Proteus, The Old Man of the Sea, whose name suggests ‘elemental’, could see the future and could tell no lies only change form, to shapeshift when attacked into dragon, bull, tree, fire, water. To vanquish him, and to force him to reveal the future, all that was necessary was to disregard his metamorphoses.

Michael Van Valkenburgh, principal of MVVA speaks about the park of the future as being ‘a protean force’ that out of necessity ‘adjusts its form to slip into urban voids that are most particularly not park areas.1

So there we have it. Primordial parks. Protean parks. Shapeshifting parks… And the need for the park.

Van Valkenburgh makes the practical necessity for parks into a virtue. He talks, quoting Bachelard, of parks as places that offer us psychological immensity. ‘City dwellers don’t just want parks; they need them so they can be connected to time and place’.2 This ability, Van Valkenburgh believes, is defining the park. Psychological immensity is ‘not really the domain of urban design as I understand it’.3 And the park satisfies a need not satisfiable elsewhere in the urban realm.

That virtuous necessity is especially critical for the future park. High density living, for the sharing of resources, for the essential minimising of our ecological footprint, requires us to ‘have places outside of our homes that offer the kind of relaxation and respite that private garden’.4 a suburbanite might get from their

The park then is an agent of social change. It is the site for colonisation, a way of creating living density, of bringing people in. ‘New parks have the potential to create new urban life at their edges, which makes them social colonisers in the formerly industrial zones of the city…5

Is this obvious? Yes, but it’s important. And the metaphor of Proteus returns here in another guise as landscape architecture itself being considered protean. The ideas that inform landscape discourse are always resurfacing in new guises, shifting in shape, one moment presented in postmodern form, the next dressed-up as Landscape Urbanism. To still the beast, to see the future, could we say? But these are all just words laid over existing practice and behold… a vanquished Proteus?

What Van Valkenburgh does so well is re-frame the issues, remind us of what is core to our landscape architectural practices. In the case of the need for parks he returns the discussion to our human need for a place to relax and imagine. It needs to be re-stated, and in a new way, and his invoking Bachelard is just to draw us in.

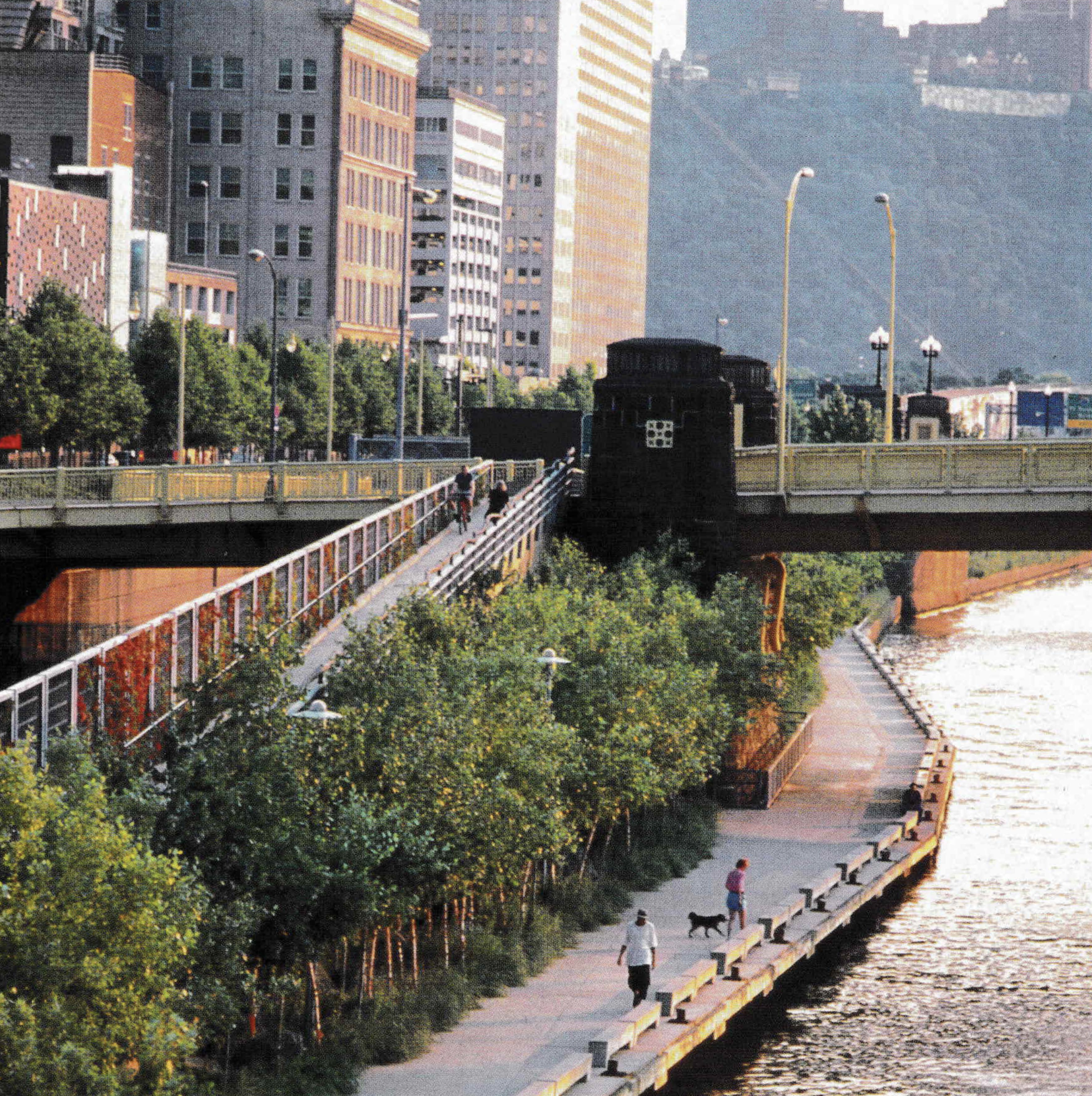

When Van Valkenburgh talks about parks as shapeshifters, or slipping into urban voids, he’s talking in particular about the post-Fordist landscape, the home territory of Landscape Urbanists. But these voids are not from the Detroit that is ‘a rather special example in which the post-industrial landscape has had an almost pathological effect in dissolving the urban structure’.6 Rather he means sites that the ‘chaos of industry’7 has left behind in cities like Pittsburgh and New York. A European might call such places terrain vague sites rather than post-Fordist sites, but that is splitting hairs. They are sites perhaps awaiting a propitious shift in the economy such as the ones that became Allegheny Riverside Park (MVVA, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, 1998) or Brooklyn Bridge Park (MVVA, New York, in progress).

Allegheny Riverside Park is made from a thin slip of land ten metres wide and half a kilometre long, accommodating an eight-metre sea wall sandwiched between a freeway and a river. It consists of two levels, one of which floods every year. The lower park level is essentially a place to be moved through and is given a more traditionally park-like quality by slight widenings in specific places.

Of Allegheny Riverside Park, Richard Weller writes, ‘First, even if it’s hard to really see it as a park in the grand democratic tradition that he places it, Valkenburgh has made a functional, generous and simply beautiful sliver of public space out of what seemed like an impossible site. Valkenburgh fattens up the river edge with a clear infrastructural intervention and breathes a naturalistic, yet urbane poetic into what was otherwise Pittsburgh’s lifeless edge’.8

‘City dwellers don’t just want parks; they need them SO they can be connected to time and place.’

Weller is not comfortable with Van Valkenburgh extending the definition of a park and prefers instead the phrase sliver of public space. Van Valkenburgh wants the term ‘park’ to be a mytheme with a thousand forms, while Weller seeks a new creature that can stand apart from the tradition to better evoke the poetry of the design. Both are reframing, both are seeking to express the newness in the design, the typological freshness. Van Valkenburgh wants to harness the power of the ‘park’, its history, its traditions, the canon of its creators, the way its meanings are deeply woven into our cultural worlds. The forces Van Valkenburgh sees as powerful are the same as those that Weller sees as constraining. What we call a ‘park’ is not just a matter of semantics. Our conception of the word influences our approach to the space.

But let us take a step back for a moment and ask ourselves if Van Valkenburgh’s protean park is anything new? Parks have always tried to resolve two different pressures -the urge for wilderness, and the urge for the social space. The conflict can be seen at Allegheny where the upper level operates as a long open plaza, with small pocket parks interspersed along its length, and negotiating those juxtapositions was one of the challenges MVA faced. JB Jackson argues that the dichotomy essentially goes back to Thoreau vs Jefferson, two competing forms of anti-urban sentiment in American thinking.’ Van Valkenburgh leans toward Thoreau with his talk of psychological immensity, man at one with ‘nature’. But his talk of the ‘cultivated park’, while showing us a site that reaffirms our relationship with nature, also shows us Jefferson’s agrarian place of the virtuous citizen. ‘Cultivation is humanity’s way of integrating the systems of the natural world into the world of urban activity…’, Van Valkenburgh says and integration is the key here …for if one sees landscape as backdrop to human activity then you accept a multitude of compromises, for instance the urban landscape that requires the application of poisons (pesticides, herbicides, fungicides) in order to look healthy… lush green lawns I wouldn’t want to sit on. The cultivated landscape creates a space for your own interaction, like a farmer or gardener rather than a bystander. This requires a greater commitment to landscape health as a principle rather than as mere image’.9

Jackson, writing in America forty years ago, concludes his essay Jefferson, Thoreau and beyond by saying: ‘All that we can do is to produce landscapes for unpredictable men where the free and democratic intercourse of the Jeffersonian landscape can somehow be combined with the intense self-awareness of the solitary Romantic. The existential landscape, without absolutes, without prototypes, devoted to change and mobility and the free confrontation of men, is already taking form around us’.10 Uncannily, this is exactly Van Valkenburgh’s protean park of the future. And he, and many others, are establishing the prototypes.

Parks have shifted their formal qualities throughout history. Now we are building parks on roofs. Now we are building green walls that function as vertical parks. Perhaps, soon, we will have air parks and space parks. And do we not fit our designs to the spaces around buildings, to the linear edges of traffic flow, to the peculiarities of topography and geomorphology and every other -ology under the sun? Don’t we shape form this park is about program, this about infrastructure, this about silence and that about the wind?

What we use to make a park is infinitely variable. The park has always a been a shapeshifter, truly protean. The important thing is that parks are a practical necessity, and this is a point that Van Valkenburgh emphasises as a virtue. It is a matter of landscape architects, as a profession, being aware that as time passes, as future opportunities become both scarcer and more critical a great openmindedness will be needed as to what can constitute a park, what will work to meet our needs. And as a society we must ask ourselves if it is any exaggeration at all to say parks are necessary for our survival.

‘Hypernature’ is another way Van Valkenburgh seeks to reframe the protean world of landscape. It is a portmanteau word for many related approaches key to his landscape style. In one form the word means ‘nature evoked, not recreated’.11 In another metamorphosis Van Valkenburgh uses it to describe jump-starting the ecologies of ‘from-scratch sites… devoid of ecological function’.12 Van Valkenburgh will shift the argument again, saying ‘Landscape architects spend too much time worrying about ‘real’ nature versus ‘constructed’ nature when both are alive and are part of the same ecological essence. There are more important issues facing us today’13 And then one more shift: he speaks of allowing a love of naturalism into his work (citing James Rose as his stimulus), as though naturalism were the key to everything.

In the case of Allegheny Riverfront Park, the lower level is meant to be responsive to flooding, allowing more and more volunteers to insinuate themselves into our planting palette as time goes by’.14 A rough rockscape provides sites for colonisation, the palette consists of the upriver species that have proven themselves suitable to the conditions beeches for instance these are the ‘volunteers’ he refers to. At Allegheny, the site is so thin, there is no room for a floodplain, and so what has been made is exaggerated nature, supported by exaggerated hi-tech soils. The exaggeration also works as a response to the scale and dimension of the space, ‘thickening’ the experience on a site unsuited to the expansive requirements of the pastoral. At Allegheny a contrast is made between the ‘wilfully wild and the intentionally urbane’.15

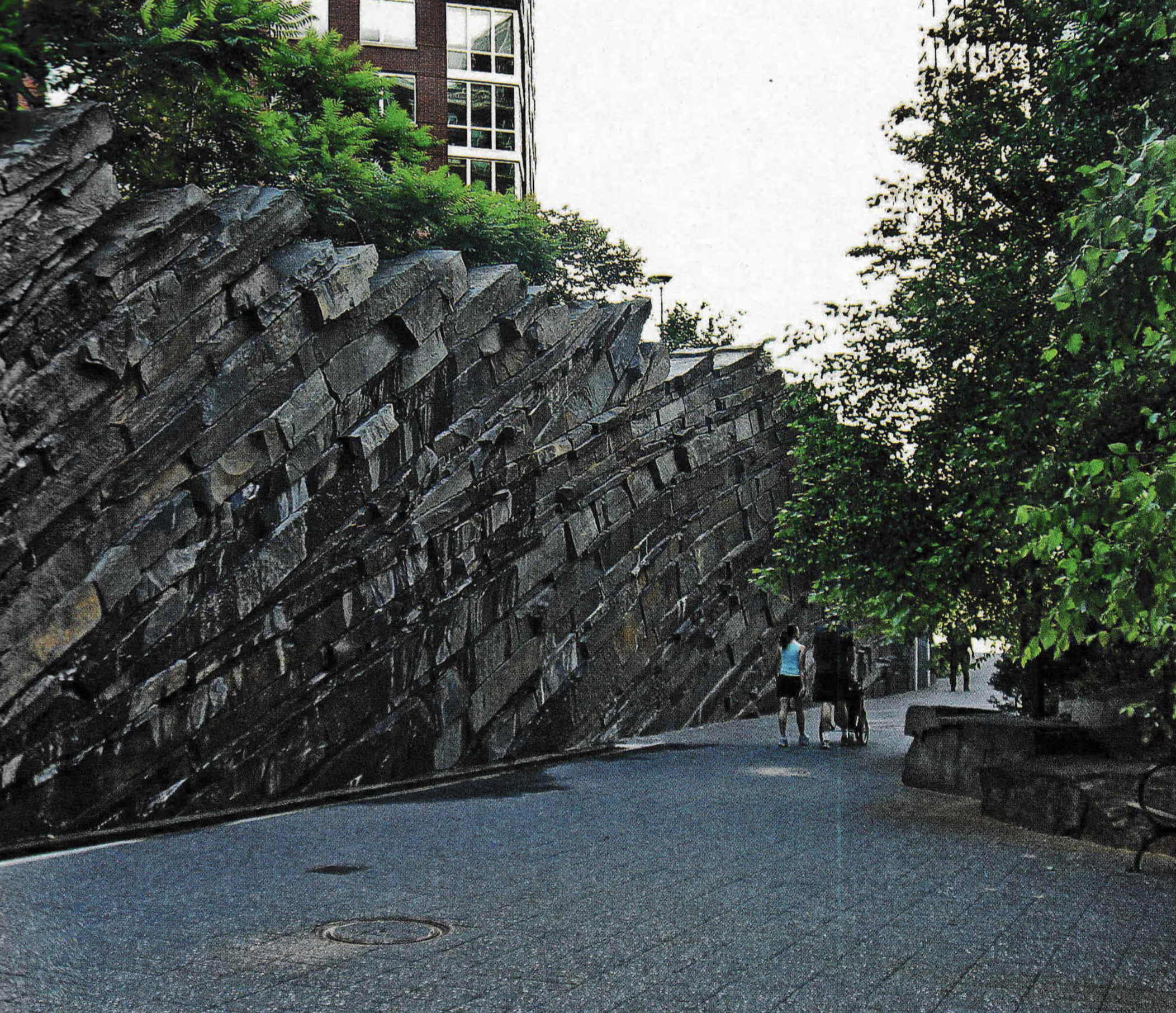

In Teardrop Park in New York a carefully sequenced experience, thick with rich planting the sublime is made manifest through a vast and sculptural anticline of a stone wall that abjectly weeps in summer and carries an ice fall in winter. The rock wall orchestrates the division of the site into open and closed. ‘Our desire was to use a geological metaphor to create a hyper-articulated physical experience… to bring a tension out between the built and the natural’.16

Closer to home, and away from MVVA projects, Federation Square in Melbourne is another example of hypernature at work, the stone sett surface miraculously evoking a rolling landscape while being an artificial topography built on a podium over the erased topography of the pre-settlement Yarra River. Hypernature is nature idealised and re-presented. ‘It makes me think of music and painting informed by borrowing and reassembling of material essences’.17 It is the designer’s poetic or phenomenological understanding of essences first and foremost. Olmsted did it. Everyone does it. It’s obvious, but important, and needs to be re-stated in new ways.

Shapeshifting, psychological need, hypernature: these are all important issues core to landscape architecture that deserve to be constantly re-presented in discussions of our practice. Van Valkenburgh is expert in making those reframings and of making them a virtue.