‘We thrive in cities exactly because they are places of the unexpected, products of a complex order emerging over time’[^1]

Although public urban spaces are generally built to (and accepts as inevitable) exponentially faster rates of change. Alongside this, and for the first time in history, we are experiencing a new phenomenon: a greater percentage of people are living in urban conditions than in rural areas. This suggests our future cities must deal with a heightened ‘omniurban’ condition representing a fundamental shift in both the scale of the city and how we perceive its role(s). It also raises a number of complex questions about the relationship between design and public space: how its configuration and occupation can be responsive (customisation), how its lifespan deals with effects of speed and ongoing change (acceleration) and how it embeds the flows and forces of the future city (mobilisation).

Customisation

Our future cities will require us to further re-imagine and debate what constitutes public-ness and privateness. As technology and the media continue to overlap these conditions enabling people to be tracked, recorded and monitored in both public and private landscapes (be it through surveillance cameras in public space or through the GPS capabilities of mobile phones, etc) these binary separations of the city’s spaces will become increasingly meaningless. The control we have in our private environment iS becoming increasingly available in public space; listening to your iPod at the City Square or watching a movie on your mobile in the Carlton Gardens. This shifts perceptions of both the role of these spaces and the definition of their ‘public-ness’.

User-driven content in digital realms give individuals the opportunity to communicate instantaneously with each other and these informal, chatty personal exchanges are available to anyone accessing that web page. It is a new type of public space which plays on a particular (yet knowing and consensual) voyeurism and further diversifies conceptions of public and private space. This has spatial and programmatic ramifications when translated into the built public realm. Projects such as Federation Square have made initial gestures towards ‘user driven content’ with people being able to see their text message in LED lights on a building façade or watch themselves walk through the space on a screen. But how can the design of public space test and embed the notion of mass customisation and user driven content in a manner which in fact raises the potential to engage and respond to a wider range of ‘publics’?

Our cities are already entangled in these conditions of instantaneous mass communication, adaptability and responsiveness. Technological developments will effect our expectations of the city and its spaces. This has the potential to change how we design for the future public landscape as well as demanding a conceptual, temporal and material reconsideration of the lifespan of our designs opening up opportunities to design public sites to become more temporary and fluid.

Acceleration

Taking the attitude that our urban public spaces should be a reflection of the contemporary public and its occupation of the city, it is appropriate that some of the space-time compression that now surrounds us starts to be reflected in how public space is conceived, designed and fed back into the city’s ongoing reinvention. Rather than continuing to design for the long term, how can our processes of designing and occupying urban public spaces adapt to this condition of acceleration? Engaging and designing within this blur between ‘public’ and ‘private’ facilitates something more fluid and temporary to emerge.

Our future public spaces will be neither static nor autonomous entities but exist as a network of varying lifespans, cycles and flows.

Considering the operation of an urban public space in a way that aligns it with an expectation of responding to the ‘speed’ of popular culture suggests its design be approached as a series of iterations as opposed to static or fixed outcomes. This has connotations and potential for how we design/redesign our public spaces in terms of temporary shifting iterations as opposed to long term objects. It positions the role of the designer not as the all-masterful pattern maker, but rather the inventor of a strategic framework which unfolds through operations and particularities of the site. The role of the designer becomes one of understanding the site conditions then intervening and tweaking these conditions, movements and flows on the site and speculating on the outcome. Formal design becomes a short term ‘armature’ or host structure which connects to existing physical, spatial and temporal cycles and acts as a framework for ongoing changes and occupations.

While re-imagining the lifespan of these future public spaces, the perception of design is also called into question. The role of design is always, in some way, linked to control, yet cities are increasingly complex and plastic multiplicities. The future city is a fluid city, one which prioritises flow, transaction and interchange. This emphasis on fluidity suggests a city without the expectation of fixed hierarchies, a city of transits as opposed to places. Presumably the role of the designer will be that of understanding, manipulating and guiding these flows (at their various paces of acceleration) and testing how these spaces are utilised, occupied and configured.

Mobilisation

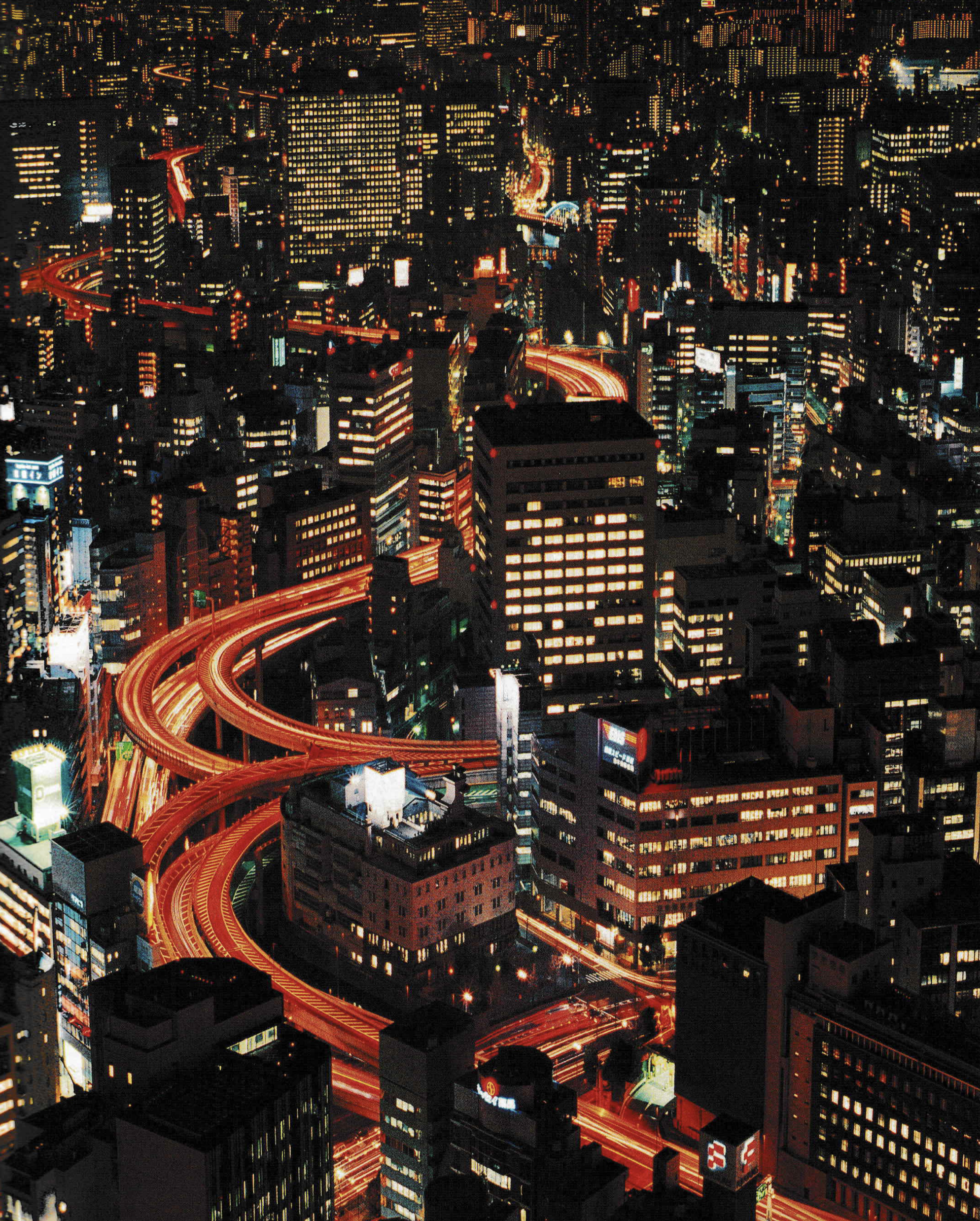

As our cities continue to reinvent themselves the way in which people, goods, information and capital move through them is shifting how ‘the urban condition’ is understood. Technology, decentralised information and global economics challenge the role of the city and our occupation of its public spaces; suggesting more direct engagement with the accelerating flux and rapid transformation of the urban condition. This changing connection with the public landscape results from speed, mobility and the sheer volume of these flows; enabling new ways to claim or territorialise the public spaces we inhabit.

Considering public space as transits suggests the reimagining of both the role that the city’s physical arteries of roads, laneways, train and tram lines and bike paths play as well as how this notion of flux and movement can become embedded in the formal and traditional conception of public space. It enables a new way of understanding the city as a network which is ordered by designing through ‘flows’ as opposed to objects: flows of information, communication, people and time. Can public space become a more active flow’ in the future city?

In our future cities it is this relationship between movement, time and space which will most effect the changes that occur in how are cities are inhabited. Already the traditional concept of the city with its assumptions of centre and periphery being embedded within its physical structure; its boundaries assuming a corporeal scale, and its distances being measured in empirical time is being challenged. Urban public space is the threshold where the changes in how we understand and engage with city are tested. For this reason the role of public space in the future city should be that of a microcosm that redefines the possibilities of the city. Technology, car-based mobility and the resultant sprawl have dramatically affected our sense of the relationship between time and space, changing how we understand the condition of the urban fabric and suggesting a design process where the outcome is constantly evolving -and does not necessarily expect to be left in the same state as it was found.