lecture, online video, 2010, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XdtIylgqP7g (accessed 16 May 2013). ↩

-

L. Feireiss, ‘Livin’ in the City: The Urban Space as Creative Challenge’, in R. Klanten and M. Hubner (eds.), Urban Interventions: Personal Projects in Public Spaces, 1st edn. (Berlin: Gestalten, 2010), pp. 2–3. ↩