Fourteen years ago, Steven Krog wrote in an article entitled ‘Creative Risk-Taking’ (Landscape Architecture, May 1983) that:

To learn how landscape architecture is made today, one must study the machinations of its nearly deified design process. Certainly there is no denying the essentiality of a methodological analysis of programme, site and their fit. After all, the landscape is a much-varied entity, difficult to understand and manipulate.

Which, one might have thought, is pretty self-evident.

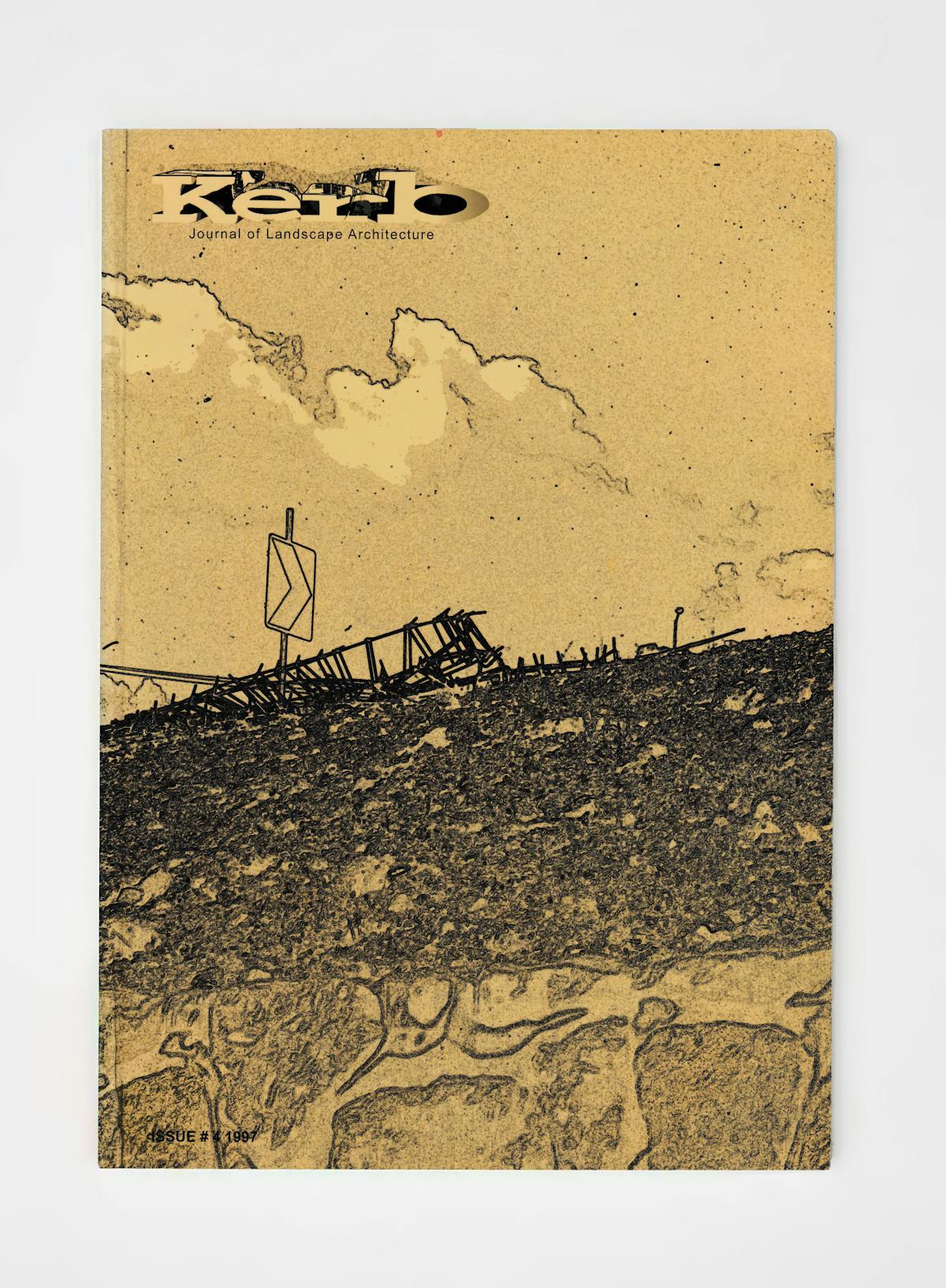

The first offering in this issue of Kerb is an explanation of Andrea Kahn’s ‘site analysis myth’, which shows that it is not. Her views on the perceptual education of design students finds parallels in the comments of Christophe Girot in another article — ‘Let your guts speak’.

The containment and resolution required of built projects is not easy. The most obvious containers are budgets and the resolutions chiefly ones of economic viability. Communicable precision is necessary to enable the pieces to fit together, while a common understanding collapses differences. Does it collapse anything else?

In the effort to exercise a denial of closure, results sometimes appear as an uneasiness characterised by effectively hedging one’s bets. Ideally the effort is a more artful, generative embracing of ‘the other’ which stimulates new thought by disingenuous juxtaposition. Such raw connections are the fertile occasions of revelation — and of very funny jokes.

‘The other’ are the ethnic, religious and social minorities of our culture, easily identified in many talks given at the Australian Institute of Landscape Architects conference ‘96. The other as a particular quality of local variation is also identified in the influence on Australian culture of design internationalism, and the world exposure we received through the 1956 Melbourne Olympics — a point made in discussion of the Museum of Modern Art exhibition in ‘The Garden 1956’. The assessment of this regionalism as a cringing inadequacy, is speculated by queries raised as to the design opportunities of the Sydney 2000 Games in ‘Millenarianism’.

Landscape architects are familiar with the other as the ‘ground’ upon which the architectural ‘figure’ has appeared as a dominant oppressor. The ‘word’ is the figure elect and expectant. Tim Nicholas challenges the terrain vague of suggestive urban abandonment explored in the last issue of Kerb. Even indistinct, useless terrain is presumed conquered by tagging it. It is permitted to be strange. It is not permitted to be less strange to anyone else, or occupied in a different, equally valid way. Papadakis makes the point in his own way.

Leone Sandercock’s ideal ‘city’ is civilising because it is a space where strangers — others — meet equally. ‘A-political Projections’ is a competition entry predicated on a site design which accepts all imprints. It is a ‘level’ playing field of everyone’s mounded pound of flesh — container loads of native soil. All power is constantly contested, mutated and made aware.

It appears that architectural (in which I include landscape architectural) critique is frustrated and fascinated by its inability to securely isolate the basic building block of intentional meaning. It can not locate the cornerstone of a constructed ‘sense of place’. Instead, it finds not just a substitute, but an analogy, in its adoptive quest for ever more precious, digitally accurate and immemorable units — that is, in ‘analysis’. Given the infinite possible perceptual variations, and the finite requirements of assessment, our explanations can only pretend detachment from our desires. This is the simplest entry to the labyrinthine truth that question already carries its own answer.

Criticism, like analysis, is subjective — and useful because it is. The only negative criticism is actually that which is erroneously objective. We all know that ‘power’ is made manifest in form, but it is only effective when measured against change. Julian Raxworthy’s Hong Kong Monument competition entry references this recognition. The final quotation in Nick Wong’s assessment of Melbourne’s Town Hall Plaza development illuminates a concern, not so much with the manifest power of a commercial enterprise physically annexing the public Plaza, but with a loss of the space’s potential to be other things. ‘Free’ social space (commercial or not) is productive in ways that far outweigh the costs of securing its own production — but which are essentially uncontrollable.

It is possible to see in the articles of this issue, a consideration of critique and design revolving irresistibly around a repositioning of the obvious. It is not enough to ‘learn how landscape architecture is made today’ we need to make use of learning to imagine how it may be made tomorrow — and why. Design may be verifiable, but it might seem better that it were believable.

In editing this issue, I have come to recognise some of the discomforts of repositioning. There is something exquisite, and shockingly practical, in the multiplicity of painful variations available to the careful, sensitised designer. The landscape is full of barbs and nettling, nested traps to trip us up. hope all our readers will find something to scratch themselves with in the following pages.

This issue of Kerb is dedicated by its Team to Anne T. Pettus with gratitude.