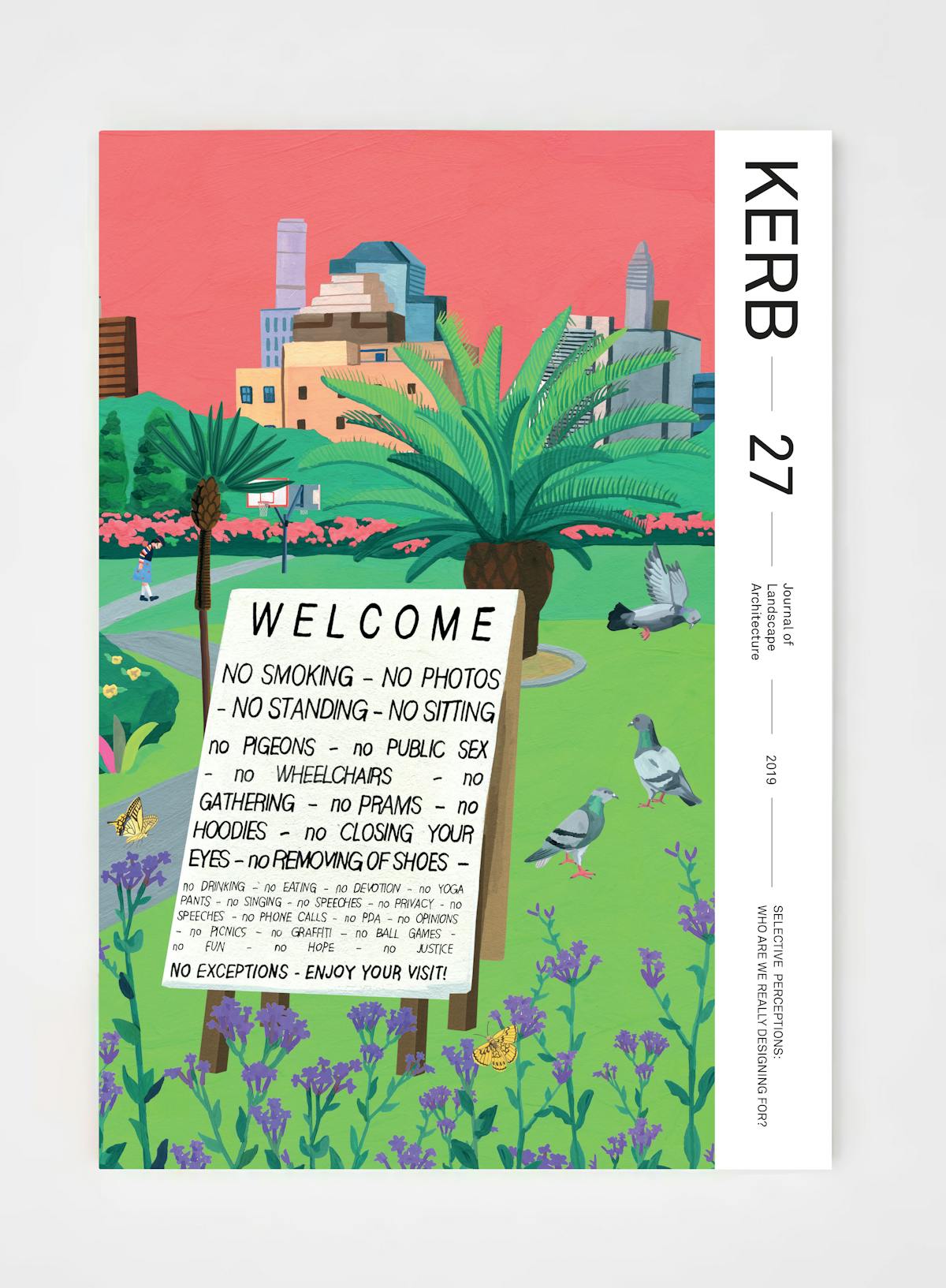

The spaces we inhabit in our daily lives have been designed for people, but have they been designed for you?

There is a swathe of agendas embedded in the design process. They are predicated on who is setting out the brief, where it is in space, the political climate at the time, and the desired uses. Often in these designs particular people are designed for, and others are designed out. Throughout the design process designers can be complicit in, oblivious to, or supportive of the political agendas of the client.

This issue of Kerb poses two critical questions: firstly, whose responsibility is it to make sure that public spaces are accessible to all, especially those who are marginalised? And secondly, what influence can and do designers have over these outcomes? This complexity and tension is realised in the diversity of submissions, and is key in particular contributions.

Who is included in a space, and how, is largely dependent on the tools the designer has in their toolkit. Beyond our drawing conventions, software, and pen case, there are tools we can use that are less tangible. In our interview with him, Walter Hood called for landscape architects to increase their social theory literacy. It is this literacy, he argues, that is the key to us making unique, sensitive and valued landscapes, but that we are severely lacking as a discipline. Danielle Toronyi’s submission walks a similar line. Her work helps to communicate the experiences of people with neurodivergent conditions in a city to designers of urban space. Toronyi’s visual representation of sensorial perceptions gives neurotypical people a sense of the experiences of someone with autism. Without these tools, designers are unable to generate sensitive and valued landscapes, or work against the often hegemonic campaigns by private developers.

The Forest City project in Malaysia is reclaiming tracts of seagrass beds to “develop” the land into housing for 700,000 residents. Among other things, the project’s master plan intends to protect the seagrass ecosystem that local fishermen rely on. Just who the residents will be is unclear, as the local Malaysian fishermen cannot afford to live in the development.

What is interesting here is the hierarchy of considerations in this project. Forest City sits within a wider context of neo- imperial, capitalist agendas, and the dichotomy between corporate master plans and the lived experience of people.

This dichotomy reveals itself time and time again. There are pertinent questions to ask, especially when considering who is involved and, more importantly, what is lost when marginalised voices are shut out of the conversation.

Brent Greene and Abigail Varney show us how inviting queer readings of a space can open the conceived range of a landscape, and can work to remedy even the arguably failed capitalist landscape of the Docklands, Melbourne. Further, a piece by Lois Nguyen argues that disabled experiences are being designed out of urban space by the focus on legally mandated disability access requirements. Further, she argues that in doing so we are missing out on a challenging and exciting design question – how to design for diversity in physical experience (beyond a designated slope gradient or handrails). Both works highlight to us the value of involving traditionally marginalised voices in our design process, not only to ensure inclusiveness, but also for the wider benefits this brings to our designs.

Greene and Varney present a version of queerness in space that while subversive, doesn’t portray acts of queerness in space to be dangerous acts. In contrast, Eloise Choquette presents a story where being queer in a public space was a life or liberty endangering act.

Ironically, it has not always been so easy to be radically different in public (space). Choquette’s work highlights the struggles of the people who sit on the fringes of society almost a century ago with the Caravan Club, a safe space for queer identifing people that was consistently on the verge of closure and under surveillance. Yet today we continue to speak about the need for safe spaces for the queer community and other marginalised groups. In their struggle, we can learn about the courage to take action. It is because of them that we can enjoy the (limited) freedom we have today, and can push the goalposts even further.

As designers, if we are pushing for change, it is not enough to only passively read and talk, we must be bold, make claims and take action. This issue of Kerb provides us with an opportunity to better learn about the people around us, and to consider new ways to think about our designs. Further, this edition contributes to a wider call for action. In the words of Choquette’s submission, ‘We must understand [design] from a different stance, as part of a wider, even more complex system. We cannot hope to change the way we design if we do not also work, continuously, to dismantle capitalism, racism and the patriarchy’.

Abstract

The exclusivity of urban assemblage has granted access to only a select few, and only in select ways.

Cities house some of the most diverse populations, while paradoxically, corporate buy-in has created an increasingly homogenous built environment. Design that does not consider the diversity of its community produces a narrow outcome, and decision makers are at risk of becoming increasingly abstracted from their constituents.

In effect, this deepens the exclusion of particular populations from our cities, and reproduces predetermined outcomes, based on narrow and biased perspectives. We all have the capacity and responsibility to contribute to, and be aware of, the world we are designing. Structural inequity promotes race- class- gender- age- ability- sexuality- based exclusion, whose effects multiply throughout society. How should and do designers address this context through their practise?

Design should be for the people, both the expected and the unexpected user. We should be empathetic, open and accountable. Does that really reflect how work is done or valued today? How are design professions responding to this tension, and what are the consequences if they don’t?

Contemporary society is approaching a reckoning of identity, to which designers will have to respond. Kerb #27 addresses issues of inequity in our built and social environments, and asks the question: Who are we really designing for?