Clarity

Street cleaners are perceived as a rudimentary maintenance system and nothing more. Why do they only come out at night? It’s probably out of convenience more than anything else. It would be most frustrating trying to clean a sidewalk while millions of leather, rubber, wooden and metal soles traipse its surface. Soles belonging to those accustomed to a city of hidden regiments, repetitive scenery and shortcut solutions. Soles consumed by sameness, apparently indifferent about their urban lot. Yet without these sedated soles, there is no city. So the street cleaners become nocturnal beasts, though their loud flashing nature is hardly suited to it, giant mechanical toothbrushes scrubbing the city’s concrete teeth, racing up and down in a hidden and cumbersome effort to remove the plaque of the day before the soles return with the light.

What a weird idea… a city with teeth. Take it if you want; it’s not ours.

PlastiCity FantastiCity extinguishes the corrupt attitude currently stunting landscape architecture’s growth; the attitude that having an idea means it belongs to you. The attitude that makes you grasp good ideas jealously, as if they are precious. When we acknowledge that our contributions should be part of a much larger collaboration, we will begin to see landscape architects assume less selfish ownership for their designs.

An idea can outlive a thousand generations of designers. When you have taken a concept to the brink of its sanity, leave it there for someone else to find.

PlastiCity FantastiCity creates new conceptual opportunities through hyper-escalating present issues, whether they concern urban growth depleting resources, micro-scale initiatives, self-induced chaos or the important role of notional aspects within them. Thus hyper-escalation forces us to break through the conventional standards of design, whether they are systematic or representational, taking us to new unfathomable realms. We must fight sameness with speculative collaboration, ensuring that landscape architecture does not go on, lazy and unchallenged, but evolves in daring and feverish ways.

A city with teeth. Why the hell would a city have a mouth?

Sameness is rapid, it is contagious, and it produces an inconceivable number of demands. One demand we can observe and which has gained terrifying momentum, dates back to at least 1908 when Henry Ford unleashed the Model-T upon the world. Today, more than 600,000,000 passenger cars travel the roads of the world. By 2020, this number is expected to reach one billion.

“Any colour, so long as it’s black!” Ford announced proudly from his podium.

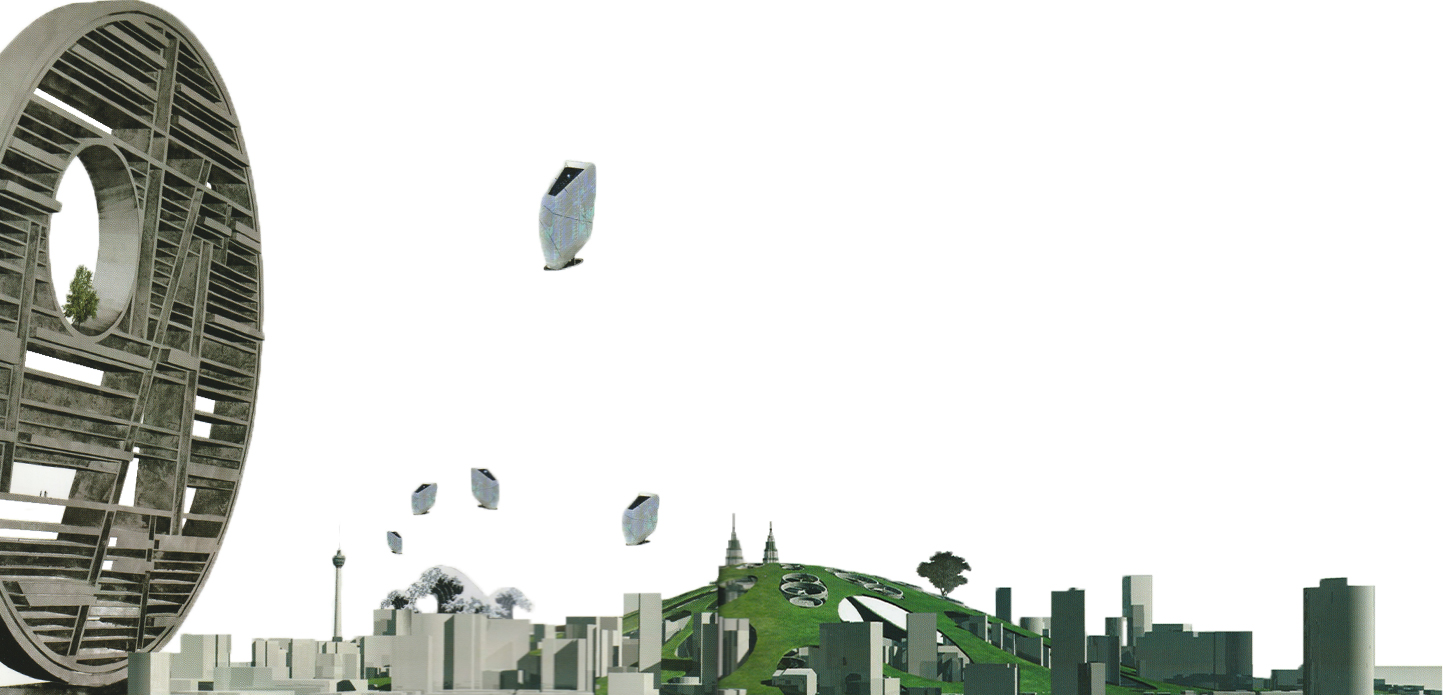

How many kilometres of road will we need to facilitate one billion vehicles? Even before one kilometre becomes congested, another is built, identical to the original. When it becomes subject to lockjaw traffic another identical road is built. And so on. Roads are constructed from concrete and metal and are a stagnant example of mankind’s ability to replicate sameness, but what happens when we don’t need roads anymore? As technologies change, there will come a time when vehicle numbers drop as resources deplete, or public transport finally becomes effective. What do you do with four generations of obsolete roads? More to the point, what would a landscape architect do with them? If our profession is to render significant change or validation, we must not let our design be hindered by our times or our technologies. We must acknowledge these future issues as being our domain of design.

By approaching design though hyper-escalating relevant fabrics, we must ignore conventional standards when justifying out position. If we want to design unconventionally, why would conventional standards be appropriate? Mitchell Joachim takes on the massive problems associated with our personal automotive culture in Pre-Source. To address the problems of depleting resources, Joachim proposes to retrofit American houses with giant caterpillar treads so they can roam the obsolete roads of the future.

“Why should we put further energy into inferior patterns from the past? shouted Joachim from the steering wheel of his two-storey house, leading a convoy of other houses downtown.”

The concept is unfathomable. Houses cannot be driven like cars … yet. This is where Joachim demonstrates an understanding of the crucial link between a shift in attitude and a notational design that exceeds current technology. When most of America’s roads are obsolete, the knowledge needed to effectively retrofit houses will exist, and when it does, Joachim’s contribution will persist well beyond his lifetime. Today it is impossible, yet in the eyes of PlastiCity FantastiCity if it more logical and brilliant than discarding the roads that took generations to build. And when Joachim’s caterpillar house become too abundant and eventually obsolete, someone will find a wat to build on the fantastic ideas he left them. This is how PlastiCity FantastiCity years to see landscape architecture operating within the world: designing without ownership and sharing concepts that move beyond our times and technological boundaries.

But alas, ‘contemporary landscape architecture’, as it is so often referred to, is barely more than a green lipstick, painted onto cities as an aesthetic. It is the manicured lawns that deny you a seat. It is the regiment of trees that watches you from the sidewalk, giving the illusion of environmental consideration. It is the more attractive feature spaces which do little more than perpetuate the stereotype that we are gardeners. Landscape architecture has drifted too far into being business as usual, when once it was motivated by speculative design that inspired futuristic endeavours. We’re not trying to reignite a discussion of utopian living, but when Le Corbusier proposed Ville Contemporaine in 1922, no-one believed it would ever reach construction. Yet now, the skyscraper which was once thought impossible defines our contemporary cities. Consider a modern day impossibility. One day it will exist. But only if we design it now. James Corner took this idea, but chose to physically manifest it. So did Peter Latz, more than ten years ago.

The projects are dated, but Highline and Landschaftpark Duisburg-Nord are examples of landscape architecture that adapts failed urban city fabric, preventing more pointless waste and consequently more repetitive construction. Despite success they were not taken far enough. Our cities have eaten too much of the same thing for too long. If their diets aren’t varied, the plaque won’t scrub off. It is the business of landscape architecture that has persuaded its designers to clutch tightly to ideas rather than to share them. You might say the construction of a design is sharing it. It isn’t when you’ve lined your coat with something that can only be described as landscape make-up. The industry’s competitive nature has landscape architects auctioning forcibly diluted designs to the highest bidder. The business of landscape architecture has sacrificed futuristic exaggeration and profoundly fictional elements that PlastiCity FantastiCity values so highly.

“My God… What have we done?” The man dropped to his knees, which were shrouded by a thick greenish fog, unable to comprehend the thing that stood before him.

Despite what our panel of international judges thought, The Incredible Gammatectonic takes the unofficial cake (sponge with green icing in case you were curious) in the eyes of the editors but only just. It is set in the post-apocalyptic city of New York in 2100, which in turn is set in the absurd minds of Brian Hamilton and Camilla Rice. These two individuals are more concerned with telling a beautifully fictitious story than designing a forecourt for a giant hotel franchise. The Uncredible Gammatectonic narrates the ignorance and naive security what comes with living in a big city, and which almost leads to our species’ demise, were it not for blind, unaccountable luck. The unchanging standards within our profession are directly challenged, and very aggressively too. The Incredible Gammatectonic shows no hint of a plan, or section, or a formal scale, or any standardised conventions at all, because it doesn’t need them. It would be hindered with them. Without them, Hamilton and Rice have orchestrated a story about how an interstellar organism and a city in peril have been forced together to turn a stale, same city into something so much more exciting and invigorating. It informs us about how a future proposition could actually plug into the existing city. This competition submission extends an adaptive scenario; the supremacy of man beyond the limits of our reign. What would future cities be if our race didn’t possess enough control to influence them?

Thomas Hillier’s Potemkin City of Theatrical Delights understands that life is made up of fictional truths. Even a government planning report is compromised of future projections: it’s just fiction. By perceiving everything as fiction, his city knows that placing a “realistic” limitation on itself but a mental restriction. Landscape architecture is still defining itself. What a rare chance to help influence that identity. Why limit it to something of “reality” when it could be anything? Even a city built from forbidden love and Origami Lungs. It’s all fiction, and it all exists. The City of Theatrical Delights does more than disregard our industry’s ever shifting conventions and standards. It creates its own, far away from the world of AutoCAD, Green Corridors and drainage plans. All you Landscape Makeup Artists out there! Stop staining the city’s teeth with your green lipstick and do something with a little perspective and substance.

Once there lived a great Celestial Emperor and his Daughter, the Weaving Princess, who passed her days at her loom weaving the surrounding landscape for her father. Each day their world looked different because of her beautiful creations and she thought that there was no greater pleasure than the pleasure of weaving”

Because chances are that when we stand at the edge of our own self-destruction there won’t be any “crazy fungus” popping out at the drains to save us, nor will the sky turn black when a flock of winged friends come to our aid. We launched PlastiCity FantastiCity, completely unaware (and also rather confused) about how to nominate a winner.

The competition brief asked for something so personal and objective that in the minds of enough people, every city should have won. That says nothing more about landscape architecture than the importance of diversity in the face of sameness.

From the 17th Century until the early 1900s, the Middle American Agricultural landscape was consumed by sameness. It was bound by the inelastic Jeffersonian Grid; “the ideal networked production system for agrarianism”. The grids covered more surface than the American roads will cover in 2020. And in 1929, it was all destroyed. The repetitively rigid grid, “when exposed to small perturbations [redacted] as a mechanism of aggregation through which the initial onset on a perturbations [was] amplified to the point of collapse.” Sameness consumed this once living landscape until it was nothing more than a dust bowl plagued with dust storms reaching 1500 miles in size. For their own safety, those who once farmed the land quickly abandoned it. One man stayed.

“You are going to grow up to salvage this stiffening land,” whispered Rambunctious to his musty jars. He sat alone in his clapboard homestead, dedicating his remaining years to raising his Earth Skin Embryos.

His small plot of bare land hosted experimental earth skin embryos that hoped to combat the inelastic by-products of the Jeffersonian Grid. Perturbing low winds were amplified by the repetitive, rigid landscape to create massive dust storms that led to a point of collapse, Rambunctious dedicated his life and his earth skin embryos to salvaging the land, and protecting the future. He died in 1934, leaving behind notes, sketches and one musty jar. Rambunctious never saw his life’s work save the broken land, but that didn’t stop him from doing it anyway, and leaving it to be carried on. PlastiCity FantastiCity’s submissions are Earth Skin Embryos, young and almost unnoticeable now. But the ideas they leave will one day grow into developing cities, taking advantage of inelastic city fabrics before the sameness turns generates a massive, modern day dust storm.

Despite heavy use of words such as “hyper-escalate”, “growth” and “massive” do not think that PlastiCity FantastiCity is referring to scale. Do not think that scale is relevant. Do not even think that a city has to conform to roughly the size of London or Tokyo. Stelarc doesn’t. Internal architecture as a concept considers the body as an entire city, alone yet connected. Stelarc argues that the future city will be contained within the body, fragmentally, so to speak. “A person could see with the eyes of a body in one place, listen to what a body is hearing in another place whilst feeling an object an accessed remote arm from the body of a third place.” He goes even further to suggest that in the future cities will be entirely electronic; virtual realms that connect our senses and consciousness. These profound ideas confirm PlastiCity FantastiCity belief that without people, there is no city, and that a city can be the size of a pinhead if you want it to be.

“Instead of thinking of architecture as containing the body, perhaps it can be thought of as becoming a component of the body,” he explained, lifting his right sleeve to reveal an ear.

Stelarc operates on an entirely different part of the spectrum. His notions of robotics and virtually intelligent agents are hyper-escalated. He is presently working on a microbot of miniscule size, such that when it walks up his tongue and into his mouth he will have to concentrate hard not to swallow it.

If the city chose to swallow our practice, most likely due to an irritation at being suffocated by commercial propaganda, do you think it would like what it tasted.?

PlastiCity FantastiCity is the search for the future city. Our city has teeth because it is esoteric to think that a city could have teeth to begin with. It’s a thought that hyper-escalates a fictional realm, letting giant nocturnal toothbrushes out to play while mundane street cleaners aren’t bothered with them. PlastiCity FantastiCity wants to see landscape architects concerning themselves with more than where to put that tree, or what to build on the clad decking form. It wants to see ideas passed on and shared, deserted and found again. But more than anything, it wants to see you dealing with your city’s stress induced tongue ulcer. That is if your city has a tongue, of course.

Weird idea really… a city with a tongue. Take it if you like, like we said, it isn’t ours. But then again, you may never have seen it with teeth to begin with.

When we creep barefoot into the city at night we see giant mechanical toothbrushes.

What do you see?