The representation of the metropolis in various media has had at its disposal one particularly privileged instrument since its beginnings: photography. Generated by technological apparatuses dating from the period of the expansion of the great cities, images of Paris, Berlin, New York, and Tokyo and of the inhabited continuums of the first, second, and third worlds have entered our memory and our imagination by way of photography. Landscape photography, aerial photographs, and photographs of buildings and of the people living in big cities constitute a principal vehicle for information that makes us aware of the built and human reality that is the modern metropolis.

Photography’s technical and aesthetic development has seen the evolution of different sensibilities in relation to the representation of architecture, to the point where it has become impossible in recent years to separate our understanding of modern architecture from the mediating role that photographers have assumed in this understanding. The manipulation of the objects captured by the camera - framing, composition and detail have decisively influenced our perception of the works of architecture photographed. It is impossible to imagine a history of 20th- century architecture that would not refer to specific architectural photographers. Even our direct experience of the built object cannot escape the mediation of photography. It would thus be meaningless to evoke some Manichaean idea of a direct, honest, authentic experience of buildings, against which to set the manipulated perverse other of the photographic image.

The same is true of the city. Not only is the possibility of accumulating direct personal experiences problematic in places in which one has not lived for a long time, but our gaze has been constructed and our imagination shaped by photography. Of course we also have literature, painting, video, and film, but the imprint of the photographic (that ‘minor art’ as Pierre Bourdieu would have it) continues to be primordial for our visual experience of the city. During the years of the metropolitan project, of its theorization and of the propaganda presenting the great city as the indispensable motor force of modernization, photography played a decisive role. The photomontages of Paul Citroen, Man Ray, George Grosz, and John Heartfield set out the accumulation and juxtaposition of great architectonic objects as a way of explaining the experience of the big city.

As Rosalind Krauss has shown, photography operates in semiological terms not as an icon but as an index. Photography’s referent has no immediate relation, as a figure, to the forms produced by photography. No formal analogy makes transmission of the photographic message possible. Rather, this occurs through the physical proximity of the signified and its photographic signifier. When we look at photographs, we do not see cities - still less with photomontages. We see only images, static framed prints. Yet by way of the photographic image we receive signals, physical impulses that steer In a particular direction the construction of an imaginary that we establish as that of a specific place or city. Because we have already seen or are going to see some of these places, we consume this semiological mechanism of communication, and the memories that we accumulate through direct experience, through narratives, or through the simple accumulation of new signals produce our imagination of the city.

After World War II, photography developed a system of signs completely different from that of the density of the photomontage. We could call this the humanist sensibility of urban narratives constructed from images of anonymous individuals in settings devoid of architectonic grandiloquence. ‘The Family of Man’, an exhibition organized by Edward Steichen at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1955. was produced after the Magnum photo agency had initiated the ‘existentialist’ reading of the city and landscape (which reached its apotheosis in Robert Frank’s 1962 book The Americans). Yet the phenomenon that interests me here dates from the 1970s, with the inauguration of quite another sensibility that directed yet another gaze on the big cities.

Air balloon photographs of Sand Belt site by Herbert Bauer.

Empty, abandoned space in which a series of occurrences have taken place seems to subjugate the eye of the urban photographer. Such urban space, which will denote by the French expression terrain vague, assumes the status of fascination, the most solvent sign with which to indicate what cities are and what our experience of them is. As does any other aesthetic product, photography communicates not only the perceptions that we may accumulate of these kinds of spaces but also the affects, experiences that pass from the physical to the psychic, converting the vehicle of the photographic image into the medium through which we form value judgments about these seen or imagined places.

It is impossible to capture in a single English word or phrase the meaning of terrain vague. The French term terrain connotes a more urban quality than the English land; thus terrain is an extension of the precisely limited ground fit for construction, for the city. In English the word terrain has acquired more agricultural or geological meanings. The French word also refers to greater and perhaps less precisely defined territories, connected with the physical idea of a portion of land in its potentially exploitable state but already possessing some definition to which we are external.

The French vague has Latin and Germanic origins. The German Woge refers to a sea swell, significantly alluding to movement, oscillation, instability, and fluctuation. Two Latin roots come together in the French vague. Vague descends from vacuus, giving us ‘vacant’, and ‘vacuum’ in English, which is to say ‘empty, unoccupied’, yet also ‘free, available. unengaged’.

The relationship between the absence of use, of activity, and the sense of freedom, of expectancy, is fundamental to understanding the evocative potential of the city’s terrains vagues. Void, absence, yet also promise, the space of the possible, of expectation.

A second meaning superimposed on the French vague derives from the Latin vagus, giving ‘vague’ in English, too, in the sense of ‘indeterminate, imprecise, blurred, uncertain’. Once again the paradox of the message we receive from these indefinite and uncertain spaces is not purely negative. While the analogous terms that we have noted are generally preceded by negative particles (in-determinate, im- precise, un-certain), this absence of limit precisely contains the expectations of mobility, vagrant roving, free time, liberty.

The triple signification of the French vague as ‘wave’, ‘vacant’, and ‘vague’ appears in a multitude of photographic images. Recent photographers, from John Davies to David Plowden, Thomas Struth to Jannes Linders, Manolo Laguillo to Olivio Barbieri, have captured the condition of these spaces as internal to the city yet external to its everyday use. In these apparently forgotten places, the memory of the past seems to predominate over the present. Here only a few residual values survive, despite the total disaffection from the activity of the city. These strange places exist outside the cities’ effective circuits and productive structures. From the economic point of view, individual areas, railway stations, ports, unsafe residential neighbourhoods, and contaminated places are where the city is no longer. Unincorporated margins, interior islands void of activity, oversights, these areas are simply uninhabited, unsafe, unproductive. In short they are foreign to the urban system, mentally exterior in the physical interior of the city, its negative image, as much a critique as a possible alternative.

Contemporary photography does not fix on these terrains agues innocently. Why does this kind of landscape visualize the urban in some primordial way? Why does the discriminating photographer’s eye no longer incline toward the apotheosis of the object, the formal accomplishment of the built volume, or the geometric layout of the great infrastructures that constitute the fabric of the metropolis?

Air balloon photographs of Sand Belt site by Herbert Bauer.

Why is this landscape sensibility potentially unlimited with regard to this artificial nature populated by surprises, devoid of strong forms representing power?

The Romantic imagination, which still survives in our contemporary sensibility, feeds on memories and expectations. Strangers in our own land, strangers in our city, we inhabitants of the metropolis feel the spaces not dominated by architecture as reflections of our own insecurity, of our vague wanderings through limitless spaces that, in our position external to the urban system, to power, to activity, constitute a both a physical expression of our fear and insecurity and our expectation of the other, the alternative, the utopian, the future.

Odo Marquand has characterized the present as ‘the epoch of strangeness in front of the world’. That which characterises late capitalism, the leisure society, the post-European era, the postconventional epoch is the fleeting relationship between the subject and her/his world, conditioned by the speed with which change takes place.

Changes in reality, in science, in behavour, and in experience inevitably produce a permanent strangeness. The exposure of the subject and the loss of consistent principles correspond ethically and aesthetically. Following Hans Blumberg, Marquand reorients his analysis around a posthistorical subject who is, fundamentally, the subject of the big a city: a subject who lives permanently in the paradox of constructing her/his experience from negativity. The presence of power invites one to escape its totalizing presence; safety summons up the life of risk; sedentary comfort calls up shelterless nomadism; the urban order calls to the indefiniteness of the terrain vague. The main characteristic of the contemporary individual is anxiety regarding all that protects him from anxiety, the need to assimilate the negativity whose eradication is seemingly the social objective of political activity.

In confronting simultaneously the perception of the messages that reach us through our openness to the world and the resulting behaviours, Marquand, thinking along the general lines of radical post-Heideggerian hermeneutics, seeks to transcend the split between aesthetics and ethics, between experience of the world and action on the world.

Marquand’s ‘epoch of strangeness in front of the world’ picks up on the Freudian theme of the unheimlich as glossed in recent years by those who have sought in the individual experience of dislocation and displacement the starting point for the construction of a politics. In Etrangers a nous- memes (Strangers to Ourselves), Julia Kristeva sets out to reconstruct the problematics of alien status in the public life of advanced societies. This discourse, directed at understanding the xenophobia danger- ously on the rise in Europe, takes the form of a philosophical text concerning the meaning of the other, of that which is radically strange and alien. Kristeva, in her tour of the great landmarks of Western culture, from Socrates to Augustine and from Diderot to Hegel, returns to the Freudian text that takes the strangeness of contemporary men and women as their strangeness to themselves. Freud points out the radical impossibility of finding oneself, of locating oneself, of assuming one’s interiority as identity.

This theme of estrangement, from the political perspective of an increasingly multicultural Europe with its conflicting nationalisms, with the rebirth of particularisms of all kinds, also ultimately leads from the political to the urban discourse. From the polis to the urbs, Francoise Choay has said, and from the notion of belonging to a collective to an identification with race, colour, geography, or any kind of group. Strangers to ourselves reveals the individual as carrier of an internal conflict between his/her conscious and unconscious, between helplessness and anxiety. Not the individual endowed with rights, liberties, and universal principles, not the subject of the Enlightenment and of the Declaration of the Rights of Man, on the contrary, here is a politics for the individual in conflict with himself, despairing at the speed at which the whole world is transformed yet aware of the need to live with others, with the other.

Air balloon photographs of Sand Belt site by Herbert Bauer.

The photographic images of terrain vague are territorial indications of strangeness itself, and the aesthetic and ethical problems that they pose embrace the problematics of contemporary social life. What is to be done with these enormous voids, with their imprecise limits and vague definition? Art’s reaction, as before with ‘nature’ (which is also the presence of the other for the urban citizen), is to preserve these alternative, strange spaces, strangers to the productive efficiency of the city. If in ecology we find the struggle to preserve the unpolluted a spaces of a nature mythicized as the unattainable mother, contemporary art seems to fight for the preservation of these other spaces in the interior of the city. Filmmakers, sculptors of instantaneous performances, and photographers seek refuge in the margins of the city precisely when the city offers them an abusive identity, a crushing homogeneity, a freedom under control. The enthusiasm for these vacant spaces - expectant, imprecise, fluctuating - transposed to the urban key, reflects our strangeness in front of the world, in front of our city, before ourselves.

In this situation the role of the architect is inevitably problematic. Architecture’s destiny has always been colonization, the imposing of limits, order, and form, the introduction into strange space of the elements of identity necessary to make it recognizable, identical, universal. In essence, architecture acts as an instrument of organization, of rationalization, and of productive efficiency capable of transforming the uncivilized into the cultivated, the fallow into the productive, the void into the built.

When architecture and urban design project their desire onto a vacant space, a terrain vague, they seem incapable of doing anything other than introducing violent transformations, changing estrangement into citizenship, and striving at all costs to dissolve the uncontaminated magic of the obsolete in the realism of efficacy. To employ a terminology current in the aesthetics underlying Gilles Deleuze’s thinking, architecture is forever on the side of forms, of the distant, of the optical and the figurative, while the divided individual of the contemporary city looks for forces instead of forms, for the incorporated instead of the distant, for the haptic instead of the optic, the rhizomatic instead of the figurative.

Our culture detests the monument when the monument represents the public memory of power, the presence of the one and the same. Only an architecture of dualism, of the difference of discontinuity installed within the continuity of time, can stand up against the anguished aggression of technological reason, telematic universalism, cybernetic totalitarianism, and egalitarian and homogenizing terror. Three different images of a single place at the centre of a great European metropolis - the Alexanderplatz in Berlin provide an example of the multiple ways in which we treat the terrain vague. The most recent image comes from the post-Stalinist years of all-embracing state power. It is Big Brother’s rendering of the modern utopia. The form of the place is no more than the a repetition of a universal, radically generic ordering through which the geometry of the buildings, the paving of the public space, and the square are consolidated as a constructed principle. Here, in theory, the rights of the modern citizen, the tireless worker, find the setting for their abiding happiness. What results is, in fact, the space of horror, of the primacy of the abstractly political converted into absolute dominion.

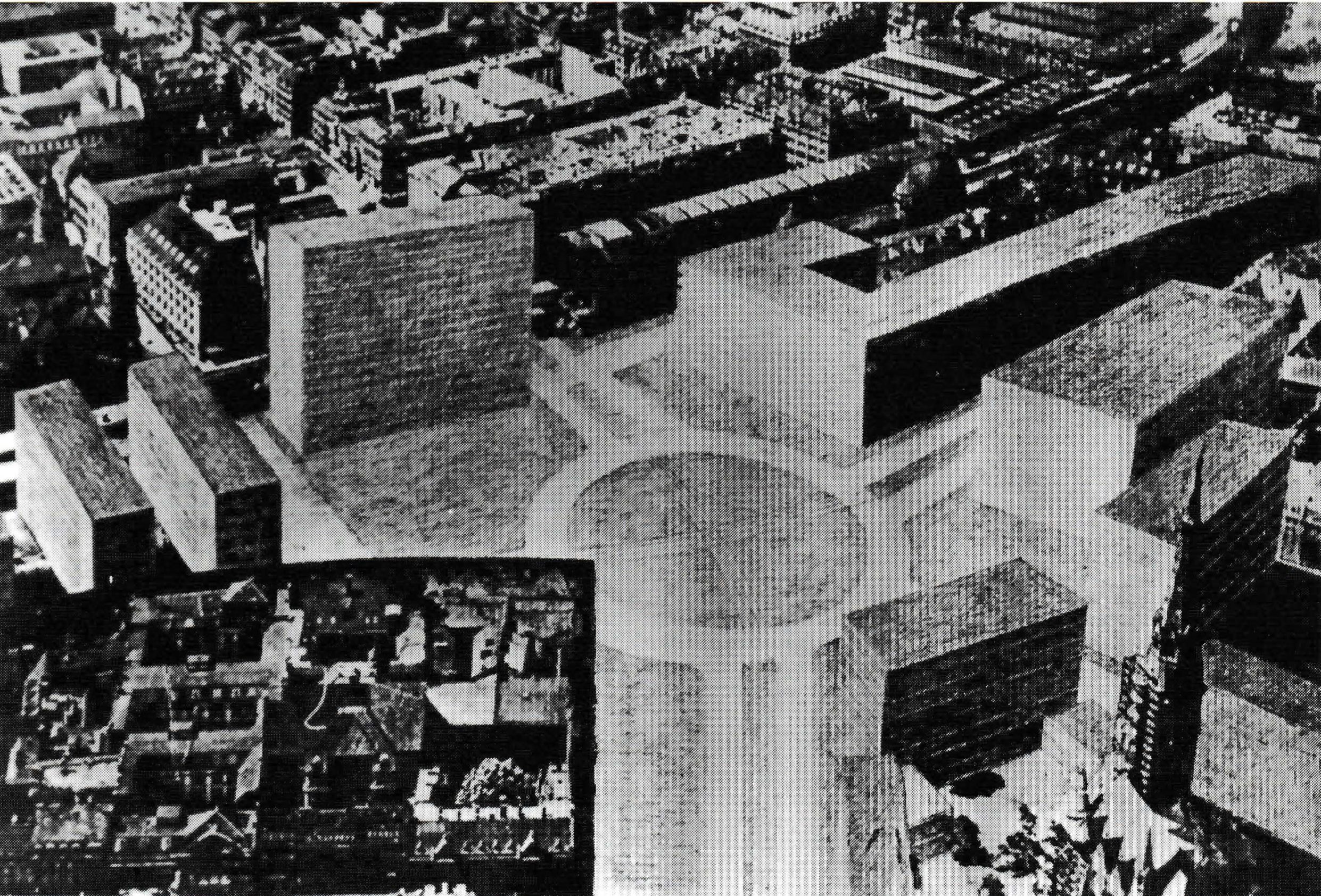

Mies van de Rohe’s scheme for the Alexanderplatz Mies van de Rohe, a Critical Biography. Schulze, Franz.1985

The second image shows the Alexanderplatz in 1945, after its sustained bombing by the Allied air forces. It reveals the disfigured city, the dislocated space, the void, imprecision and difference. An urban space becomes a terrain vague through the violence of war. The contradiction of war brings to the surface the strange, the indescribable, and the uninhabitable. The third image, while earliest chronologically, is last in this intentionally antichronological sequence. In Mies van der Rohe’s 1928 photomontage of a project for Alexanderplatz there is action, production of an event in a strange territory, the casual unfolding of a particular proposal superimposed on the existing, repeated void on the void of the city. This silent artificial landscape touches the historical time of the city, yet neither cancels nor imitates it. Flow, force, incorporation, independence of forms, expression of the lines that cross the city - all find expression in Mies’s visionary plan. It is beyond art that unveils new freedoms. It goes from nomadism to eroticism.

Today, intervention in the existing city, in its residual spaces, in its folded interstices can no longer be either comfortable or efficacious in the manner postulated by the modern movement’s efficient model of the enlightened tradition. How can architecture act in the terrain vague without becoming an aggressive instrument of power and abstract reason? Undoubtedly, through attention to continuity: not the continuity of the planned, efficient, and legitimated city but of the flows, the energies, the rhythms established by the passing of time and the loss of limits. Marquand proposes the notion of continuity in contrast to the clarity and distinctness with which the strange world presents itself to us. In the same way, we should treat the residual city with a contradictory complicity that will not shatter the elements that maintain its continuity in time and space.

Reprinted from ‘Anyplace’, Cynthia C. Davidson (ed.), the MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, with the permission of the publisher and author.