Initially intended as a forum for publishing papers delivered at W.EDGE, the 1997 Student Landscape Architecture Conference, Kerb 6 has evolved to its present format, which whilst included some conference material, has been extended to embrace a continuing exploration of the three key ideas of the conference namely Site: Indicator or Obstacle for (Mis) Information; Australia: A Collision of Lines; and Theory: Practice and History. These ideas have been used notionally as a ‘gathering device’ for information, however as evident from the way in which many of the articles address issues across concepts, they are not mutually exclusive. With its contribution of a provocative collection of articles, Kerb 6 not only sustains the questioning spirit of the W.EDGE conference, but also maintains the journal’s valuable role in deconstructing the “status quo”.

The first event of the W.EDGE conference was a radio conversation responding to Richard Weller’s paper A Rubric of Place, recently published in Kerb 5. Kerb 6 continues the conversation with response to Weller’s paper as broadcast by Radio National in September ‘98. Taking part in the response were Professor George Seddon, Professor Stephen Muecke and Dr Richard Read. The conversation is presented in this publication as a symbolic continuous thread weaving through the body of the journal, linking both the conference and Kerb 5, to Kerb 6.

Another version of a continuous conversation can be seen in the lament expressed frequently in discussions of the development of landscape architecture. The lament in its apparent lack of direction, its undefined position and its subordination to associated disciplines of architecture, engineering and more recently to artists, who have taken their canvases off the wall and melded them into sites.

Daniel Firns, in The Terrain in the Machine; the Ghost in the Terrain, suggests that the middle ground traditionally occupied by the garden can appropriate the technology middle ground occupied by the machine in the design process. In the middle ground of cyberspace, Homo sapiens become Homo cyborgs and in so doing are able to access new orders of complexity and new degrees of abstraction thus reinvigorating or perhaps redirecting the design process.

Describing landscape architectural practices as a site of paranoia Helen Armstrong also recognises the latent potency in the ‘middle ground’ or ‘the space in between’. Her article Vibrant Cosmopolitanism or Understated Australian: Australian Landscape Practice in the ‘Space-in-Between’ establishes a context for recognising and appreciating the strength inherent in the landscape forms of the ‘cosmopolitan Australian’ and the ‘understated Australian’.

Probing the design process Peter Connolly alerts us to the power and the horror of the GAP between site and representation, suggesting that conventional landscape design representations are over determined and that designers could look to bricoleur, the art or bricolage and the idea of catastrophe as possible ways of thinking about how to design.

In a gap of quite different nature Rod Barnett presents the Whakarewarewa Thermal Reserve as a Landscape of Simulation. Barnett describes how in New Zealand, colonisers and Māoris equally complicit in commodifying the coveted spirituality of Indigenous cultures, have manufactured a landscape experience that offers primitivism as a nostalgic journey to the past.

The Anglo-European propensity for misreading colonised landscapes and indigenous culture is also taken up by Hugh Webb, Martin Thomas and Catherine Kohn.

In Colonised Landscape: Decolonised Country, Webb describes the indigenous interconnectivity with country, suggesting that only by developing a similar way of reading landscape will we start to breakdown the persistence of colonial perception. Tracing the migration and endemic persistence of colonial perception, Thomas critiques the paintings of Eugene con Guard and journals of geologist explorer Paul Strzelecki. Although not central to his thesis, Thomas makes mention of Strzelecki’s monumental map, some twenty-five feet in length, five feet in width and scaled at a quarter inch to the mile. This, I have no doubt, will raise some eyebrows of appreciation among practitioners who maintain the practice of manual rendering as opposed to machine graphics.

Departing from the exposure of historic misreading, Kohn addresses potential mis-readings for designers involved in remote Aboriginal community projects. Kohn’s paper, resulting from several years’ experience with remote communities outlines very useful strategies from establishing effective community between design professionals and remote Aboriginal communities.

Equally appreciated are the visual essays of Jon Tarry, Andrew Saniga and Jesse Marlow, and Richard Woldendorp and images from the graduating folio of UWA student, Neil Moncreif. Tarry questions perceptions of sight and site, Woldendorp’s images capture the enduring and endearing quality of the Australian landscape seen from a distance while Saniga and Marlow reveal an equally powerful and yet ephemeral landscape borne of insurrection.

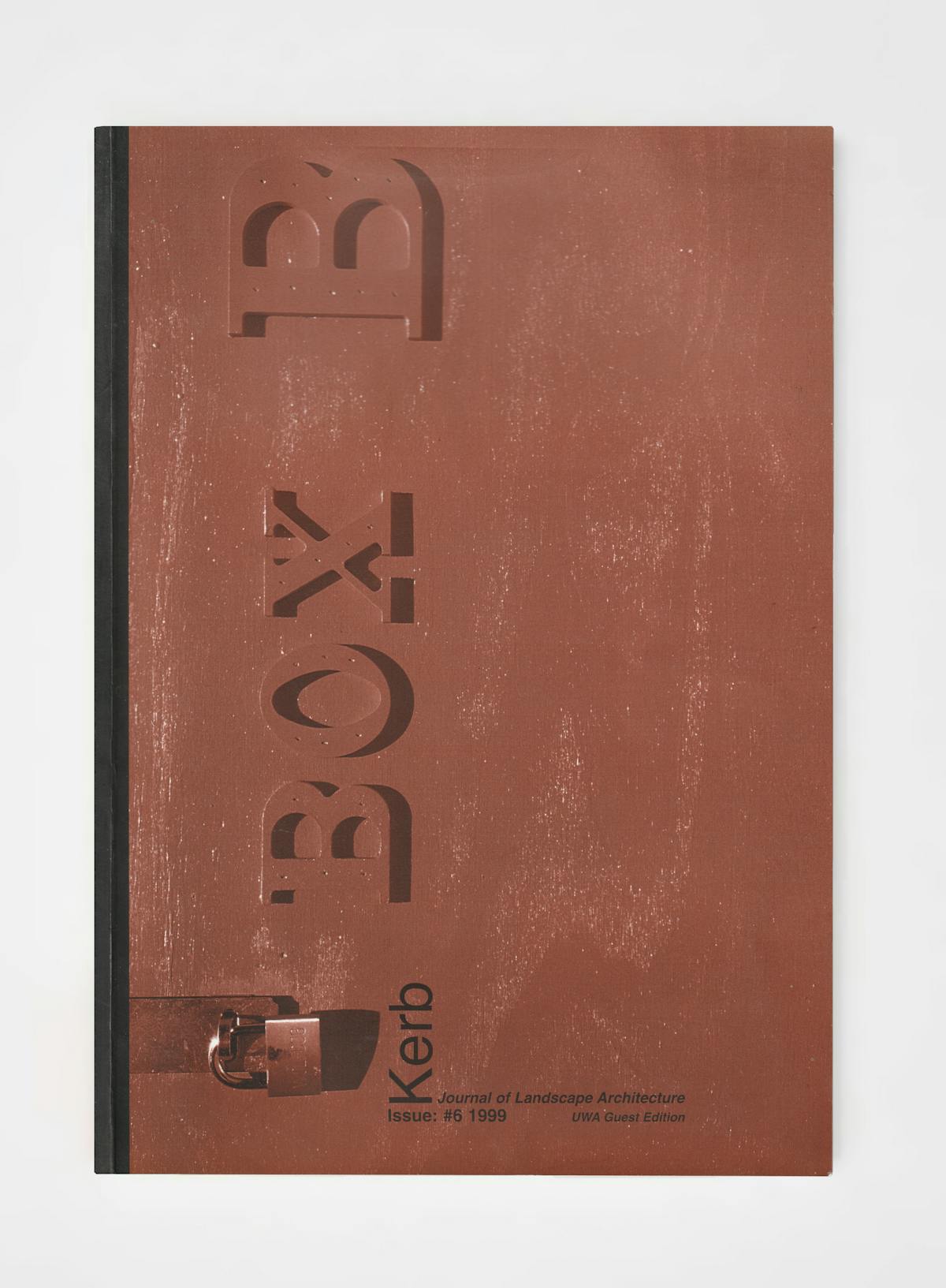

Kerb 6, is the inaugural ‘guest edited’ edition of the journal, and as editor, I have welcomed the opportunity of contributing to the continuing discourse of landscape architectural theory and practice. I would like to thank Richard Weller of UWA and Cath Stutterheim, a previous editor of Kerb, for facilitating this opportunity. I would also like to thank Simon Anderson Head of School and the staff of the UWA School of Architecture, Fine Arts and Landscape Architecture for their support in this endeavour. Finally, my thanks to co-worker Damien Pericles for his time, support and indispensable creative graphic skills in realising Kerb 6.