Models, both those formally acknowledged and named, and those that are tucked neatly into the hidden pockets of our everyday beliefs, are pervasive. They inform much of what we think about things and thus how we operate in, and on, our worlds. If we are to achieve change (as designers attempt to do) we usually model what exists in some way. Perhaps we model the site and social conditions where our work is to be centred. Then, in a broad sense, we establish a model of our intended interventions in what we modelled as extant. We also model how our proposal will work, what variations will come about and how our design will develop over time. (In current speech we claim to ‘test’ the design.) The senses of the term ‘model’, as used above, differ; they include physical, social (possibly modelled through descriptive words) and maybe numerical models of patterns of use and change. What I wish to explore here is philosopher Max Black’s evocative description of models as ‘speculative instruments’.1

For the purposes of this paper I will assume that the editor’s fear, encapsulated in the call for papers, concerns stagnation rather than complete loss of vital signs in the discipline of landscape architecture. On this basis it is reasonable to ask what sort of speculative instruments landscape architecture needs and how it could use them in the pursuit of a livelier future. My contention is that better attention to models and their explorative use might jolt designers from conventional patterns of operation and lead to potential reinvigoration. There is no intention on my part to make the case for a particular type of model or a particular way of using modelling tools. I do report, however, on a studio in which computer models and physical models were both used in designing.

Models are devices that enable enquiry in any field, be they mathematical, statistical, verbal, digital or physical. In designing they have often served a number of functions. An array of model types supports speculation in designing. This is an inherently speculative note on the value and use of models, drawing on my personal efforts to use models to inquire into possibilities. The paper progresses through a set of five assertions.

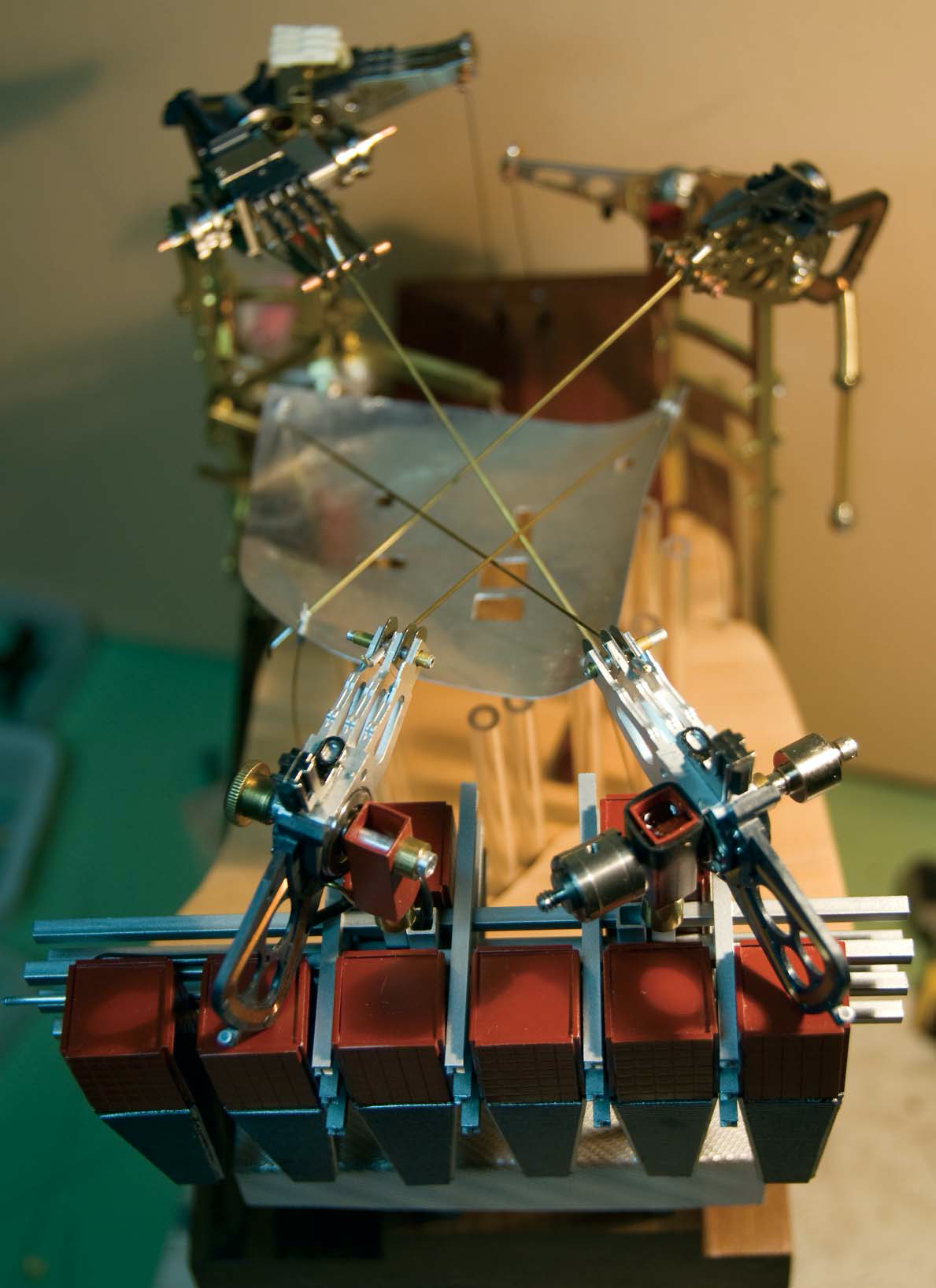

Image courtesy of Peter Downton

Assertion 1

The differences between explanatory models and instrumental models need to be clearly understood and respected.

Elaboration: If, say, we are to think about cities, areas within them, or sites and their surrounds, there are various models of their structure. In a recent book on models, there is a paper that starts by evaluating two models for the structure of a city by drawing from Alexander’s famous 1965 paper which contrasts the tree and the semilattice.2 Elsewhere in the same publication, there is an argument for the more fashionable ideas of networks and emergent bottom-up processes.3 Such models are intended to explain, and the explanations they provide then shape the directions in which designers search for appropriate interventions. Some designers presumably make assumptions (hidden or unexamined) about the way the perceived elements of an area of interest relate to one another – others cannot tell as nothing is explicitly stated. The model chosen creates and explains an array of things and assorted phenomena will be seen to fit this explanatory model. Since there are no facts without enshrouding theories, what is deemed to be ‘hard data’ about an area will almost certainly conform to the expectations of the modelling, because it will be sought and viewed through the lenses of that model.4 The observed data will thus serve to confirm the explanatory correctness of the model. I suspect that this is unavoidable; even the attempt to be free of any shaping model implies a model – one that describes a non-ecological state in which nothing is related to anything else, or of any more (or less) importance than anything else.

Instrumental models allow something to be done, in this case designed, rather than explained or represented. Instrumental models look forward; their domain is what will be, not what was or what is. To assume that a sound explanatory model can be extended as a model for a course of action and exploration does not necessarily make sense – there may be potential for this, but clear evaluation is necessary. Models facilitating agency are necessary for designers. Enthusiasms for generative systems, such as those employing scripting, do not allow the machine to become the agent. The designer does not abdicate responsibility – agency is simply buried earlier in the process where the decisions are less open to scrutiny.

Assertion 2

To operate effectively designers must distinguish the types of instrumental models they employ and then examine them to evaluate their strengths, weaknesses and appropriate use.

Elaboration: This discussion is confined to three types of models used by designers: descriptive, generative and representational. Designers compound various things, all called models. For the moment, in an effort to be clear, consider only straightforward physical models constructed of card, balsa, perhaps some wire and one or two other materials. Typically there might be a site model. This is descriptive. This might be hacked about, added to and generally messed with as part of designing. Possibly a number of new quick models might be made. Their function is the same in each case; they are about generating and testing ideas. They start to shade into the next class of model in that they represent these ideas and proposals to both the designer and to others – typically others in a design team – as the design is being developed. ‘Pure’ representational models are those with the primary function of showing clients and communities of interest what the (final) proposal is like. They represent the outcomes of the decisions taken. Although, sometimes, late modifications may be made on the basis of others’ critiques of a representational model, the intention underlying their making is to show off a completed design. Admitting that there is slippage between these three model types does not invalidate the distinctions between them; these centre on the intent with which they are made. Of principle interest below are the generative models used to speculate and to evaluate ideas while designing.

It seems common to almost ignore generative models in much of the discussion about models and to concentrate on representational models, often offering an art criticism-based account of their functioning where the visual is a privileged king while most other senses are reduced to paupers and hapticity is totally forgotten.5

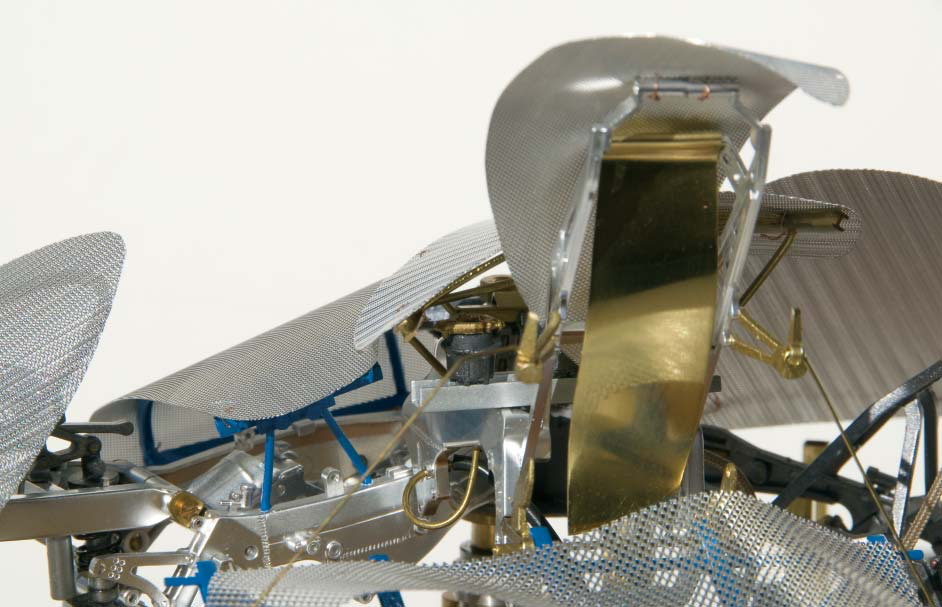

Image courtesy of Peter Downton

Assertion 3

For designers, any model (in the sense of an exemplar) is a means for conveying embodied design knowledge.

Elaboration: A term such as a ‘model child’, or the way the word model is used in fashion, are clear examples of a model being used as an exemplar something to be emulated, celebrated, or copied.

In design areas, strict copying is frowned upon, but heavy borrowing of ideas, approaches and formal ploys is constant and quickly leads to styles and fashions in designing. Models of proposed designs and constructed projects function in the same manner if considered as exemplars. They show others what was designed. They can be interrogated by designers and other people and in this process trigger new knowing by those trying to understand what was done and why. In this sense any completed design embodies knowledge and the potential for knowing when it can be accessed by others as a model or a fully realised entity. It is a mechanism for learning.6 The term model can be extended here, as it once was, to also mean drawings or more recently computer renderings.7 Likewise, I include photos of projects as operating representationally in a similar manner to a model and standing for the real thing.

Assertion 4

Designing with a 3-D model (be that physical or digital) enables a speculative process that offers more than is available by designing first and then making a representational model for testing or communicating.

Elaboration: The claim here is that the most inventive way of working is to avoid (or minimise) designing first in 2-D (whether on paper or a screen) prior to subsequently producing a 3-D model of the designed outcome.8 Having said this, the reality is that drawing in a notebook is portable and quick; modelling is not often either. For many designers some sketching will precede anything else. For a skilled designer, three dimensions, the fall of light, the passage of time – any of an array of concerns – can be noted and indicated to herself. It can then be subsequently mocked-up in 3-D for further work. Whether done on paper, a screen or the modelling bench, the significant part of this generative process is the conversation conducted by the designer(s) with the material of the design as it is emerging. The more the conversation is between the designer and a 3-D self-informing representation the more evocative and informative the process. Demonstration is privileged over representation; the conversation is richer.

Starting in 3-D is not common. Continuing to design entirely in 3-D is rare in design offices judging by my formal and informal surveys. I have made a practice of building physical models as part of designing.9 My hand-made analogue models work in the same manner as any rough design model in that they are tools for exploration and discovery. Although their development places them firmly in the category of generative models, in the end they become representational models. There has never been any intention to build these small pavilions at 1:1 scale, although, with appropriate engineering and detailing this would be possible. They have been vehicles for discovering about issues in designing. In this sense they are not models of intended future constructions. They are representing themselves. As they are models, in the sense of small objects, they are model models; they are their own ends and serve as works in their own right. To emphasise this I make them with care, a degree of polish and a rich palette of materials.

With the aid of ARC Discovery Grant funding a number of researchers centred on RMIT University have been studying the roles and uses of models in designing – the Homo Faber research project.10 We have sought to discover how designers (undergraduates, postgraduates and offices) use models in their designing, and we paid particular attention to the ways their use is changing, particularly in evolving new ways of working. The last few years have seen a substantial shift in the ease with which digital models can be built in a computer and outputted through a digitally controlled machine. It is not necessarily clear what is gained and lost from a design perspective. Speed of delivery is cited as a major advantage; some do not believe that quality is enhanced. An extension of the discussion above highlighting the confusion in the purposes and uses of models may offer insight into these issues. An increase in speed leads to a reduction in reflection and exploration, but digital means also allow different kinds of exploration.

Assertion 5

Working interactively in parallel between the digital and the physical produces the beginnings of a modelling hybridity potentially offering advantages for speculative idea generation.

Elaboration: As part of the Homo Faber research project, a number of undergraduate studios have been conducted. In one of these, twenty-five interior design and landscape architecture students worked together and two architecture students joined the fun.11 The studio projects variously required people to use either computer modelling techniques – mostly working in Rhino – or physical modelling. For some projects there was an expectation of swapping between modelling means involving starting in one method and changing part way through. Designing entirely through modelling was advocated, although most people sketched first for most of their projects.

In the final project, which required team designing and making (in pairs except for one trio), the predominant mode of operation by the groups involved frequently exchanging between the digital and the physical. People became increasingly confident in their abilities to work in whichever means seemed to offer the most useful way of generating and resolving ideas. Interestingly this grew quite rapidly, particularly given that the pairs were formed by people from different disciplines who did not have a background of working together. They had to explore their different knowledge bases, styles and skills, find a common mode of working, and establish an approach to a very open-ended assignment which was set up to require them to create a story, choose a site and establish their own detailed brief – they had to find techniques for designing when they did not know what they were designing. Their level of speculation was thus heightened. Admittedly there was a rather low level of reality along with pragmatic constraints to spoil speculation in this project, but the mechanisms of operating appeared to enhance speculation compared to other ways of operating. Presentation was through models employing laser cutting, dust printing, paper cutting – any digitally controlled method or combination of methods.

Sketch models of fledgling design ideas were made in paper, card, sticks and plasticine by some, and in Rhino by others. More detailed exploration or resolution was just as likely to involve a swap of means. Designs also progressed employing the two means in parallel, with teams exploring both kinds of modelling at once – perhaps one team member working one way, while the other used the other method, but also through developing alternatives or aspects in the different ways at more or less the same time.

It was also notable that many design offices, responding to a subsequent survey for the research project, advocated various versions of working across the two modelling means. For many of them, physical models remained important as generative and testing devices although they are being increasingly restricted in their use because they are comparatively slow and therefore expensive.

Conclusion

Models are potent; awareness of their use, attention to their type, and their application as 3-D generative tools, rather than as representational devices, should enliven designing as an investigatory and speculative process.

Footnotes

-

Philosopher Max Black’s book, Models and metaphors: studies in language and philosophy, Cornell University Press, Ithaca, New York, 1962, is the seminal text on all aspects of models. He introduces the term ‘speculative instruments’ on page 237. ↩

-

Christopher Alexander’s output in the 1960s included Community and privacy: toward a new architecture of humanism (with Serge Chermayeff), Notes on the synthesis of form, ‘The city is not a tree’ and ‘Cities as mechanisms for sustaining human contact’. For those, like me, who were architecture students in the 1960s, Alexander opened up the whole idea of conscious modelling of urban and architectural problems as opposed to simply designing with no objective attention to such possibilities. ↩

-

The two papers are: Jonathon D. Solomon, ‘Seeing the city for the trees’, in Emily Abruzzo, Eric Ellington and Jonathon D. Solomon, eds, Models, New York: 306090 Books Inc, 2007, 174-184; and Helene Furján, ‘Cities of complexity’, ibid, 52-61. ↩

-

Here I am following the arguments put by Karl Popper in: The logic of scientific discovery, London: Hutchinson, 1959 (original, 1934); Conjectures and refutations: the growth of scientific knowledge, London, Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1963; and Objective knowledge: an evolutionary approach, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1972. ↩

-

Martin Jay, in his book Downcast eyes: the denigration of vision in twentiethcentury French thought, Berkeley, University of California Press, 1993, gives a wide-ranging discussion of this; and Steven Holl, Questions of perception: phenomenology and architecture, 2nd edition, San Francisco, CA, William Stout, 2006, offers designed examples drawing on phenomenological concerns. This book also contains pertinent essays by Juhani Pallasmaa and Alberto Pérez-Gómez. Juhani Pallasmaa also gives rich accounts of broader-based designing in The eyes of the skin: architecture and the senses, Chichester, England, John Wiley and Sons, 2005. ↩

-

This is argued in chapters 6 and 7 of a book which grew from my modelling in an effort to understand more about designing –Design research, Melbourne, RMIT University Press, 2003. ↩

-

This old use, from late in the sixteenth century, can be found in various places including citations in the Oxford English Dictionary. ↩

-

Although the term 3-D is widely used for computer-based models, I am not convinced these models are as 3-D as something that can be worked on in the hand. Such models are a species of simulated 3-D (sometimes termed 2.5-D). Clearly they operate in a differing fashion to either a 2-D drawing or an analogue model in the hand and have useful attributes not replicated by the other two forms. ↩

-

The first ten of the thirteen models so far built in this series are described, discussed and examined in Studies in design research: ten epistemological pavilions, Melbourne, RMIT University Press, 2004. The subsequent trio are at least partially elaborated in the second and third Homo Faber catalogues. ↩

-

This ARC Discovery Grant has had three exhibitions at the Melbourne Museum, and published catalogues and books, all under the title ‘Homo Faber’ with various subtitles. The project funded was titled Spatial knowledge and the built environment: the design implications of making, processing and digitally prototyping architectural models. The Chief Investigators are Prof. Mark Burry, Prof. Peter Downton, Associate Prof. Andrea Mina from RMIT University, and Prof. Michael Ostwald from the University of Newcastle. It has been managed and made to happen by Alison Fairley. ↩

-

The studio described was titled ‘Thrashing the machines’ and was conducted by Andrea Mina, Alison Fairley, Peter Downton and Juliette Peers ↩